Dan Lieberman's Exercised review

What CHIMP STRENGTH, hunter gatherers, and a boatload of peer reviewed studies tell us about exercise

This is the big one - 2700 pages in my e-reader, and I had more than a hundred bookmarks.

And what do you get for all those pages? It manages to be that rare mix of wide-ranging, in-depth, and entertaining. It covers everything from the molecular dynamics of metabolism to MMA cage fights and hunter gatherer lifestyles and health.

Why should you read this book or review?

Well, if you’re here, you’re probably in some vague cluster of “high human capital people working in tech, finance or AI,” and you’re probably rationalist, post-rat, or adjacent. A nerd, in other words.

And being a nerd is great, it’s definitely the done thing and a path to success and whatever nowadays. I’m a nerd myself. But I’m also a jock. A jerd? A nock? A jerk? Well, probably.

If you’re not exercising now, I hope this review or book can convince you to start.

If you do cardio but not weights, I hope to convince you that weights are worth it.

If you do weights but not cardio, I hope to convince you cardio is worth it.

If you’re not doing HIIT, I hope to explain what it is, and convince you it’s worth it.

And who is Daniel Lieberman, for that matter? He really tries to portray himself throughout the book as an “aw shucks” regular guy who’s basically an amateur when it comes to fitness and who’s just happened upon some interesting observations about exercise.

But of course, he’s an impressive human being. A Harvard scientist who studies everything from metabolics to kinesthetics, physiology to anthropology, who literally wrote the (Nature) papers on hominid persistence running, human barefoot running, and much else.1 He studies baboons, he studies the Hadza - a hunter gatherer population in Tanzania - he runs marathons against horses, he is one of the most respected academic advocates of barefoot running, he has a standoff against a hyena in the book, and much else. He’s somebody you should be willing to listen to, in other words, when it comes to “exercise as a general field of inquiry.”

And I’ll spare you the suspense: exercise is good, you should definitely do it.

That’s a wrap! There, see, we didn’t need to read a 2700 page book after all! I hope my review has helped you. Godspeed and good night, everyone.

Oh wait, you’re still here? Ok, well if you want some of the details and anecdotes and fun factoids, I guess I can say more.

So okay, exercise is good. But exactly how good is it?

What if I told you it can drive a 4x all cause mortality difference?2

What if I told you it can largely prevent or ameliorate all the diseases in the following list?

These are the “diseases of civilization,” or mismatch diseases. So called, because hunter gatherers, who are 5x more active and eat 5x more fiber than sedentary Westerners, don’t get any of these diseases. They are purely an artifact of a modern sedentary lifestyle and diet.

But of course, merely quartering your chance of death from any cause isn’t enough to get people to exercise - that would be silly! Only vanity is a strong enough force, and alas, the median person doesn’t exercise hard enough, or calorie count rigorously enough, to be able to lose weight, which we’ll briefly touch on later.

This is because we have evolved over millions of years to be as inactive as possible.

You can only use the calories you take in for 1 of 5 things:

Growth

Maintenance

Storage

Activity

Reproduction

Our bodies were literally evolved to spend enough but not too much on everything except reproduction, including the “Activity” bucket. Historically, this wasn’t a problem - as hunter gatherers, if you want to eat, you need to go to where the food is, hunt or gather it, and bring it back. Every day! It is only in our debased modern age where Grubhub and Instacart lie in wait to bring you an impossible global array of delicious prepared foods and groceries right to our doors with no more than a few finger taps.3

To really understand how our bodies work, we need to understand what was going on with our ancestors. If we look at chimpanzees, the average Hadza4 woman spends 115k more calories per year moving around and doing stuff than a similar sized chimpanzee. In other words, chimpanzees are considerably lazier than us. This is important, because it implies we explicitly evolved to be more energetic and try harder.

Indeed, chimps have it easier in two ways - not only are they more sedentary, they’re not penalized for that laziness. Great apes in zoos (chimps, gorillas, and orangutans) are 20-50% larger than their wild counterparts. “Of course,” you think, “those little guys are just like us, they probably just loll around watching the chimp equivalent of Netflix waiting for the zookeeper to bring them bananas.”5

And you’d be right! You’ve got the overall vibe down perfectly. They’re less physically active and get more regular food supplies, so they’re more or less just like us sedentary moderns, and that’s why they’re bigger than wild great apes. But they don’t get fat! They put those extra calories to use in making more fat free mass, and in growing larger organs, not to fat. A zoo chimp still maintains ~10% body fat.

Humans in the same situation get fat, as we have famously observed in Western society for the past hundred years. Why is this?

Essentially, we left an easier ecological niche, where you hang out and eat fruit and plants and whatever food is around you every day, to foray out into the savannah, where we learned to walk upright, got much bigger brains, and underwent various other adaptions that differentiate us from chimps. Including the inclination to put on more body fat in a calorie surplus - food was spottier and less dependable in the savannah, and having a reserve of body fat was correspondingly more important.

So our ancestral legacy has cursed us two ways - first, we must be considerably more active than our great ape ancestors, every single day. Second, we get fat in calorie surplus, instead of just packing on more muscles and bigger livers. Worse, the fact that we had to be more active than chimps for several million years means that our body built a bunch of repair and maintenance systems keyed on physical activity, such that if we are NOT active, we become susceptible to many and varied ways of breaking down, ie all the diseases of civilization.

Which brings us to the REAL villain in this story - chairs.

Okay, it’s not chairs, it’s sitting. Although Lieberman is very explicit about eschewing the “sitting is the new smoking” meme, this is in hilarious contrast to him unloading study after study after study on why it’s basically the new smoking. Actually, it’s arguably quite a bit WORSE than smoking - smoking only had a hazard ratio of 2.8 versus non-smokers once controlled for other variables, whereas exercisers vs sedentaries have a 3-4!

“In a nutshell, persistent physical inactivity along with smoking and excess body fat are the biggest three factors that influence the likelihood and duration of the major illnesses that kill most people who live in industrial, westernized contexts.”

I mean, that sounds like “sitting is the new smoking” to ME, but what do I know?

The total time Americans spend sitting has increased 43% between 1965 and 2009. I could show you a graph of obesity rates and / or “diseases of civilization” rates increasing a lot in that specific time window, but why bother? I’m sure you believe that’s probably true.

You want a nice one-table takeaway? Consult the following table:

If you can bring your numbers6 (whatever they may be) from closer to the “modern sedentary” column to the Hadza column, you’ll age a lot better, be a lot healthier, and eliminate or greatly reduce your chances of getting the various diseases of civilization.7

Why is sitting so bad for you? Well, your body was forged in an environment where you needed to be as active as people in the Hadza column up there, and when you’re not, your body sets itself on fire in protest. Kind of.

Chronic inflammation stems from inactivity and excess organ fat.

In a Danish study, researchers paid men to take no more than 1500 steps for 2 weeks. In just two weeks, they added 7% more organ fat, and began exhibiting signs of chronic inflammation, and had impaired ability to reduce blood sugar after a meal. That’s only TWO WEEKS.8

Sitting slows the rate we take up fats and sugars in the bloodstream, and whatever isn’t taken up will turn into fat. Sitting is usually accompanied by psychosocial stress,9 and that stress increases cortisol and makes you pack on organ fat. Another way it increases inflammation is that when we move our muscles, they release myokine messenger proteins that influence metabolism, circulation, bones, and inflammation. But if you’re sitting, you’re not moving your muscles, and not producing these myokines.

What can you do if you want those nice 4x all cause mortality benefits?

Get a standing desk - you’ll burn 8 calories more per hour. Better, get a treadmill desk.10 If you can’t do either of those (or even if you can), then fidget. Fidget like your life depends on it!

In metabolic studies, fidgeters burn between 100-800 calories more per day vs those who sit more inertly, and fidgeters have a 30% lower all cause mortality after adjusting for exercise, smoking, diet, and alcohol.11

But most of all, what you can do to get those mortality benefits is exercise, of course.

