Triathlon-fit in ~10 hrs a week - Beyond Training, by Ben Greenfield

With 80% guilt-inducingly easy training

Ben Greenfield is one of those infohazards who drops actually useful tidbits often enough you’ll pay attention, but hidden in a flurry of product placement and fad-driven actively dumb suggestions that couldn’t possibly be true or helpful. There’s a lot of noise in the signal, in other words, but the signal is juuuuuussst good enough that you’re still tempted to pay attention.

I also have a soft spot for him because he has twin boys, and still trains and races pretty competitively, as well as tries to include them in his life wherever he can.

Ben Greenfield’s essential value prop: he advocates training in a way that you only need 10-12 hours a week to run triathlons. He trains this way himself,1 and also points to Sami Inkinen,2 who’s had a lot of amateur and age group Ironman championships in Sweden, Hawaii, Las Vegas, and Kona, and more. Sami only trains twelve hours a week.

I wish Greenfield had better epistemics, because he performs well enough himself, and he has coached various triathletes3 to impressive performance and finishes, but you can tell he’s placed “has a scientific study about it” in some unquestionable category in his mind, despite nearly all sports medicine studies being hot garbage. His threshold for trying something new is practically nonexistent, as is his threshold for recommending something, and he’s very big on quoting (but not citing) studies he thinks supports whatever he’s telling you to do.

I dearly hope he gets all the branded products he’s name dropping every other sentence for free. I’d also love to see “a day in the life of,” because the way he describes his day, he’s lurching from one crackpot psuedo-technology to another every 15 minutes or so throughout the day. Whole body vibration platforms! Electrical muscle stimulators! One-legged yoga poses on special branded things!

Another “epistemics” complaint - he remarks on a ton of studies in the book, and even puts little citation numbers after them (4), and then never actually cites them anywhere in the book, so for the few cases I didn’t know enough to judge, I had to look studies up myself to judge their quality.

I still think he has some important and relevant things to say about training overall, and indeed, the rest of your life Beyond Training (hence the title of the book).

I’m here to extract the best parts of the book out while leaving all the crap and hucksterism and terrible epistemics behind.

Why I think we should pay attention is summed up nicely in the beginning of the book, as he compares two different triathletes and training approaches:

His first athlete is Chad, a hard charging type-A 58 year old who’s run 12 triathlons over 20 years, and worked his way up to being a CFO at an F500.

“Chad’s routine has been the same ever since he started doing triathlons. He swims for about an hour on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays with a Masters swim group. When he gets closer to his big races, he sometimes throws in an extra pool or open-water swim on the weekends, swimming at a long, steady, aerobic pace for an hour or so.

He rides his bike twice a week for sixty to ninety minutes, sometimes on the trainer, sometimes outside—usually mixing it up with some tempo or interval training and occasionally a spin class.”

He runs 3-4 times a week for 45-60 minutes, typically at the same pace.

Chad is deeply overtrained. His times are declining. He’s got a bad gut, a painful hip, low libido, aches and pains, and bad sleep.

He’s one injury away from wrecking his ability to train entirely, and that injury looms threateningly near.

Greenfield contrasts Chad with Kirsten. She’s 53, does a triathlon a year, and has completed 14. She owns her own graphic design firm, and has similar demands on her time as Chad.

“Her Ironman training routine consists of short dips into intense heart rate zones, followed by long periods of rest, recovery, and light physical activity at her standing desk, in her garden, walking the dog, or even riding her bike to the grocery store and library. She firmly believes that her ancestors didn’t ramp up their heart rates significantly for several stressful hours each day “running from a lion” and that neither should she.”

She doesn’t do long death march runs or bike rides, but primarily focuses on HIIT. She also lifts heavy twice a week.

In terms of life outcomes, he paints her as the anti-Chad. Wonderfully fulfilled, great family and relationships, bursting with life and vitality, practically hovering over the ground, suffused in divine light as a subtle heavenly choir quietly sings hosannahs everywhere she goes…

Obviously he’s stacking the deck in the descriptions, but he’s pointing at something important.

Training quality matters, and training quality is a lot more about “effort” than hours.

Also, the rest of your life matters too - not just your training, but your diet, your relationships, and your “exercise-life balance.”

Chad’s whole training life was spent in suboptimal zones, as we’ll find out, and he spent a lot of time on it that could have been used on relationships or other nice things in life. Kirsten trained smart, probably put fewer hours in, and had better relative performance and a much better life. We obviously want to aim at that side of the “training-life balance” ledger!

Back to training quality - most people spend way too much time in “pain caves” while training, but you’re actually much better off if the majority of your training time feels guilt-inducingly easy, and the minority is stomach churningly hard.4 Think 80/20, Pareto principle, polarized training.5

And this is something most people get wrong, even when they know they should be doing it. Even when they explicitly aim for it!6

Broadly, you should spend ~80% of your time barely in “cardio” heart zones, nowhere near your lactate threshold (60-75%). As much as you can should be high intensity, above lactate threshold - that usually shakes out to 8-10%, because that’s the most “actually high intensity” even elite athletes can take. Only 10-12% of training should be near-but-not-above lactate threshold heart rates.

