Proper running form and better breathing patterns

from Brian Mackenzie's Power Strength Speed

“How you run is more important than what is on your feet. Good running form can happen both ways, you can run poorly barefoot, and extremely well in a shoe.”

—Daniel Lieberman, Harvard anthropologist and physiologist, author of the “Born to Run” Nature Paper, author of Exercised

As I have moved from the world of competitive strength and back to long-form endurance and triathlon training, I have been trying to improve my form.

It’s a daunting undertaking, especially if you have any sort of history of endurance exercise.

Everyone has more or less found a form they can live with, and relearning that form slams you right back into “beginner” status again, with the corresponding drop in pace, times, and endurance as you try to slowly find your way to a whole new running mechanic. Everything feels wrong. You feel SLOW, you feel weak, you feel anew the burning hatred of running that we all seem to harbor from time to time. Distances that you used to easily breeze through can physically and mentally shatter you, at first.

Most coaches don’t even bother to try to teach you running form - many feel that form takes care of itself as long as you put in the miles.

Ken Doherty in Track and Field Omnibook:

“Running technique is primarily an individual matter. A sound rule of thumb when it comes to running technique is to leave it alone. Do what comes naturally, as long as ‘naturally’ is mechanically sound.”

So why SHOULD you try to relearn your running form?

How about because a full 85% of runners succumb to injury at some point?1

Not just that, but “some point” may come sooner than you think - researchers at Harvard looked at injury rates in competitive distance runners in a 2011 retrospective study and found that 75% had a moderate to severe running injury each year. A 2012 Harvard study found 79% dealing with injury each year.

Famed running coach Alberto Salazar, a former Boston and 3x NYC Marathon champion, saw his career flare out due to poor running style leading to knee and hamstring injury. He became a strong advocate of proper form for his athletes.

“You show me somebody with bad form, and I’ll show you someone who’s going to have a lot of injuries and a short career.”

His form improvements led to Galen Rupp claiming the first Olympic medal for an American in the 10k in 48 years in London 2012 (a Silver). And the runner who won gold in 10k and 5k, Mo Farah, was ALSO one of Salazar’s “form improved” athletes.

And form is definitely a risk factor in injury - in the 2011 Harvard study, heel-striking runners accounted for most of the injuries documented, and they had approximately twice the rate of repetitive stress injuries versus forefoot strikers.

Shoes won’t save you either. After all, all of those injured runners were wearing shoes, often the most “advanced” and “state of the art” running shoes available.

Dr. Nicholas Romanov, Mackenzie’s mentor and creator of the Pose Method:

“The human body is made of 100 trillion cells that are the product of millions of years of evolution, and your pair of $80 shoes that you developed over the last year is going to improve on this?”

So why take the trouble to learn how to run properly?

Most of all, it will help prevent injury, and allow you to keep training and being fit

Running with better form is more energetically efficient, and you can achieve better times and longer distances when you have good form

It reduces wear and tear, and so improves recovery times

What does proper running form look like?

We’re going to break it down piece by piece, but let me give you a high-level overview. If you imagined that you were a stick with a big wheel on the bottom, what would you look like when you were moving forward? You’d be leaning forward, and your wheel would be turning, right? Sort of like a Segway.

This is basically the theory behind proper running form - you want to let gravity do as much of the work as you can get away with. You want to be leaning and “falling” forward, instead of springing jauntily from step to step, because it’s more energetically efficient. You also want to minimize unnecessary movement and prevent bad form with the rest of your movements, to maximize energy efficiency and minimize risk of injury.