Which brings us to exercise! Always my favorite topic, and why we picked this book up to begin with.

Before digging into running, speed, and endurance vs sprint tradeoffs, I’d like to first divert into a topic near and dear to my own heart: strength.

Resistance training, otherwise known as strength training, is part of “exercise” in terms of what’s recommended for better health and aging. There’s usually a divide between “strength” and “cardio” people - the meatheads who can bench 3 plates on average hate cardio, the marathon runners who excel at cardio look askance at the meatheads, and never the twain shall meet. Lieberman, it should be noted, is definitely in the second camp - he runs marathons regularly, but has always struggled with lifting weights.

But before we get into what you should do on this front (train comprehensive resistance exercises 2-3x a week, basically), why don’t we look at our evolutionary ancestors again? That’s right, I’m talking about CHIMP STRENGTH.

Chimp strength is a fun topic, because it has a lot of misconceptions and urban legends around it. Chimps are supposedly many times stronger than even 2x larger humans, and could toss you around with abandon, and if you were foolish enough to enter an arm-wrestling contest with one, he would probably rip your arm clear out the socket and whack it back and forth on the table a couple of times, winning by “technical force majeure.” It’s all false.

The studies indicating chimps are massively (5-8) times stronger used a handful of dynanometer pulls in the 20's from a single chimp, then scaled the weights pulled to the chimp's size to arrive at the amount chimps are stronger than humans.12

Those studies were actually refuted 40 years later, and more recent studies by Umberger and O'Neill13 have indicated that chimps are really only ~1.35 - 1.5 times stronger than humans. Several other studies (Liebermann cites no less than 5) triangulates chimpanzee strength at about 30% higher than human strength.

That’s tiny! Any random person who goes to the gym and weight trains regularly is 30% stronger than the average person, and so has attained the magisterially intimidating rank of CHIMP STRENGTH. If that doesn’t incentivize you to get into the gym, I don’t know what will.

The real reason you shouldn’t get into a fight with a chimp, of course, is because they have very long canines, 3-4x stronger bite strength than dogs, and biting as one of their first-pass aggression methods. But you know, feel free to pick up the gauntlet at a chimp arm-wrestling match if the situation is set up in a safe way.

But if you want something ACTUALLY impressive strength-wise in our ancestry, look no farther than Neanderthals.

Neanderthals really WERE intimidatingly strong and buff. The average male Neanderthal would be something like 5’ 5” and 80kg (176 lbs), at 10% body fat. There are specimens that were 5’ 9” and probably 95-100kg (220 lbs), who were probably also 10% body fat. That’s competitive bodybuilder territory, and they didn’t get that big by doing 5 sets of 10 in a gym, they got there by literally hunting mammoths with spears and such.

Male Hadza at 5’ 5” are ~45-55kg (100-120 lbs) - the Neanderthal has 25-35kg of mass on them, and could probably toss them around like a toy in a wrestling match. In addition to having a lot of extra muscle, it’s very likely Neanderthals had higher testosterone too. And by “higher,” if you scale from facial width differences, the *average* Neanderthal male would have a 1-in-ten-thousand H. Sap testosterone level - far, far out on the end of the bell curve. So they’d get a strength buff from their extra muscle mass directly, and an additional buff from much higher free testosterone.

I would interject here about the fun dynamics around how our immediate progenitor species, the common ancestor of the absolute unit Neanderthals and us, was essentially the same thing (an absolute unit). Huge muscles, testosterone up to here, twice as sexually dimorphic as us, essentially the Andrew Tate-ian superman. Also, hugely more reactively aggressive.

And yet, it was us cooperating beta bugmen - H. Sap - puny, gracile, self-domesticated, not reactively aggressive at all - who ended up dominating and wiping out Neanderthals and literally every other confrère hominin species alive at the time, when culturally modern Homo Sap of 50-60kya did a final outmigration from Africa. The impossibly strong, ripped adonises never stood a chance. 😂

More to come in that vein in my post on how we stopped bullies and inadvertently created a world dominating super weapon.

But as a mere human, what if you want to get strong, so that you’re not shamed at the beach by a rogue chimpanzee kicking sand at you and then stealing your girlfriend?

This was a great interest of mine for many years,14 but it boils down to a simple three point recipe:

No pain no gain - do squat, deadlift, and bench for 10 reps for 3-5 sets at a challenging weight (ie 8 / 10 effort level on the final reps)

Do either more sets, more weight, or both at your next session, and do 2-3 sessions a week (progressive overload)

Sleep and eat well between sessions

Lieberman actually gives far more generic advice (“do eccentric and isometric exercises”), but by his own admission he is not much of a lifter, has always hated and struggled with it, and is merely channeling officially recommended standards from the College of Sports Medicine.

So do the three point list I put up there - I was a regionally competitive strength athlete for several years and have read every book Renaissance Periodization has published, and it’s basically the maximally compressed recipe for getting strong or swole.

Why should you care? If you’re currently doing cardio regularly, why commit the extra time to lift weights?

Well first, being strong and looking good is its own reward. Being in a place where daily activities are easier, where you can grab and carry that extra couple of bags of groceries without struggling, where you can carry a luggage up or down some stairs gracefully and easily, is an end itself.

Also, if you’re a guy, who do you think is going to be more respected by women - the guy who struggles to carry a few bags of groceries, or the guy who grabs her big luggage and zips it up or down the stairs for her with effortless elan?

But that aside. There are actual health benefits to doing weight training. Broadly, you eliminate or greatly ameliorate sarcopenia,15 and osteoporosis.16 In other words, you’re going to age much better, and retain more capabilities as you age, in addition to looking better and being stronger in daily life.

After all, our chief authority here, who is a self-confessed weight-training-phobe, thinks it’s valuable enough that he actually does resistance training.

And what does the good doctor himself do for resistance training? Lieberman “developed a gym-free routine doing push-ups, squats, and a few other exercises in the privacy of my own home.”

If you’re a newbie to weight training, there’s a good chance you can get away with only lifting 10-20 minutes a week, as I go over in my review about super slow strength training here.

Let’s talk about cardio now. Specifically, let’s talk about running.

Lieberman literally wrote the Nature paper on persistence running17 with H Erectus having a nuchal ligament, Achilles tendons, an arch spring,18 and the other elements of the package. Lieberman is a big fan of running - he does the Mingus Mountain “man vs horse race,” in Prescott, Arizona running a marathon against horses, and beating 40 / 53 horses to the finish line. He also owns up to being partly responsible for the barefoot running trend, regarding which he wrote the foundational “Born to Run” Nature paper.

You can tell running is something he’s thought a lot about and extensively studied the mechanics of as you read the book, and not just in humans, in multiple species.

When you walk, your legs act as pendulums, storing and releasing gravitational energy and minimizing the energy you spend. Walking takes about 50 calories a mile. When you run, you’re literally jumping using one leg, over and over. It uses ~100 calories a mile.

A dog or a horse has 4 legs they can push against the ground to make power - we have ONE when running. It’s like a one cylinder engine vs a 4 cylinder. Our ape ancestors also gave us fat legs and ankles and big feet - ostriches can run 45mph in part because they have much less mass in their legs and feet and can move them more efficiently at the hips.