I’ve mentioned “lactate threshold” here - but none of us have a “lactate meter,” just heart rate monitors. How to translate lactate threshold to heart rate?

Lactate threshold to HR mapping test protocol

Method 1 running: Run at the hardest intensity you can maintain without bonking or slowing down for 30 minutes. Your heart rate average across the last 20 min is your lactate threshold heart rate.

Method 2 running: Perform three 5 min as-hard-as-you-can-without-slowing runs, with 5 min of rest in between. Average your heart rate across the three running segments.

Cycling 1: Warm up with 10-15 min of light cycling, then do one of the two running methods. This is better on an indoor course or trainer, to avoid traffic or unavoidable interruptions.

Cycling 2: Warm up, cycle for 8 min as steadily and as quickly as possible up a 2-3% incline, at 80-100 RPM. Rest for three minutes (or descend), and ascend again. Average your HR in the two climbs.

Swimming 1: You can swim at your max sustainable pace for 1km, but this is pretty hard, because pacing is harder in the water. If you’re used to it though, crank it out. I personally bring a big clock with seconds and set it outside of the pool to see my splits. Take your total time / 10 - this is your Critical Swim Speed - basically your 100m time at lactate threshold.

Swimming 2: Warm up swimming gently for 10-15 min. First swim 400m at your max sustainable pace. Rest for 5-10 min. Then swim 200m at your max sustainable pace. Then you do 200 / (T400 - T200) to get your time in m/s, then convert that to a time per 100m to get your critical swim speed.

So now you have a heart rate (or swim speed) that defines your lactate threshold. Being close to your lactate threshold is “pain cave” training, and it actually beats you up too much to be useful. At the same time, you should routinely EXCEED that threshold to actually get stronger and faster. Choosing the right balance between those things is how you can train and be triathlon-fit in only 10 hours a week.

Which brings us to the perennial sheep/goat dividing training element - HIIT.

Because what does HIIT do for us?

Improves fat burning efficiency.

Drives significantly higher post-exercise EPOC.

Burn twice as much fat as traditional cardio.

Improves VO2max, stroke volume, and cardiac contractibility ~10-15% more than regular cardio.

Drives more muscular force and contractibility, vascular adaptation, oxygenation, insulin uptake, and mitochondrial production.

But you still need some amount of traditional aerobic cardio, because you only get endurance Qmax and cardio respiratory benefits from long aerobic training. You can’t move the needle on “how much blood your heart sends to your muscles” without it.

Greenfield points out something interesting here - most studies finding 80/20 to be optimum are in elite athletes who compete as their job and train 20-40 hours a week.7

But most people reading this book (or review) aren’t full time athletes - we all have jobs and families and lives.

So if the maximal optimum requires 30+ hours a week, what if you only have 10 hours a week to devote to fitness?

The overall idea is that if you don’t have ~24-32 hours a week for aerobic training, you can sub as much HIIT as you can still recover from fully, and be better off.

It’s important that your remaining aerobic volume isn’t so hard that it interferes with your overall recovery too - HIIT is *hard* when done properly. But it should be your priority. The key phrase for your remaining aerobic work is “guilt inducingly easy.”

“Guilt inducingly easy” translates into something like 60-75% of your lactate threshold heart rate. That is *really* easy! Think jogging, or comfortable cycling with no hills. It is *extremely* tempting and easy to go over it, because it doesn’t even feel like a workout. But you need to resist, and actually do the *easy* thing in this case, because it allows you sufficient recovery to put your HIIT work in.

Yes, you still need traditional cardio to build your VO2max engine - but make sure it’s easy enough you don’t overtrain. About which, more later.

So if you only had ~10 hours, what’s a sample training plan that makes sense?

Monday: 30 minutes easy bicycling skills and drills; 20 minutes easy swim drills

Tuesday: 20 minutes heavy barbell lifts; 30 minutes run HIIT workout

Wednesday: 30 minutes bicycling HIIT workout; 30 minutes swim HIIT workout

Thursday: 20 minutes heavy barbell lifts; 30 minutes easy run drills

Friday: 60 minutes injury prevention (e.g., training weak links of your specific body) and core training, yoga, or an easy swim

Saturday: 2.5 hours of 20 minutes on, 5 minutes off cycling intervals at race pace; 3 × 1,000-meter swim at race pace

Sunday: 60 to 90 minutes of 9 minutes on, 3 minutes off running intervals at race pace

The other thing to do to maximize your limited training time is going Beyond Training - that’s right, we’re talking lifestyle changes and interventions.

One thing he advocates, which I’ll strongly second and third, is filling the day with as much low level activity as possible.

This dovetails nicely with what we know about activity levels in hunter gatherers, too, and is recommended by everyone who knows what they’re doing, like Dan Lieberman.

What does this shake down to? Use a standing desk, or much better, a treadmill desk, as much as you can. Commute by foot or bicycle. Don’t sit motionless for more than an hour, fidget, get up, do pull-ups or jumping jacks.8

Greenfield also advocates cold showers, cold exposure, breathing, and lifting something heavy every day, all of which I endorse and do myself.