This is achieved with the following cues:

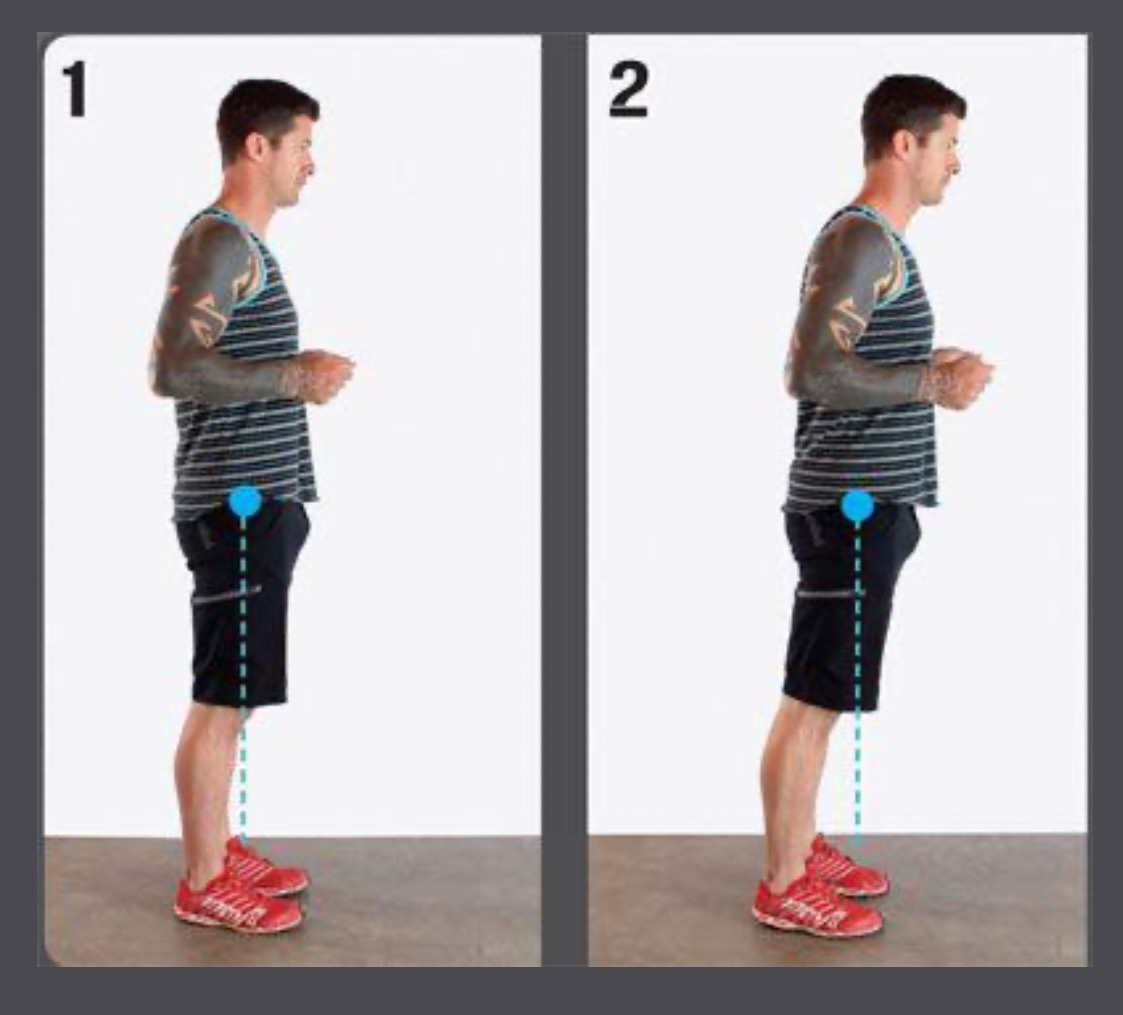

Maintaining proper posture and position

Develop a proper forward lean

Land underneath your center of gravity

Strike with your forefoot

Pull your foot up with the hamstring

Step with a rapid cadence, with brief contact time

Maintaining proper posture and position

Proper posture shifts the impact and stress of running from the knees to larger muscles that can take the abuse, mainly your core, hips, and hamstrings.

It has three main elements:

Midline stabilization - your core needs to be tight to shift the load away from your knees to your bigger muscles. Mackenzie advocates for about 20-30% core engagement, ie your abs should be 20-30% tensed. You need a tight core for “falling” and letting gravity do the work. And be aware - this is usually the first thing to go when you’re tired, and “Once midline stabilization is lost, mechanics are compromised, fatigue sets in, and risk of injury dramatically increases”

Neutral head position - If you put your thumb on one clavicle, and your pinky on the other, and stick your index finger straight up, your chin should just rest on it. Your head should be neutral - not looking down or up, not shifted forward or back.