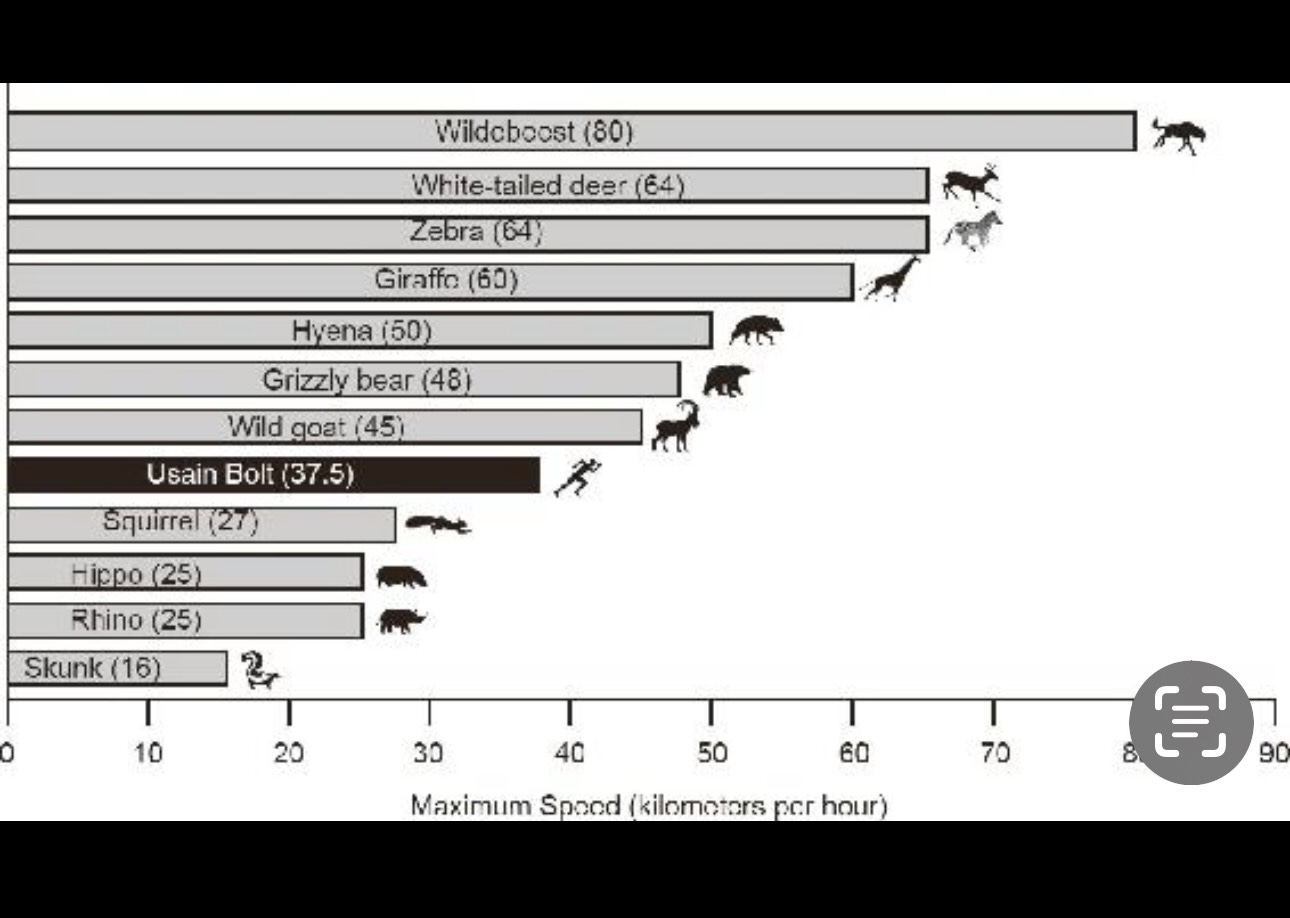

So compared to other animals, we are slow. Not just “slow,” but like slooooooowwww.

He talks about Usain Bolt quite a bit in the book - which makes sense, because he’s the reference class for “fastest human.” Which, to put it in American terms, is ~23mph.

Speed is equal to stride length * rate. Usain Bolt is faster than everyone else because he’s tall and has long legs, but he moves them about as fast as his shorter competitors. This takes immense strength. In the brief interval his feet are in contact with the ground as he’s driving himself up and forward, he has to exert a LOT of force to keep his greater weight moving as fast as his competitors.

So basically, if you want to be faster, get strong, so you can move your legs at a faster rate.

But overall, if you want to be fast, bipedalism was a mistake. It made us clumsy in trees, prone to tripping and falling, more vulnerable to lower back pain, gave us riskier pregnancies and more difficult childbirths, AND made us slow. But you know, we have the internet and chip fabs and jumbo jets, so it’s not all downsides.

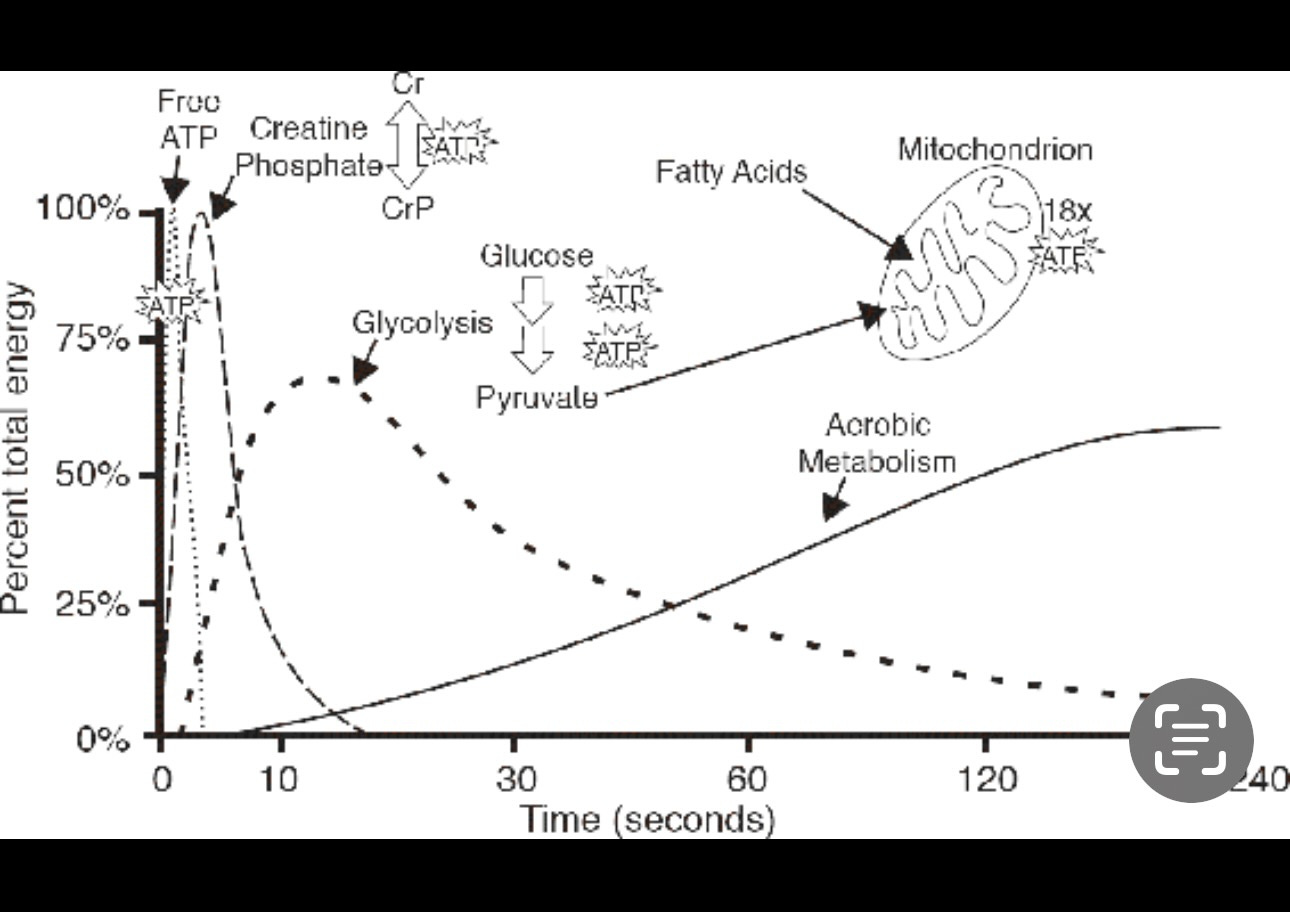

All “speed” happens in that first ~20-30 seconds. You can sprint all-out for that long, but after that your energy reserves are exhausted, and you’re going to sharply slow down as you switch to glycolysis and then to aerobic metabolism, each of which are longer metabolic chains and processes involving more steps, so which reduce your total power output.