I tackle breathing and cold exposure here as I review Scott Carney’s books The Wedge and What Doesn’t Kill Us.

What else can do to make your limited training hours more impactful?

The confluence of things Greenfield recommends and I endorse from other sources or personal experience:

Over speed and under speed training9

Hypoxic and breathe restricted training10

Cold exposure11

Passive and active heat exposure (sauna, steam room etc)12

Very slow eccentrics / isometrics when lifting.13

Greasing the groove14

Pay attention to or improve your form - my review on proper running form is here.

Finally, do resistance training, take it seriously. All too often, cardio people don’t want to, but it’s a mistake. In one of the few studies he actually attributes:15

“The adaptations may include an increase in mitochondrial enzymes, mitochondrial proliferation, phenotypic conversion from type IIx towards type IIa muscle fibers, and vascular remodeling (including capillarization). Resistance training to momentary muscular failure causes sufficient acute stimuli to produce chronic physiological adaptations that enhance cardiovascular fitness.”

Yes, resistance training takes time and adds more to your physical load and fatigue, but good news! If you’re new to resistance training, there’s a good chance you can improve your strength and muscle mass by training only 20 minutes a week.

He actually makes many more recommendations that I consider not really supported by literature or elite coaches, which I’ve left out. For your viewing pleasure, I’ll foot note them here.16

Tradeoffs

Everyone needs an order of prioritization on what’s important when other things have to give. With limited training hours, and with trying to have actual lives outside of training, it’s important to have thought this through beforehand, so you can make better decisions in the moment. Here are some quick heuristics:

Prioritize endurance cycling, swimming, or running if pressed for time or if you need to cut something for recovery. Specific training is always the most important.

Do strength training after cardio.

Space training the same muscle groups at least 48 hours apart.

“Short and frequent (2-3 20-45 min per week) or long and infrequent (1 50-70min per week) should define your strength-training workouts.” So if you skipped one workout and are only getting one strength workout this week, go long.

Do only one long run in the buildup to a race.17 The rest should be intense 60-90 min runs.

At a macro-cycle level, make cuts in off-season training if possible. Got a vacation planned? Make sure it’s during the off season. Expecting a visitor or business travel or something that’s gonna whack your training? Schedule for the off season if possible.

Recovery

Recovery is probably the most important thing in training - it’s certainly the combination of “most important and most frequently neglected.”

But eating enough, making sure you sleep well, and making sure your training load is building you up rather than breaking you down is literally the only way to get better consistently. And if you don’t do those things, you’re just throwing most or all of your training hours away, retroactively making them pointless, so it’s pretty key to fitting all your training in only ten hours a week.

Greenfield’s idea of doing recovery well is just a bunch of gimmicks in the book where he’s trying to recommend various dumb products. But recovery is a legitimately important topic that people seem to take for granted, or at least not try to optimize in the same way they try to optimize their workouts.

So allow me to include the “Recovery Pyramid” from Renaissance Periodization’s book on recovery, because Dr Mike and the other RP folk deeply understand it.

My more comprehensive RP recovery review is here.