Arm position - Your arms should be close to your body, at a 90-degree bend, with shoulders drawn back a little. If you made a thumbs up in this position, the thumbs are pointing at the sky, but close your thumbs to run. They should also be relaxed - your arms aren’t there to work, but to provide balance and stability as you run. One common fault is shoulders alternating back and forth as you move, but the shoulders should remain square and fixed, because your core should be engaged.

Develop a proper forward lean

Stabilize your core, make sure your head is neutral, and get your arms into position. Now lean out over your ankles - you’re shifting your center of gravitational mass forwards. Lean enough that you need to move a leg forward to catch yourself - this is the essence of running while letting gravity do the work. Instead of pushing with muscle power for each step, you’re letting gravity do half your work.

Land underneath your center of gravity

Torque is created when you lean far enough forwards to initiate running. To keep up (and keep running), you need to move your feet beneath your new center of gravity. The stronger the “lean,” the farther out your center of gravity, the faster you need to move your feet, and thus the faster your pace.

Strike with your forefoot

Your feet are an exquisitely designed shock-absorbing energy-reuse system. From the arch of your foot to the achilles tendon and the muscle structure and ligaments, your feet have been honed over millions of years of hominin evolution to enable running.

But to take advantage of all this shock-absorption and energy reuse, you have to land on the ball of your foot. You want to do this anyways, because practically all running injuries stem from poor striking.2

So, land on the ball of your foot, but unless you are sprinting near your max, your foot should be relaxed enough that your heel should touch the ground after the ball for a fraction of a second before you transition back to the ball to move forward for the next step.