For anyone who’s actually trained seriously or competed, you generally know whether you’re a “power” or “endurance” athlete. This comes down largely to the types of muscle fibers you have - sprinters have 70% fast twitch fibers,19 marathoners have 70% slow twitch fibers.20

If you have a bunch of fast twitch fibers, you’re a good candidate for “power” sports like sprinting, 100m dash, shotput, olympic lifting, and power lifting.

If you have a lot of slow twitch, you’re going to do great at marathons, tour de France, triathlons, or similar endurance competitions.

He even gives a nice breakdown of what percent various running distances are aerobic:

But one thing that I like in the book, is that he challenges whether there really is a speed vs endurance tradeoff. The fastest marathoners finish in a little over 2 hours, which is a 4:40 pace for 26.2 miles straight. Most regular people can’t run a single mile at 4:40 pace.

“Compared with 99 percent of humanity, these marathoners evince no tradeoff between speed and endurance. Instead, they are evidence that you can run both fast and far.”

In fact, there seems to be a “general factor of athleticism,” much like “g,” but you know, for jocks instead of nerds. Let’s call it “a.” Decathletes who do better at 100m dash and shotput also do better at the 1500m run. Even in individual frogs, snakes, lizards, and salamanders, the ones that produce the most rapid bursts of power also have the most endurance. Hunter gatherers are good at endurance, but also reach 12-17mph sprint speeds.

How can you be good at both speed and endurance, or to put it another way, how can we train to increase “a?”

For a more in-depth view, I’ll direct you to my reviews on endurance and for becoming triathlon fit. But the quick answer is HIIT.

HIIT.

Lieberman essentially recommends getting good at endurance, then doing HIIT (High Intensity Interval Training). HIIT is the very best training anyone can do.

What if I told you there was a type of exercise that took 1/3 to 1/5 the time of a regular cardio session, AND it was more fun and intense, but it had the benefits of a full 40-60 minutes of cardio, and then even MORE benefits on top of that, to race performance, strength, anaerobic fitness, explosive power, and many other things?21

Where’s the downside, right?

I mean, the basic theory behind HIIT is “take all the distributed, moderate effort you would have exerted over that 1 hour cardio session, and cram it down into a maximum-effort 4-8 minutes.”

It sounds like a great trade? I’d definitely take less than 10 minutes of max throttle intensity over an hour of moderate trudging?

HIIT allows you to recruit more muscle fibers, and more efficiently, it increases their size, it makes your heart chambers larger and more elastic, improves the size and elasticity of your arteries, increases the number of capillaries, improves muscles’ ability to transport glucose, increases the number of mitochondria, lowers blood pressure, and also rotates your tires and does the laundry.

I mean, the last two are slight exaggerations. But as Lieberman puts it:

“The more we study the effects of HIIT, the more it appears that HIIT should be part of any fitness regimen, regardless of whether you are an Olympian or an average person struggling to get fit.”

Honestly, if you could do only ONE type of exercise, out of cardio, lifting, and HIIT - it should be HIIT. It is the maximum positive effects for your health and fitness in the minimum possible time. Here’s a comprehensive list of the benefits.

What benefits does HIIT drive?

Improves fat burning efficiency and burns twice as much fat as traditional cardio.

Drives significantly higher post-exercise EPOC.

Improves VO2max, and drives better blood oxygenation.

Drives greater stroke volume, and greater cardiac contractibility, ~10-15% more than regular cardio.

It drives vascular adaptation, making your heart chambers larger and more elastic, improves the size and elasticity of your arteries, and increases the number of capillaries.

It drives hypertrophy - the relevant muscles get bigger.

It allows you to recruit more muscle fibers, and to do so more efficiently, driving greater muscular force and contractibility.

It improves insulin uptake, and improves the muscles’ ability to transport glucose overall.

It increases mitochondrial production and turnover, leaving you with more and “stronger” mitochondria.

Relative to traditional moderate-intensity cardio training, it drove a 41% increase in pain tolerance, and a 110% increase in race-intensity output time before dropout in one study.

My personal favorite HIIT recipe (because it involves the least time, equipment, and overhead), the one that I recommend to friends, is to do 8 sprints. You sprint all-out, literally 100% effort, for 30s, then rest for 1 minute, then do it again, 8 times. That’s 4 min total sprinting, and 8 min total resting, for a complete HIIT workout in only 12 minutes. All you need is some sort of clock - a watch or a phone. And I guess shoes, if you wear shoes running.

We evolved to be both fast and strong. You should live up to that evolutionary heritage - do HIIT.

But SHOULD you wear shoes running?