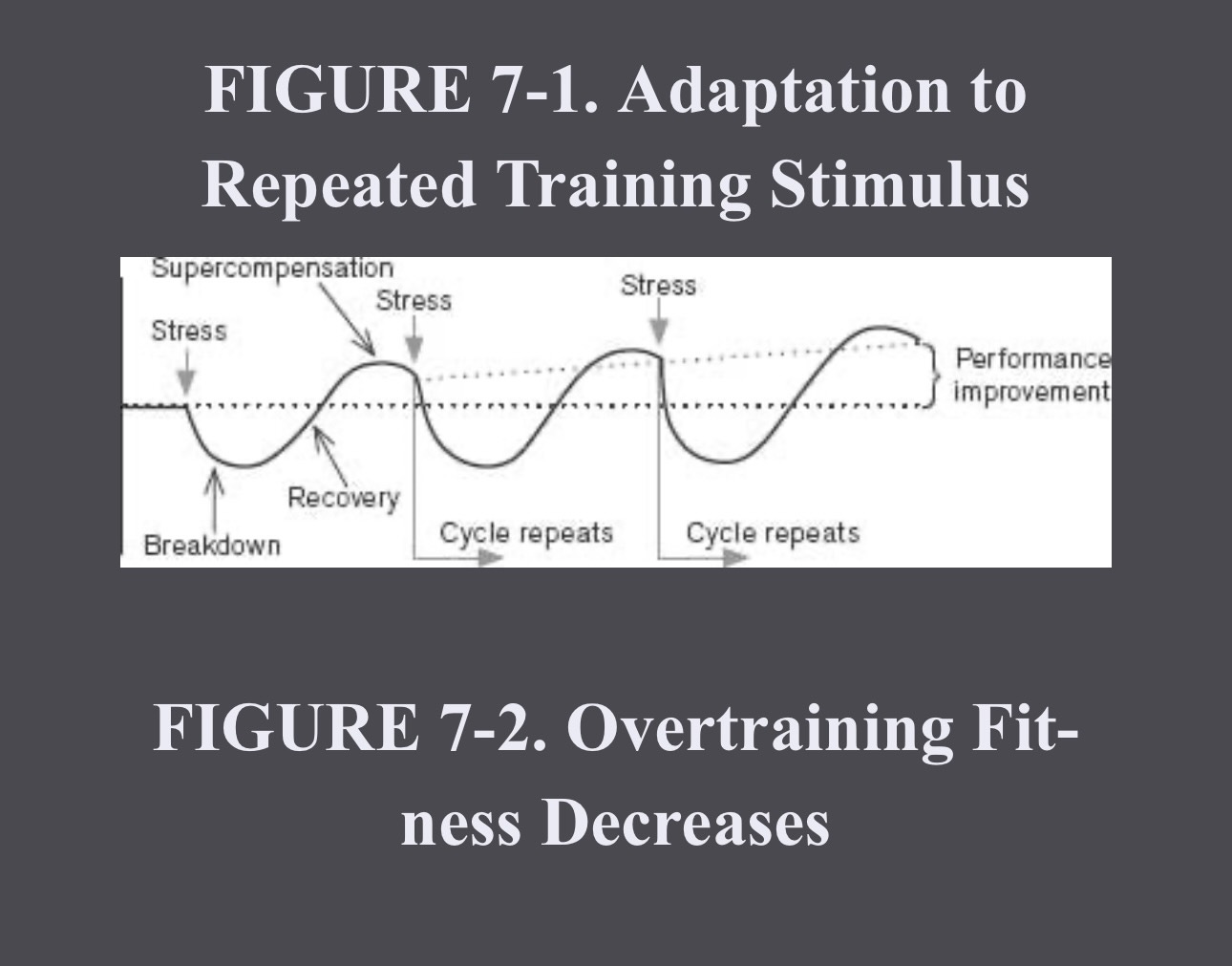

And what does proper recovery get you? Supercompensation.

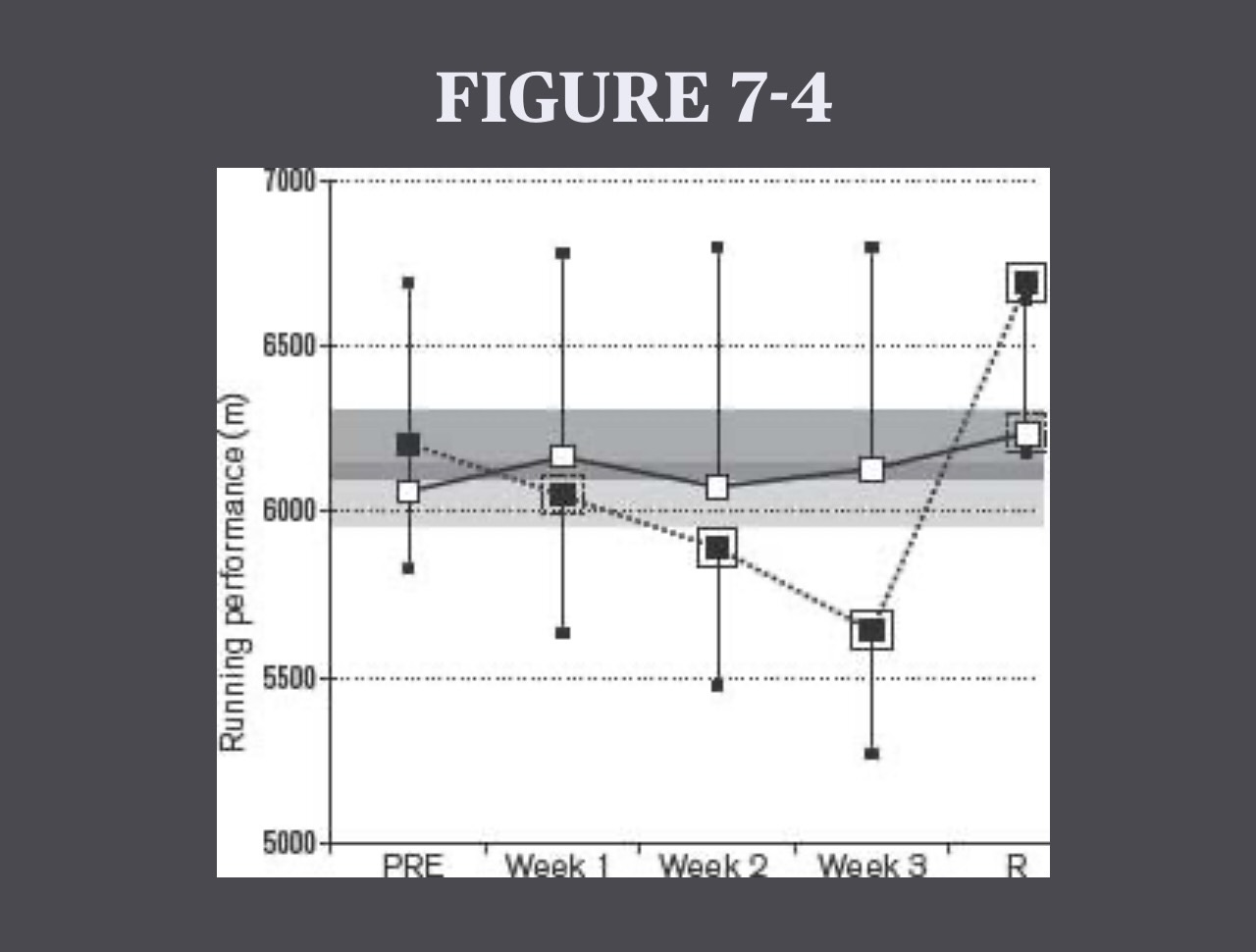

In one of the other studies he actually attributes, a study in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise divided triathletes into two groups: Both groups trained regularly for one week, but for the next three weeks, one group ramped up training volume by 40%, with the other control group staying the same.