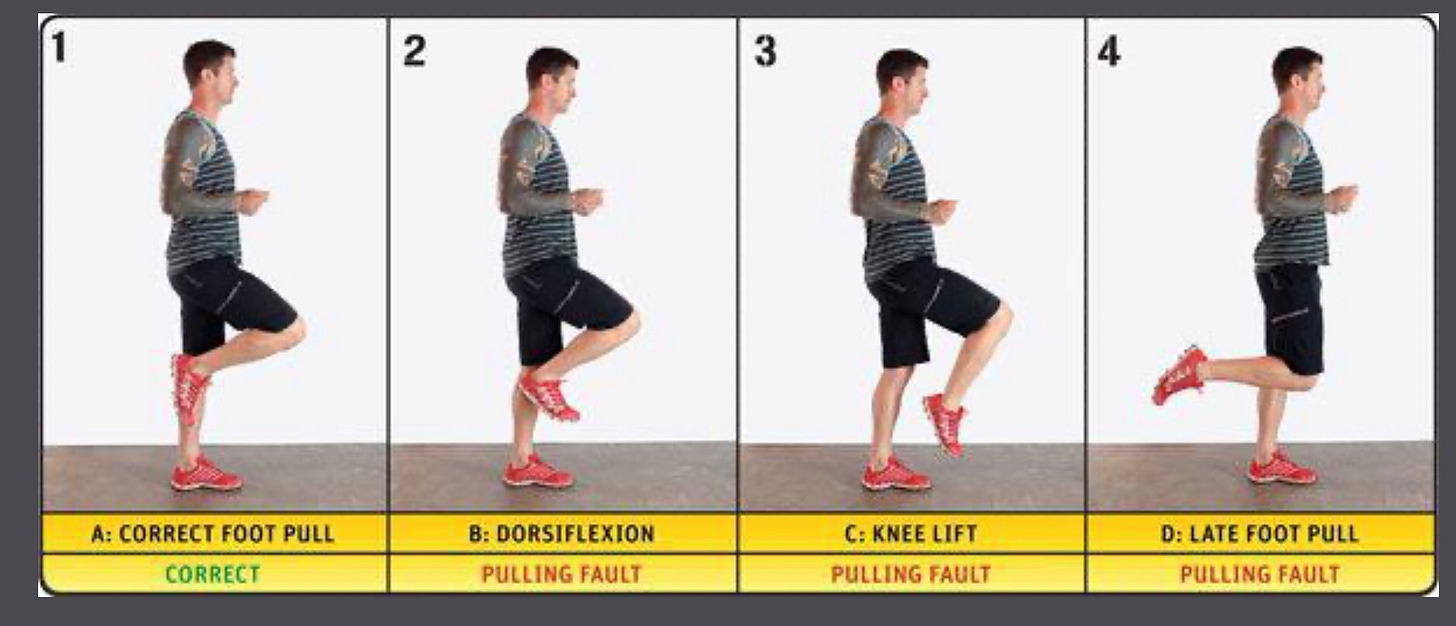

Pull your foot up with the hamstring

To execute a well formed foot pull, draw your heel towards your butt using the power of your hamstrings, while maintaining a neutral foot position. You are not lifting your knee up at all - your pulled foot should be directly in line with the opposite leg, and centered directly under your center of gravity.

Pulling mechanics change with speed - the faster you are running, the higher you need to pull your foot to your butt, and in maximum effort sprints, you’re pulling all the way to your butt.

Step with a rapid cadence, with brief contact time

You want to shoot for at least 180bpm, or ~3 steps per second. Mackenzie suggests getting a metronome app, and playing it at around 90bpm, and syncing your left or right foot to it. And 180bpm is the minimum you can go that won’t compromise muscle and tendon elasticity - faster cadence is better.

You also want to keep contact time brief. When you’re doing higher cadences, it actually decreases the force of each footfall, because you’re moving less per step, and it’s easier to keep contact time brief, as well as making it less likely to be injured.

“Walker and Salazar found that the best runners slapped the pavement so quickly and lightly with their forefoot that contact seemed incidental.” Like a "pogo stick with a stiff spring”.

Drills

The best thing about Mackenzie’s book Power Speed Endurance is the extensive drills and pictures he includes. If this review has intrigued you enough to actually tackle relearning a better running form, I think that getting the full book is a good idea. It also covers cycling and swimming form!

I’ll be doing a “swimming form” review in the next couple of weeks, after I have adopted better swimming form myself and have seen some pace and distance improvements. I’m definitely in the “puppy uglies” right now though - I swim breast stroke for 20-30 fifties on my distance days right now because my currently-transitional freestyle is so bad I gas out after around 10. 😂