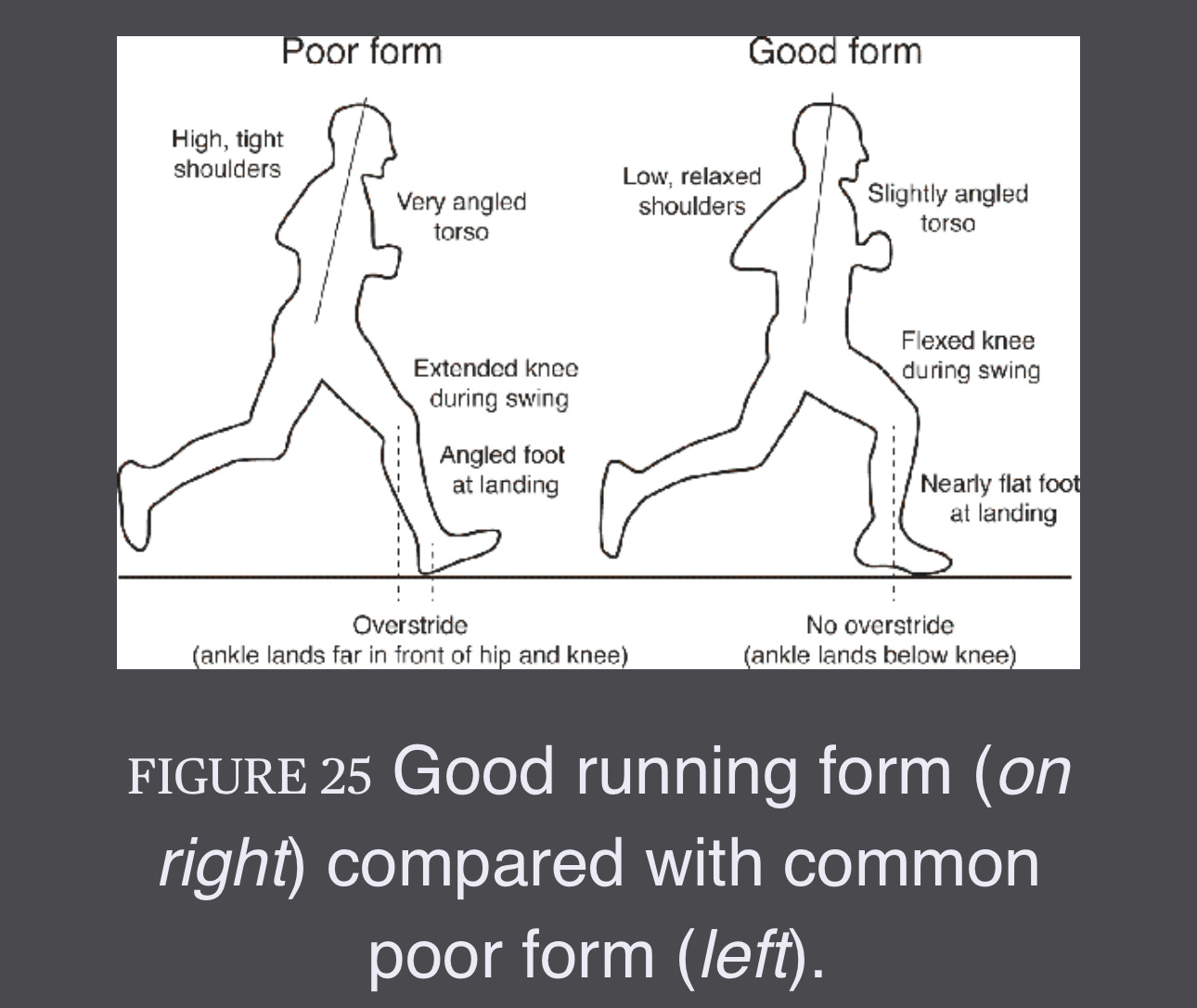

As one of the most prominent academic studiers and advocates of barefoot running, Lieberman suggests you should at least TRY running barefoot. It generally improves form, leading you to land on the balls of your feet and lean forward into better running form. But Lieberman himself ran with shoes for many years (and still might, it’s actually not clear in the book, though he does run a “barefoot running” event with Erwan La Corre).

But you know, as long as you DO get out there and run, or swim, or bike, or do SOME form of endurance cardio, shoes or not, is the important thing.

Also, he has one pretty useful note on good running form - study people who are good at it. That’s what the Tarahumara and Kenyans do, and what many Westerners do NOT do. But the Tarahumara (famous ultra-marathoners) and Kenyans (who dominate all distance running events worldwide) all explicitly model the cadence, stride, “kick,” and posture of the best runners in their groups to get good at running, and it’s probably a good idea.

You can also consult my review on proper running form, which I myself have adopted.

Why should you do cardio if you love lifting?

Basically, most of the benefits that we’ve been talking about - the all-cause mortality, defeating the many diseases of civilization, and so on - come from sustained physical output over time, and weight lifting doesn’t reach that sustained level.22

If you really, truly hate cardio, at least do HIIT three to five times a week. You can spare 12-20 minutes,23 and it will get you most of the important benefits.

But there’s still something to be said for raw capability too. I was a strength athlete - I know the siren call. I was big, I was strong, I looked impressive, it’s all upsides. But are you *actually* fit if you can’t even run a mile without running out of breath? And that’s one thing HIIT doesn’t get you - actual endurance capability.

I think true fitness requires a good aerobic capacity. You can look huge and deadlift and squat 5 or 6 plates, but if a random civilian could outrun you, are you actually fit? Shouldn’t you be able to outrun any random person, if you could grab any random person, huck them onto your neck and shoulders, and squat them for reps? Running fast depends on strength - shouldn’t you USE that impressive leg strength in some domain where it’s actually functional?

Finally, looking impressive and being strong is great and all, but if you can’t consistently deliver a high capacity energy output over a decent amount of time (say 30-60 minutes), I fear you may disappoint some or all of your partners in the bedroom. And then what was looking impressive even FOR? About which, more anon.

Okay. But exercise is hard, isn’t there some way to make it easier and more fun, to increase adoption and uptake?

“According to a 2018 survey by the U.S. government, almost all Americans know that exercise promotes health and think they should exercise, yet 50 percent of adults and 73 percent of high school students report they don’t meet minimal levels of physical activity, and 70 percent of adults report they never exercise in their leisure time.”

Long story short, this is probably hopeless at the population level.

Of the hundreds of interventions to get people to exercise more that have been studied, the strongest effects are generally on the order of “the successful intervention got people to exercise 5 minutes more on average per day.”

And, to be honest, personally when it comes to this, I could really care less about interventions that persuade a reluctant population-at-large to exercise.

We’re obviously differentiating in Western society into castes - much like all good things (height, attractiveness, reaction time, life satisfaction, etc) being positively correlated with “g,” there is a cluster of high human capital people who are the exception to the “70% of Americans are overweight or obese” rule because they exercise and watch what they eat, AND have good careers and are smart and are more conscientious and have better time preference, etc.24

If you’re reading this, you’re probably in that cluster. If you’re not exercising now, I’m hoping to persuade you that you should be exercising.

And as to the differentiation, I say let it happen. Heck, let’s differentiate even more - which is certainly going to happen when effective gengineering becomes a thing, and this class of people are going to start having kids that are athletic 6’ 6” Von Neumann underwear models.25

Lieberman’s suggestions on how to make exercise more fun or sticky at the individual level are pretty limited - exercising in groups like CrossFit or classes, entertain yourself with music or movies, exercise in beautiful environments, dance or play sports.

One thing he doesn’t suggest, and I’m not sure why, is to try to tap into that all-important “reproductive” drive and have really energetic / athletic sex.

I mean, if the whole reason we’re lazy sacks who don’t want to exercise is because the body prioritizes and saves energy for reproduction, why not try to harness that? That argues pretty directly that “reproduction” is the time you should go all out, throw all the coal on the fire, burn as much energy as you can.

I assume he doesn’t say anything like this because it’s not very actionable for the median person, who apparently only has sex once a week, for under 15 minutes.26

But, back to my “differentiation” thing - if you’re NOT median, you should totally do this. Have sex often enough that it takes you 30-60 min at a time, and make it interesting enough,27 and I promise you’ll get some great Zone 3 and 4 time if you’re doing it right.28

But, whatever. Exercise is never going to be adopted by most people. It’s hard, it requires conscientiousness, it requires going against millions of years of inbuilt drives to conserve energy (unless you do the sex thing).

It’s only for the select few, and I am trying to induct you into the Mystery and convince you that you should be one of those few.

So let’s talk about WHY exercise is so good for you.

Don’t regular runners blow out their knees and overly stress their cardiac systems and whatnot? Didn’t the founder of some running magazine die of a heart attack in his early fifties?29

“Exercise is done against one’s wishes and maintained only because the alternative is worse.”

George Sheehan

First, it’s actually probably more that “being sedentary” is bad for you than that exercise is so great in and of itself - exercise at a cellular level beats you up. Weight training literally shreds your muscles, and the micro-tears recover and make the muscles bigger only over time.30 Endurance exercise is a brutal grind that can give you knee injuries, shin splints, tendonitis, plantar fasciitis, lower back pain, and more. And that doesn’t even get into the amount of time it takes! There’s definitely downsides, potential and actual. But, it’s a trade-off.

As Lieberman points out, being pregnant has a lot of similar downsides, people sometimes choke on food while eating, and people trip and sprain their ankles while just walking all over the world. Everything has downsides and risks. Sure, exercise has some potential downsides - but the massive upsides make it worth it.

So why is exercise good for you, on net?

Essentially, hormesis - your body repairs the damage done by exercise, and then a little more. His analogy is that if you spill something on the floor, the floor may end up even cleaner than it was before the spill, because you cleaned the spill up and a little more.

To deal with the damage caused by a workout, you mount an initial inflammatory response, followed by a later anti-inflammatory response to counteract the first inflammation. At the same time, you upregulate a bunch of processes that get rid of cellular waste products, repair DNA mutations, repair damaged proteins, make epigenetic modifications, mend microfractures in bones, replace and add mitochondria, and more. And if you push yourself when exercising (progressive overload), those repair processes actually make things better than before - stronger bones and muscles, better glucose uptake ability in cells, more mitochondria in your cells, and so on.

Much like being sedentary causes chronic inflammation, exercising causes lower baseline levels of inflammation due to the anti-inflammatory responses after the exercise-induced acute inflammation episodes your body undergoes. This is essentially how exercise prevents most of the diseases of civilization, many of which are due to chronic inflammation.

So will all this hormesis stuff lead to weight loss?