Both groups then tapered for a final week before a performance test. The goal was functional overreach in the 40% group, and then supercompensating, or bouncing back more fit than before.

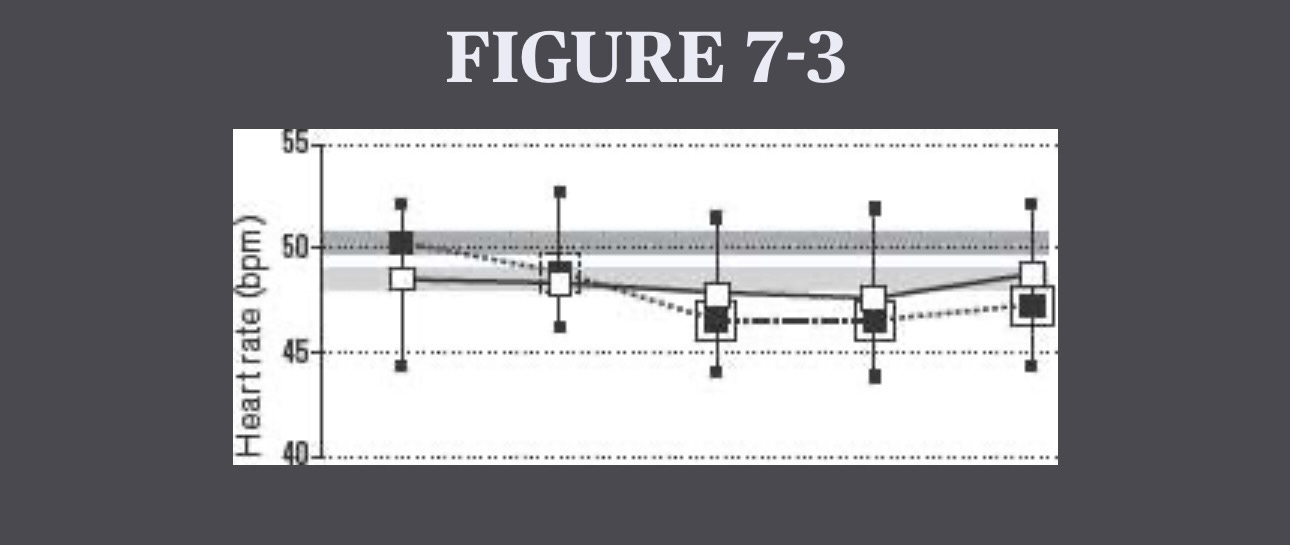

Below you can see the two groups heart beats while training (white control, black 40% group).

Because they were already fit triathletes with low resting heart rates, the dip in average HR indicates a real load is being put on their body over these three weeks - and that’s overreach.

They had both groups do a run-to-exhaustion test at the end of each week in the training period, and one final one after the taper week:

Look at that gap! If you overreach, then recover, that’s the sort of trends you’re putting your body through - a cyclic-but-trending-upwards fitness trend.

So recovery - pay attention, and do it right, because doing it well is key to maximizing limited training hours.

In the meantime, sleeping and eating seem important to touch on, as they are key to good recovery.

SLEEP.

It’s important, it’s neglected, it’s how you grow stronger, better, and more efficient.

Once again he’s a 50/50 mix of solid advice and absolutely ridiculous huckstering. I’ve extracted the good stuff, and added some that he missed.

Sleep hygiene:

Wear a sleep mask

Block blue light from devices

Stop using devices a few hours before bed

Stop eating several hours before bed

Melatonin 0.3mcg

If you’re prone to stuffy noses or allergies or breathing problems, I have to advocate for the single biggest “sleep improver” I’ve experienced myself: Rhinomed Turbines - a little plastic dongle you put in your nose to breathe better overnight.

Naps:

20-40 min - if you nap longer you need to sleep more

Naps are usually easiest 7-8 hrs after waking

Try to time your naps regularly

Do low stress things before a nap

Don’t nap hungry

Don’t use alcohol or sedatives to nap

Jet lag

Exercise as soon as you can

No caffeine

Naps

He doesn’t mention this, but here’s the SSC jet lag melatonin scheduling.18

Eating and Nutrition

Given his poor epistemics and “jump on every pseudoscientific fad” mentality I expected him to be in some gibberingly crazy space of maximal-Californian diet advice.

Only eat fruits with rinds on odd calendar dates, and you’re only allowed to eat meat that you’ve raised, released into the wild, hunted, and killed with your bare hands, and similar.