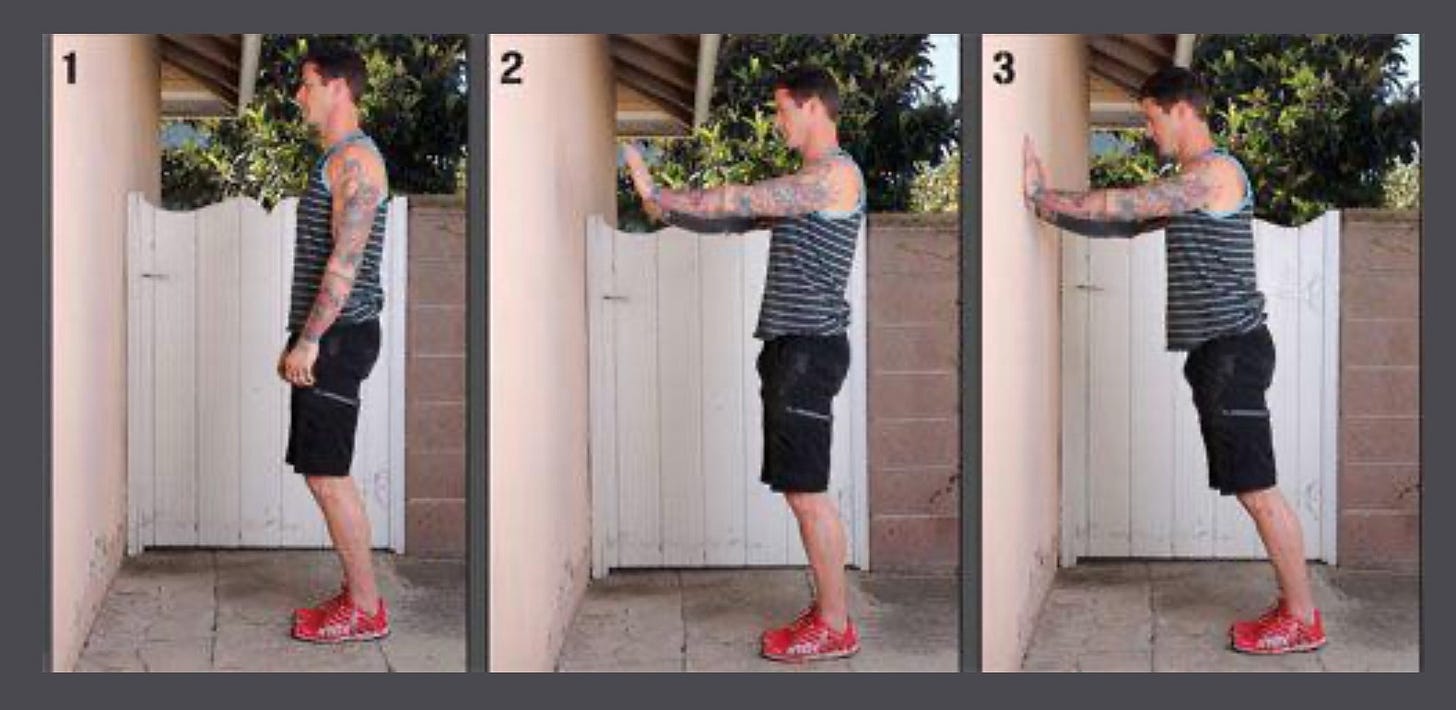

Falling Drill - Wall Falls

Stand a few feet away from the wall, in proper running stance. Midline stabilized, neutral head.

Extend your arms in front of you, then lean forward with your posture stabilized - your core is still engaged, your head is still neutral.

Repeat 20 times.

Pulling drill - Wall Pulls

Position your heels 3-5 inches away from a wall, facing away from the wall

Establish your running stance, and pull your ankle toward your butt using your hamstring.

Do 20 pulls, then switch legs.

Common faults are pulling the knee up or kicking the wall with your heel. Keep the knee of your supporting leg soft, pull your ankle to knee level, maintain a neutral foot, and use the hamstring only, not the knee, to pull your foot.