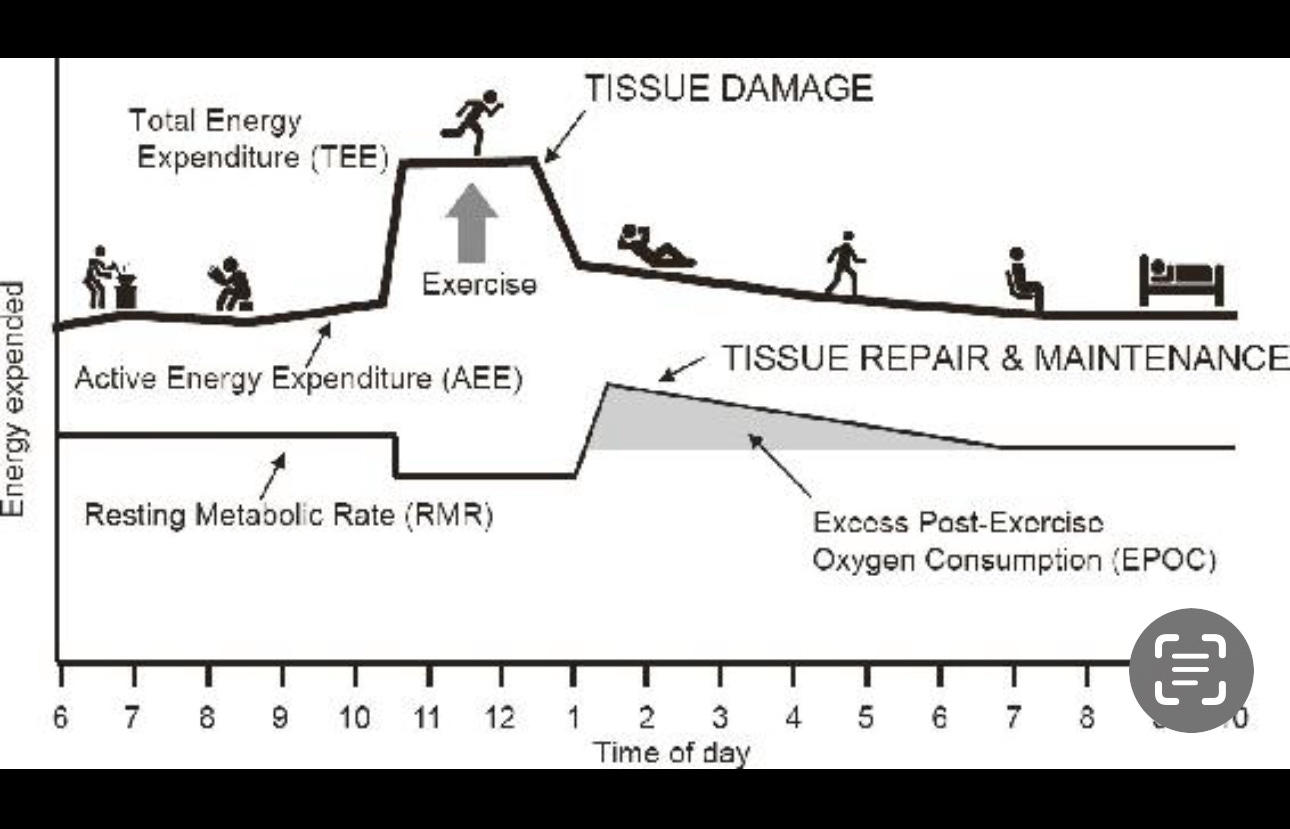

On the one hand, it definitely costs energy:

The EPOC region in the graph is directly higher metabolic expenditure above and beyond the expenditure of exercise itself.

But as we saw in Burn, and in my post on obesity, “weight loss” is the maximally pessimistic, “hard mode” scenario. Basically, no it won’t, because your body eventually compensates for the extra calories burned.

You need to consider those calories burned as eating into your “diseases of civilization” budget, rather than into your “food” budget, because the incremental caloric burn will be compensated away by your body over time. Effective weight loss requires calorie counting AND exercise. Read my review of Burn, or Pontzer’s book itself, for a deeper window into this. Or you know, just get Ozempic or one of the other ‘tides.

But what it WILL do is let you age better!

“The fountain of youth runs with sweat.”

“Many of the mechanisms that slow aging and extend life are turned on by physical activity, especially as we get older.”

We live a lot longer than most mammals. Heart rates vary by size,31 but most mammals get about one billion heartbeats in their lifetime.

Humans, on the other hand, get about 2.5 billion heartbeats. An immense difference! Why is that?

One hypothesis on why that might be is the “grandmother hypthesis.” We have been selected to survive when older, even when post-menopausal and no longer able to have kids of our own, because grandmas are a powerful enough force on their grandchildren’s survival that it actually shows up in natural selection.

Because what do grandmas do? They feed those grandbabies!

Isn’t that the median “grandma” experience? Coming over and she’s just cooked or baked something delicious, and she wants to share it with you, her grandkids?

Well, it’s true even at the hunter gatherer level. Grandparents exist to feed their grandchildren. Hadza grandmas forage longer and bring more calories home than mothers. Mothers forage for 4 hours, grandmas 5-6, and all those extra calories end up in kids and grandkids for the most part.

Wait a minute, don’t hunter gatherers have an average life expectancy of 40 or something? How are there even grandparents around??

That’s a common misconception.

“Contrary to the widespread assumption that hunter-gatherers die young, foragers who survive the precarious first few years of infancy are most likely to live to be sixty-eight to seventy-eight years old.”32

Basically, even without modern medical care or antibiotics, hunter gatherers live roughly as long as average Americans. AND they live that lifespan in much better health, and with many fewer reductions in capability due to aging.

Hey, maybe this “exercise” stuff is looking like a better deal!

Lieberman modifies the “grandmother hypothesis” to the “active grandparent hypothesis.”

As in, grandmas exist to feed their grandkids yes, but the *mechanism* by which they live longer is by being active - by doing that hunter gatherer style foraging, which takes effort. The average Hadza woman walks something like 5 miles a day, roughly ten thousand steps,33 and that doesn’t change much the older a woman gets.

“Human health and longevity are thus extended both by and for physical activity.”

In fact, older hunter gatherer women and men in their 60-70’s in general are on par with Westerners in their 40-50’s. There’s no decline in walking speed among Hadza women as they age,34 grip strength remains notably higher in both hunter gatherer men and women into their 70’s relative to Westerners, and more.

In terms of general ill health before death (morbidity), you won’t be surprised by this point to hear that exercise and activity has huge effect sizes there, too. Exercising vastly compresses and limits morbidity, too. Not only will you live longer, but you’ll also be healthier for much longer than a sedentary modern.

Just look at that HUGE 25+ year “dark gray” delta between Westerners who exercise vs those who don’t. Look at the big difference in “functional capacity,” which boils down to quality of life. That can be YOU. So you can very nearly put “aging” (or at least “aging badly”) into that “diseases of civilization” table.

Broadly, if you care about your health, a life well-lived, exerting your fullest powers along lines of excellence, preserving those fullest powers as long as possible, or seeing your grandkids and hopefully great-grandkids, you should exercise.

Okay, okay. I’m sold. Exercise matters, you’ve convinced me, I’ll do the thing. How much do I have to do?

First, more is always better.

“What about all those marathoners who die of heart attacks?”

He actually relates several anecdotes about some of these cases - basically, they’re one offs, and at the population level, more exercise is always better, going out to 1800 minutes a week of exercise.

But if you want to scrape by at the bare minimum, he agrees with the consensus, largely because it’s clear and attainable:

Do 150 minutes of moderate intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity aerobic exercise per week.

Strength train in a way that hits every major muscle group 2x a week.

Sounds easy, right?

Surely you can devote a less than 1% of your hours per week to your health and longevity?

But of course if you go by what the good doctor actually believes enough to do himself, this is a guy who runs marathons against horses.