But it wasn’t actually so bad! In fact I agree with nearly everything he suggests as good advice.

Prioritize whole foods

Prioritize short and simple ingredients lists without vegetable oil and added sugars and preservatives

Nut butters over peanut butters

Try to rinse, soak, and sprout grains

What’s good for you to eat?

Eggs

Organ meats

Shellfish

Cold water fish

Natto19

Dark green or colorful vegetables

Sea vegetables such as nori, kelp, dulse, algae, spirulina, and chlorella

Fermented foods such as yogurt, kefir, kombucha, and sauerkraut

Turmeric/curries

High calorie and tasty recipes

I’ll also include some of my own staple “meal prep” meals here, because it’s hard to get enough calories even when you’re merely a recreational athlete.

What is “meal prep?” It’s when you gather all your ingredients for as many meals as you’re meal prepping, and prepare and store all of your meals for the week on a single day of the week. (I do breakfast and lunch and then usually freestyle dinners, but if I’m really against the wall time-wise or trying to meet a difficult weight goal, I’ll meal prep all three meals). Now anytime you want to eat, it’s waiting for you, already made - I just pop the glass container in the microwave, or pop the blender cup in the blender, and I’m ready to eat in 5 min. It’s also WAY better (in taste, calories, and macros) than anything you could get at one of the restaurants in or around your work campus.

It legitimately saves something like 5-8 hours a week if you track it, because it eliminates a lot of time deciding and debating and shopping and preparing and cleaning up. Or worse, debating, deciding, driving somewhere, waiting, waiting again, waiting again again, eating, and driving home.

To the calorie point, I’ve never understood the people who complain that “exercising doesn’t move the calorie needle” - I routinely burn 1k+ calories in my average lifting workout, as measured by a Polar heart rate monitor. I pretty much always struggle to get ENOUGH calories. Heck, just last week I was feeling extra hungry and looking a little smaller and wondered why, and then found out I’d been *inadvertently* burning an extra 700-800 calories a day on my treadmill desk!20

That aside, here’s four meals I routinely do in meal prep that average about 1,000-1,500 kcal each:

Chia pudding21

Blueberry and spinach shake22

Crackleur pork belly with zesty brussels sprouts23

Blueberry Apple Nut Steel cut oats24

And my tips to calorie up any given meal:

If it’s savory, add butter, thick cut bacon, lots of cheese, or bacon crumbles (the kind with only “bacon” as an ingredient, like you get from Costco or Sam’s)

If it’s sweet, add chia seeds, heavy cream, butter, peanut butter or nut butter

Other food related stuff:

He has a section on gut microbiome and health, which is an issue for a lot of serious endurance athletes. It’s easy to get leaky gut and bacterial overgrowth / SIBO, especially if you travel for races. The risk factors are high carb diets, overtraining, and travel / exposure to pathogens in food and water.

Although you definitely need to carb load for 4-6 weeks before a race, and you need carbs for actual racing, altering your macros towards more fat and fewer carbs outside of races is probably a good idea - it improves your fat metabolization overall, and although - as we saw in Endure - you need carbs for actual racing or “sprint” efforts, many athletes who have positively moved their fat metabolization post personal bests.25

If you’re having a lot of digestive and pooping issues, have your stools tested for microbiome and parasites.

If you have a problem from the tests, do a microbiome reset. I’m gonna link microbiome scientist Stephen Skolnick’s idea of a reset here, because Greenfields idea of a reset is crap.

He has a section on what not to eat during a race, which I think is actually Opposite Day. No gels or sports drinks while racing, no or limited caffeine, completely against very well supported recommendations and actual elite athlete behavior. I recommend you DO eat caffeinated gels and sports drinks.

On the “I agree” end, he recommends blended shakes, white rice, sweet potato and yam the day and morning before, and avoiding fiber the day of your race because of delays in gastric emptying.

He’s (inevitably) big on toxins and cleanses and detoxing and all sorts of hoohaw. The only things on this front I endorse are:

Multiple strong HEPA grade air purifiers in your house if you live in a city or near a road or volcano or other source of emissions26

Get your water report, and get a good reverse osmosis filter if you don’t like what you see.

Wash any store bought fruit and veg with soap and water and a scrubby brush.

The risk of not recovering properly - Overtraining.

I think his overtraining section and advice is probably the strongest in the book, and he actually includes several useful diagnostic tests.

Overtraining is the great bane of the conscientious and the overachiever - we’re always tempted to just push ourselves harder, and to demand more, *especially* if we’re tired or aren’t really feeling it. But if you actually care about performance, you need to care about recovery and what your body is actually capable of - overtraining is when you’ve pushed too far.

How to tell if you’re overtrained?

Triangulate three to four signs to know:

Sleep: Poor sleep, low sleep quantity, tiredness, insomnia.

Soreness: if you’re slow and tired and achy consistently for a week or more.

Appetite: if you’re not as hungry as usual for several days, or if you’re losing weight.

Changes in HR or HRV:27 either up or down can mean something, and it’s not a strong indicator, but paired with other reads it can be an extra piece of evidence.

Frequent infections or illnesses.