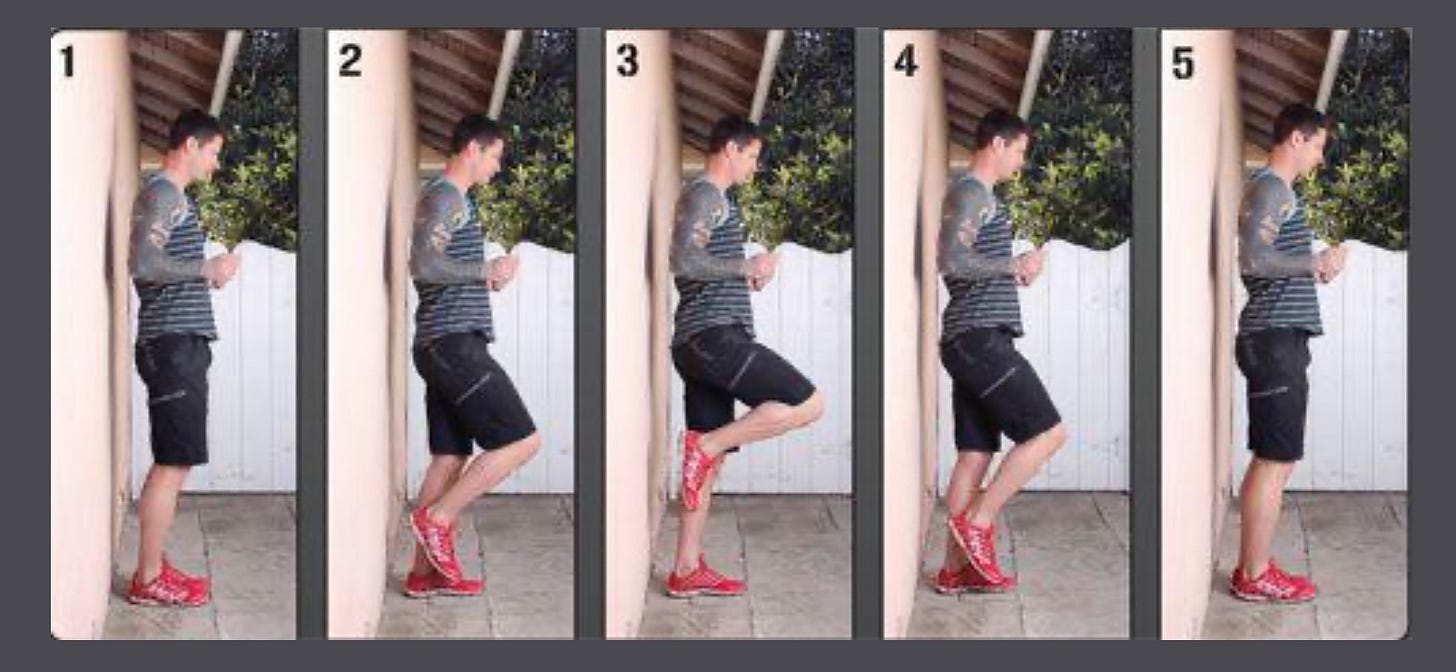

Running Wall Drill

Start like the Wall Fall drill - in running stance, stabilized midline, neutral head, leaning forward into the wall a few feet away, with your arms straight ahead.

Now begin running in place using all the previous mechanics - keeping your core engaged, keeping your head neutral, pulling with your hamstrings.

Repeat 10-20 pulls per leg, then take off runing alongside the wall, keeping the same lean, core stability, neutral head, and pulling mechanics you just performed at the wall.

Running form cues recap:

Maintain posture

Lean and fall

Land under CGM, with the appropriate amount of lean for your speed

Pull your foot up with your hamstrings

Ball of the foot with heel check

At least 3 steps per second pace, 180 bpm

Film and form check

You need film to get crucial insight and feedback on your form. Video doesn’t lie, or have an ego, so it’s invaluable for getting *actual* improvement. You need somebody else for most videos, but you can try a treadmill and a tripod, too.

Film at a couple of speeds - you may have great form at slow speeds, but break down at high speeds

Take video both when you’re fresh and fatigued. Fatigued video is great because it shows where your form starts to unravel.

Film yourself at the beginning and end of intervals, or do them on a treadmill and film all the way through

Film yourself at the beginning and end of a 5k or 10k

Breathing

I was going to review Budd Coates’ Running on Air, but after reading it I realized you can break it down to a few points.

Broadly, most injuries occur when you’re exhaling on a footfall, because core strength is compromised. Worse, most people breathe in an “even” rhythm and are always exhaling while striking on the same side, wearing that side more and increasing the risk of injury on that side of the body.

Coates’ solution is to breathe in a 3/2 rhythm. Inhale for 3 steps, then exhale in 2 steps. This forces you to alternate the side you’re exhaling on. For faster efforts, you go down to a 2/1 rhythm, of breathing in for 2 steps and breathing out for 1.

I’ve also experimented with doing a 2/3 rhythm for Buteyko breathing, but it didn’t really do much for me. I think if you’re going slow enough for Buteyko breathing to be possible, you can just do 3/6 or 4/8.

What does better running form *feel* like when running?

I for one, really appreciate the clear directions he’s given us, because I think it’s fairly easy to optimize a given motion once you’re out there putting the miles in, but the specific attractor you’re optimizing towards can vary pretty widely.3

For instance, I used to sprint by moving my knees a lot, and who *cares* if it’s not energy efficient, it’s a *sprint* the whole goal is to USE maximal energy (at least in HIIT sprints) for all those muscle, mitochondrial, and VO2max benefits.4 And I got cleaner and more efficient at driving those knees up in my sprints, as part of optimizing by doing, but I probably would have never arrived at “only use your hamstrings, never the knees.”