Intermediate and advanced marathoners generally average 35-70 miles per week. Given that he runs at a worse than 10 min pace,35 he probably spends 6-12 hours a week running, or 2-5x his “recommended” 150 exercise minutes if most them were “moderate” - given he recommends HIIT about as strongly as you can, it’s probably a safe bet he does HIIT as well, so a fair amount of “vigorous intensity” exercise is probably in there too.

So if you go by “do what I do, not what I say,” the Harvard authority on exercise whose book we’re reading recommends roughly 6-12 hours a week of moderate intensity cardio,36 plus the two weight training sessions and HIIT.

But even if you can’t do as much as our horse-marathon Harvard prof, as little as 90 minutes a week has a lot of benefits:

“In every study, the largest benefit came from just ninety weekly minutes of exercise, yielding an average 20 percent reduction in the risk of dying. After that, the risk of death drops with increasing doses but less steeply. If we assume the studies’ median to be a reasonable guide, to attain another 20 percent reduction in” “risk beyond the benefits of ninety weekly minutes, we’d have to exercise another five and a half hours for a total of seven hours per week.”

So what if you wanted to keep your investment at ONLY 90 minutes a week, but like the typical min-maxer, you wanted to wring the most impact out of that 90 minutes?

If you're going to do only 90 min, here's what I would personally37 do with 90 min:

HIIT sprints 3x a week at 12 min each.

Cross-fit style weight training38 3x a week for 20 min.

My reasoning is this combination will actually hit the 75 minutes of “vigorous” exercise per week AND hit the weight training recommendation, so you’d be fully in compliance with the consensus exercise recommendations AND getting HIIT, all while spending only 90 minutes a week.

HIIT is much more "benefit per minute" than any other type of cardio. That 12-20 minute session is worth 30-60 min of "regular" cardio.

Crossfit, because that way they'll also be cardio sessions, while hitting every major muscle group in only 20 min.

You can stack the HIIT and cross-fit workouts on the same days if you've got the stamina, and then you're fitting it all in at only 3 gym trips a week. But if you can't stack in the same workout, that’s fine, it’s probably better to do *something* spread out over 6 days a week anyways.

If crossfit is too much for you and you’re a newbie, look into super slow weight training, where you can lift just 10-20 minutes a week for strength and hypertrophy benefits.

Finally, the biggest and most life-changing thing for myself (and a couple of other people I've convinced) would be a treadmill desk for your daily work / internet activities,39 and I would actually recommend that over gym exercising if you could really only choose to do one thing (because you’ll get hours per day of movement every single day versus moderate or vigorous movement only 3x a week). Especially if you WFH, it's life changing.

So, what else would you get from reading Lieberman’s Exercised yourself after reading this review?

A well crafted, wide-ranging narrative by somebody at the peak of his field, who deeply understands every aspect of what he’s writing about.

A bunch of fun stories and anecdotes I left out - like the hyena one! Or the one about him going to an MMA cagefight, “armed only with my post-doctoral student Ian.”

You’d probably get more personal motivation to exercise given the additional evidence and stories he goes into.

More detail and deep dives into cellular metabolization, specific mechanisms by which exercise improves your health, and specific cuts of exercise being good for health, aging, etc

Is that enough good stuff to be worth reading a thousand plus pages? Beats me, that’s your call. I thoroughly enjoyed reading it, but I’m a nerd who loves exercise to begin with. I hope I’ve covered most of the important and a good chunk of the fun and interesting parts and put them here in this review for you.

And remember! You, yes you, can live longer and better, and live in MUCH better health and with better quality of life, if you exercise.

If you liked this review, here’s a link to an index of my fitness posts.

With a whopping h-index of 75 and more than 150 papers, many in Nature, Science, or PNAS.

“Four health behaviours combined predict a 4-fold difference in total mortality in men and women, with an estimated impact equivalent to 14 y in chronological age.”

Khaw, K.-T., et al. (2008). Combined impact of health behaviours and mortality in men and women: The EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Population Study. PLoS Medicine 5: e12.

Also for exercise specifically, 4x just in the “exercise” category from sedentary to high exercisers: https://imgur.com/HLiuVJp

And for a mere 300% markup! 😂

A specific Hunter Gatherer tribe in Tanzania that Lieberman has spent a lot of time studying. The Hadza are quite interesting - language and genetics studies indicate they’ve been there for around 50k years, so they’re probably pretty close to “legacy” modern H Saps. Their language is a linguistic isolate. They’re not genetic isolates like the San (who amazingly, diverged ~200kya and have been relatively genetically isolated since), but are still fairly distinct and continuous.

Hahaha, those lazy little…wait a minute! I should invent DoorDash for chimpanzees!! Betting on laziness has enabled trillions of dollars worth of economic activity and revenue, it’s never the wrong bet!!”

Light activity: cooking, slow walking

Moderate activity: rapid walking, yoga, digging

Vigorous activity: running, jumping jacks, walking up a steep incline, walking with a significant load (30% or greater than body weight).

You can’t fully eliminate it because of modern diet and pollution, which also contribute. Another advantage hunter gatherers have - no antibiotics, no plastics, no pesticides, no air pollution. If you’re a fan of Stephen Skolnicks substack about gut microbiomes, you’ll probably be able to think of many ways having a really healthy microbiome and no external pollutants is good for HG health and life expectancy.

And realistically, what percent of the US do you think walks significantly MORE than 1500 steps a day? I’d guess less than 50%?

Think being trapped in traffic, or endless pointless meetings at work, or any of the other endless Sisyphean trudges bureaucracy and modern life subjects people to.

My lifetime best purchase by FAR has been my treadmill desk - it’s almost certainly the highest value thing I own in terms of utility / dollar spent.

I like to think of this as the vindication of all the high energy and ADHD people in the world over the ages who were always seen as a problem in classrooms. Classrooms are trying to kill your kids by forcing them to sit 8 hours a day, and fidgeters will outlive sedentary “good students” and inherit the earth!

Actually one of the things I really loved about the book is that Lieberman digs down to the source of some of these things. The original crazy estimates of chimp strength hail from John Bauman, a biology teacher and football coach who rigged a crude dynanometer in a zoo to measure chimp and orangutan strength, and ultimately used the data from only one particularly “malicious and devious” chimp named Suzette.

“Bauman’s amateurish estimate of Suzette’s strength using an untested, uncalibrated, and probably inaccurate instrument is still cited regularly despite repeated failed efforts to replicate her feat. In 1943, a Yale primatologist named Glen Finch carefully replicated Bauman’s experiments on eight adult chimpanzees, none of whom could muster more strength than adult male humans. A generation later, U.S. Air Force scientists devised a bizarre contraption—resembling a cross between a metal cage and an electric chair—to measure how much force chimps and humans could generate when flexing their elbows. The only adult chimpanzee they managed to train to use this device was about 30 percent stronger than the strongest human also measured. More recently, Belgian researchers showed that seventy-five-pound bonobos can jump twice as high as humans who weigh twice as much, indicating that both species jump the same height per pound.”

“Finally, and perhaps most definitively, a laboratory analysis of muscle fibers demonstrated that a chimp’s muscles can produce at most 30 percent more force and power than a typical human’s. Although these studies differ in terms of methods, they collectively reveal that adult chimps are no more than a third stronger than humans.”

http://www.pnas.org/content/114/28/7343

Rogue chimpanzees are EVERYWHERE.

Muscle wastage that happens as you age.

Via fostering denser and stronger bones.

Running until your prey is exhausted, then killing it, which likely started with running-towards-vultures-scavenging with H Habilis, and has multiple variants, to the aforementioned scavenging, from peak heat persistence running that ends with the animal overheating, to Sámi pursuing reindeer to exhaustion on cross country skis, to native Americans running buffalo off cliffs or into blinds or traps.

Which combined with the Achilles tendon, helps reuse about half the energy that hits the ground while running, via tendon-as-springs style storage and release.

There’s a color difference! Fast twitch are pink and white muscle fibers. White is the “power” type of fiber, which puts out a lot of instantaneous power, but runs out of steam quickly. Pink is in between - moderate force, over moderate time.