Energy level - if your mood or energy level has been struggling for a week or more with no good reason.

A lot of these have a lot of overlap with being sick or dealing with a lot of life stress - and indeed, you should also back off on training volume and intensity in those times.

“You need to be able to distinguish between days when you are truly recovered but may just “feel tired” and days when your tiredness indicates a genuine need to rest.

A good way to gauge this is to start your workout, get through the warm-up, and then see how you feel. If you’re still tired after the warm up, you are probably under-recovered.”

Want more “overtraining” tests? Yes, please!

“The criteria for SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome) are:

Body temperature lower than 96.8°F or higher than 100.4°F

Resting heart rate above 90 beats per minute

High respiratory rate (20 breaths per minute or more)

White blood cell count lower than 4,000 cells/mm3 or higher than 12,000 cells/mm3”

Other tests:

Blood pressure test:

Lie down relaxed for five minutes, take your blood pressure. Stand up and immediately take it again. If it’s lower after standing, you have adrenal insufficiency.

Pupil test:

Stand in a dark room with a mirror. Shine a light from the side of your head on your eyes. The pupils should constrict and stay constricted. If they constrict, then dilate, or flutter back and forth, you have adrenal insufficiency.

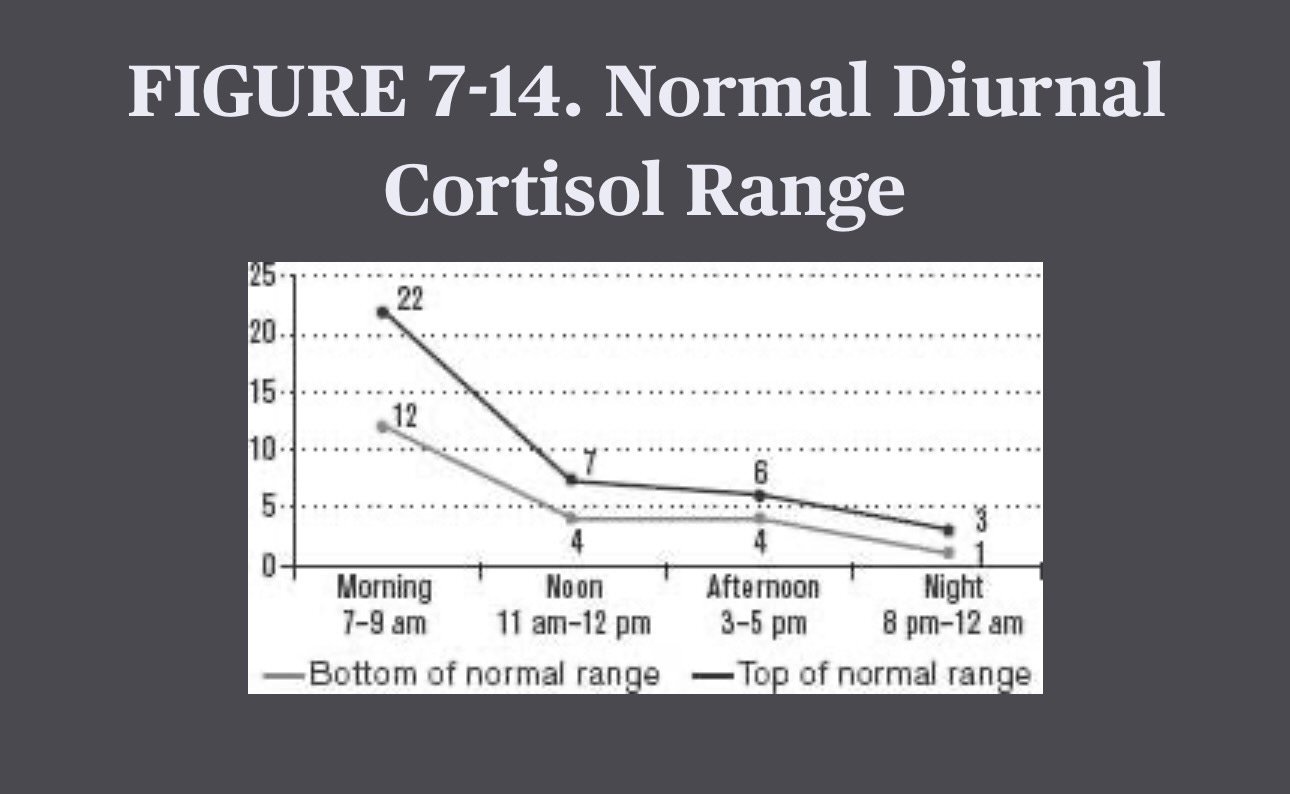

Cortisol tests:

If you really want a better read, spit in tubes four times a day and look at your cortisol trends.

What to do if you’re overtrained?

Ok, you’ve looked at some of the metrics above, maybe you did the pupil or blood pressure test, and you think you’re overtrained. What now? Well, reduce your training volume, of course.

How much should you back off? You should take deload weeks until you are recovered. As to how many deload weeks, it depends on whether you are simply temporarily over-reached, or overtrained, complete with adrenal fatigue - you might be fine after a week, or it might take months.