So I’ve put maybe a hundred miles in using the new form at this point. I’ve definitely noticed that you can achieve a lower energy expenditure in this method. There’s an attractor down there at the bottom of the well where you can really feel yourself exerting less and less energy the more you follow the form strictly. He mentions in his book several times that core engagement and midline stability is the first thing to go, and I have noticed this, even as a former strength athlete. I imagine for the typical endurance athlete it could be even more of an issue, and indeed it’s why he advocates strongly for strength training improving your running times.

I feel like I get 5-10% more distance for the same amount of exertion or effort with the new form. I haven’t noticed much difference in sprints, but I haven’t been able to sprint on a track yet, just on treadmills with steep inclines, and I think any benefits would be more likely to come in flat sprints (a steep incline forces you into a lot of the recommended form anyways).

But I’ve seen strong enough results to believe there’s enough lift that it justifies writing this review and evangelizing better running form more broadly.

What would you get from the book itself?

Much more detail, theory, justification and drills

Bonus sections on cycling and swimming form that are just as detailed

Bonus sections on strength training, mobililty, and nutrition and hydration

Tons of programming and training templates

One of my favorite sentences from a 2023 paper’s abstract:

“Despite decades of high-quality research, running remains the most common cause of exercise-related musculoskeletal injuries and rates of overuse running-related injuries (RRI) have not appreciably declined since the research began.”

But this is also why I like Mackenzie - like him, I advocate for putting in at most 50 miles a week, and making as many of your workouts HIIT as you can, because injuries are directly correlated with how many miles you put in, and there’s actually very little incremental improvement over 50 miles. Whereas something like 90% of marathoners incur an injury while training, and typically log 100-150 miles a week.

Here’s why forefoot strikes and hamstring pulls are better:

Of the 103 participants, 25% of the sample (15 males and 11 females) reported an Achilles Tendon running related injury on the right lower limb during the 1-year evaluation period.

A midfoot strike differentiated Achilles tendon injuries (odds ratio [OR], 2.27;

A more flexed knee at initial contact (odds ratio = 1.146, P = .034) and at the midstance phase (odds ratio = 1.143, P = .037) were significant predictors for developing AT RRI.

Similarly, on this “it’s easy to optimize once you know the right target” front, I tried to reach Jhana 1 or 2 for a year or two while meditating before I read something from somebody who framed it like “it’s just finding a little bit of joy and pleasure in whatever you’re feeling at the moment, then focusing on it and growing it in your attention.”

Once I realized you can find a little spot of joy or pleasure, and then optimize towards it, just keep diverting your attention to more and more of it, I was able to reach Jhana 1 and 2.

Actually I’ve been compiling a master list of study-verified HIIT benefits, so I’ll collate them here for the first time:

Improves fat burning efficiency.

Drives significantly higher post-exercise EPOC.

Burn twice as much fat as traditional cardio.

Improves VO2max, stroke volume, and cardiac contractibility ~10-15% more than regular cardio.

Drives more muscular force and contractibility, vascular adaptation, oxygenation, insulin uptake, and mitochondrial production.

Improves pain tolerance - 41% increase in pain tolerance vs LISS

Improves pace and endurance - 148% longer before time to failure vs 38% improvement in LISS

Allows you to recruit more muscle fibers

Allows you to recruit more motor units per fiber

Increases muscle size

Makes your heart chambers larger and more elastic

Improves the size and elasticity of your arteries

Increases the number of capillaries

Improves muscles’ ability to transport glucose

Increases the number of mitochondria per cell

Lowers blood pressure 7-15 points

Very useful thank you, as an Amateur runner who’s been running in and off for a year, I alternate between running for a few weeks and taking a few weeks off because of injury. 😭😭 The not swinging your shoulders thing is the most unintuitive tip for me here.