Slow twitch fibers are red.

In studies contrasting HIIT and moderate-intensity fitness interventions over six weeks, fitness, V02max, and lactate threshold increase by roughly the same amount in both groups. But the HIIT group had a 41% increase in pain tolerance, too. AND the HIIT group lasted 148% longer in race conditions, compared to a mere 38% improvement from the moderate-intensity group.

(Martyn Morris and Thomas O’Leary, Learning to Suffer… (2017)

Wear a heart rate monitor while lifting, and you’ll see what I’m talking about. Sure, you may reach the top of your Zone 4 in your heaviest weight * reps sets, but there’s a LOT of empty Zone 1 time in there. Real cardio is sustained Zone 3 or higher.

I mean, if you’re a Westerner, your daily “leisure time budget” is probably:

Small screens: 3-8hrs a day

Big screens: 2-5hrs a day

“You know, after a long day spent staring at screens of various sizes, the thing I most want to do when I get home is to relax and stare at my big screen, while still checking my small screen regularly.”

It’s the equivalent of a hair salon paying for a Bloomberg terminal in terms of efficiency and benefits. YOU CAN SPARE 12 MINUTES FOR HIIT.

And in terms of us creating castes - assortative mating for elites has been an amazingly strong force historically (read Greg Clarks The Son Also Rises, or my review, for just how implausibly strong), but it is also getting *even stronger* even in gen pop recently according to genetic studies (Sunde 2024). And the areas it’s getting stronger in are things like SES, educational attainment, etc.

Ideally, my own later kids or my grandkids - I really don’t get why people are against gengineering, seemingly worldwide. Won’t somebody PLEASE think of the children??

If GPT-4 can be trusted on the matter. I’ll dig into the studies eventually.

Also, this is hilarious, because the male bias in sex studies is always to exaggerate - they exaggerate their dick size, their number of partners, whatever. So “once a week” is their EXAGGERATION?? 15 minutes is OPTIMISTIC? Man am I glad I’ve never lived in the “average” world.

Also, how do the women involved in this get off in the <15 minutes allocated?

I have an effortpost on “how to have good sex” around here somewhere that I’ll probably post some day.

But until then, get into whatever kinks or scenarios make sex more fun. If it’s not fun, if it’s not intrinsically 8+/10 exciting, WHAT’S THE POINT??

Seriously, we spent something like a billion years of evolution to get you to enjoy sex. Get on the train and appreciate the fact that literally countless eons of ancestors worked really hard to get you to a point you could both have it and enjoy it.

“Clearly spoken by somebody young without kids,” well no, it’s not, I’m neither. I mean, you get time away from kids. School, baby sitter, nannies, grandma time, whatever. Just don’t be so tired and bored with each other that this seems ridiculous. And it’s a MUCH better use of “adult time” than going out to eat or streaming the latest time waster.

Well, not a magazine but close enough. Jim Fixx wrote The Complete Book of Running in 1977.

As a young man, he was a heavy smoker, lived on junk food, and weighed 100kg (220 lbs). Given his dad lived the same lifestyle and had his first heart attack at 35 and his second fatal heart attack at 43, Jim decided to try to avoid that fate when he turned 35.

He gave up cigarettes, improved his diet, and started running. He became a marathoner, eventually lost 60 pounds, and wrote his book, which became a best seller. He died 7 years after publishing his book, of a massive heart attack while running alone on the roads of Vermont at 52.

So clearly, there were massive genetic confounds, likely an underlying cardiac weakness / abnormality, and his death may well have been prevented if he had been near a hospital instead of on rural night-time Vermont roads when it happened.

That’s why it’s called “getting shredded.” 😂

With mice having a frantic 500-700bpm and blue whales 2-10bpm, humans and medium to large dogs are 60-100bpm.

Gurven, M. and Kaplan, H. (2007) - Hunter-gatherer longevity: Cross-cultural perspectives. Population and Development Review 33:321-65

Another fun little thing he’s chased the source down on. Where did the infamous 10k steps come from? “In the mid-1960s, a Japanese company, Yamasa Tokei, invented a simple, inexpensive pedometer that measures how many steps you take. The company decided to call the gadget Manpo-kei, which means “ten-thousand-step meter,” because it sounded auspicious and catchy. And it was. The pedometer sold like hotcakes, and ten thousand steps has since been adopted worldwide as a benchmark for minimal daily physical activity.”

Whereas Western women go from 3 feet per second at under 50yo to 2fps by the time they’re over 60.

His horse marathon time was 4:20, and it was only 25 miles for some reason.

This would actually shake out as some days with no or small runs (ie only HIIT), and probably several days with 2-3 hour runs, given that you have to actually chalk up continuous mileage to train for the longer marathon distance.

But you would also probably get pretty much the same benefit if you practiced it as 1-1.5 hours a day of moderate cardio, or 30-45 min of vigorous (Zone 4) cardio.

Speaking as somebody who's read many books on both lifting and endurance training, who competed as a regionally competitive powerlifter for 5 years, who swims at least 10 fifties every day, many at sprint pace, who runs triathlons, etc

First workout alternating back squat and bench 5 sets 10 reps at a weight you struggle to finish the 10th rep.

Second workout alternating deadlift and incline bench 5x10 same effort level.

Third workout alternating OHP and front squats 5x10.

Each of these three workouts should fit into 20 minutes.

Once again, best purchase of my life BY FAR in terms of benefits per dollar spent.

I found my way here, finally, from ACX Open Thread 353. There, last October, I was skeptical whether we really *know* that exercise benefits health. Could this all be bullsh*t, like perhaps the standard praise for fruit and vegetables? Now I finally found the time to follow it up (a bit). In that ACX comment thread, you linked to your review of Lieberman's book here. And to me specifically you quoted the following passage from the book (also part of the review here):

> "In every study, the largest benefit came from just ninety weekly minutes of exercise, yielding an average 20 percent reduction in the risk of dying. After that, the risk of death drops with increasing doses but less steeply."

So I looked that up now, the referenced paper Wasfy & Baggish 2016, and it turns out the studies he refers to in this passage are all observational only. "To date, there have been no randomized controlled trials designed to examine the impact of PA [physical activity] on mortality." And yet Lieberman writes "came from", and such language is standard for that section in his book, a section which shows no awareness that higher mortality and physical inactivity could easily be both caused by a third factor. That's enough to undermine my trust in his theories. If he discusses the issue elsewhere in the book, your review doesn't mention it.

Speaking of the review, I found the style different, for better or worse, from that of, say, an ACX review. It doesn't seem like an open-ended investigation. In particular, take this passage:

> "Sitting slows the rate we take up fats and sugars in the bloodstream, and whatever isn't taken up will turn into fat. Sitting is usually accompanied by psychosocial stress, and that stress increases cortisol and makes you pack on organ fat. Another way it increases inflammation is [...]"

The point about stress is a confounder! Perhaps it's, not actually the physical non-activity of sitting, but the stress (associated with it for other reasons) that impairs health? That should have gone on the other side of the ledger! But you just pile everything on one side, on the pro-exercise side, and that's true for most of the post.

Meanwhile, the Morris studies you invoked in the ACX thread aren't quite as convincing as I first thought, since presumably people partly self-selected into the different jobs, such as bus driver vs ticket taker, depending to how comfortable their bodies feel with PA.

Of the evidence presented for the health benefits of PA, I find the Danish two-weeks study most convincing. You invoked it to me in the ACX thread (and you also note it here in the Lieberman review), so thanks again for that.

And I should make it clear that in that thread you recommended your Lieberman review to someone else. Not to me, the skeptic, whom a more open-ended investigation would have suited better. Finally, let me also say that I found the writing here good and entertaining --- I'm not surprised that the Substack has been catching on quickly. On this older post I'm the only commenter (as of now) but on newer ones such privilege would be very unusual.