And what is the appropriate deload intensity? Think roughly half your usual, across everything - weight or distance or time.

You need to monitor your condition through multiple channels, as before, and make a judgment on whether you’re recovered enough from the aggregate impression you have across your sleep, appetite, energy levels, and HRV while you’re doing your deload weeks. I’d err on the side of caution - we only get one body.

Other tidbits from the book:

His sections on Mobility and Balance were interesting enough to briefly touch on.

Mobility.

I’m actually not sure how useful mobility is to performance, and didn’t want to dig into the studies he mentions but doesn’t cite.28

That said, having decent mobility should definitely be part of a life well lived and being fit, and it certainly seems credible that mobility issues could seriously impact your performance. I’ve never really struggled with it beyond some rotator cuff damage when I was a power athlete, but since other people might, I thought I’d mention it here.

“Mobility refers to your ability to move your body and limbs freely and painlessly through your desired movement.”

Static stretching actually DECREASES performance, which he at least recognizes and warns against. He recommends dynamic stretching, deep tissue work, or traction (like chiropractic work). I don’t really know enough to comment, but I’ve always been a fan of deep tissue massage.

Balance.

Greenfield also points out that if you’re actually fit you should have good balance.

I agree. I think somebody who is “triathlon fit” should be able to do at least half the things at a Ninja Warrior gym - but that’s probably just the life-long rock climber in me talking.

The only two things I remember from a book I read on Feldenkrais and better movement touch on balance:

When you see elite athletes, dancers, or people who seem really graceful and poised, it’s because they are retaining full optionality of movement at all times - in other words, their balance is so good, they can move in any direction pretty much any time, no matter how they are moving.

Good movement always happens in long, graceful arcs and curves. Power and accuracy is transmitted via long curves that route through your core and end at an extremity, and balance is being able to deploy those curves in various positions.

To train balance, he recommends going barefoot, barefoot running, and leg stands and one leg squats.29

I’ll endorse rock climbing and Ninja training as being pretty good for balance, as well as being fun.

Exercise / life balance.

“Let me ask you a question: You don’t want to regret the finish line, do you?

Let me ask you another question: Are you missing the important things in life?

Let me ask you one more question: Is your tombstone or obituary simply going to say, “This Person Was Really Good at Exercising”?”

All great points - for competitive people, their pursuits have a nasty tendency to eat into most other things of value in their life. I’m as guilty of this as anybody, but it doesn’t have to be that way, and it’s something we can do better at.

So what are tips on preserving exercise-life balance, so that we can maintain our relationships and hobbies and outside-of-training lives?

Home gym - I strongly endorse this one - although I love my gym buddies, nothing saves time like cutting out a commute both ways and being ready to instantly start a workout at any time.

Minimize off season training - the way overreach and recovery work is inherently time limited - all you really need to do is maintain your base fitness in the off season.

Do only one long run in the buildup to your race - “typically three to four weeks before your event.” The rest should be intense 60-90 min runs.

Eat lunch fast - I love shakes and meal prep for exactly this reason. I pre-stage all the dry ingredients in 7 shakes at the beginning of the week, so all I have to do is add liquid and blend - 1500 healthy calories that fits my macros and took ~30s to make!

Don’t drive - not only is it a source of major stress, if you live in a real city, you can probably get there faster or about as fast on a bike or on foot anyways.

Outsource everything - grocery shopping is a huge time sink, Upwork and Task Rabbit exist, and everyone with a high powered career and / or training schedule should probably outsource even more than they do now. My favorite tidbit was he outsources waiting on hold on phones to something called FastCustomer.

Include the family - he does this a lot, and I really admire it - he includes his twin 5 year old boys in a lot of stuff, and he takes opportunities to do quick HIIT sprints while playing with them and stuff like that. Great idea. Or you could be like Sami Inkinen and row from Hawaii to California with your wife.

Meal prep - I don’t know how you can NOT do this, honestly. Unless you have a cook, but even then, meal prep is probably still the right move for breakfast and maybe lunch. Between needing to meet calories and macros, and having other things going on in life, this is absolutely key to my own days.

Eliminate TV - god yes. Everyone else: “You know, after a long day spent staring at screens of various sizes, the thing I most want to do when I get home is to relax and stare at my big screen for 2-5 hours, while still checking my small screen regularly.” IT’S A TRAP!

What else will you get from reading the book yourself?

Product placement, product placement, product placement! Actually, I’m not even sure he gets paid for half the stuff he mentions. Even a tenth. I think he just really loves “bleeding edge” and gimmicky stuff, and recommends it at the drop of a hat. But there is a place for some of this stuff - if you really want an edge in a particular area, if you’re dialed in on all the important stuff, why not try something bleeding edge? I think most of us would benefit more from dialing in the known basic-but-important areas, though.

Lots of good race day stories and anecdotes, like the time he ran a half and a full Ironman back to back on two subsequent days, and his hip locked up so much he couldn’t walk.

More detailed breakdowns of the hormonal changes going on when you overtrain (adrenal fatigue, cortisol burnout, etc)

Tons of supplement suggestions, all of which I’ve skipped due to epistemics.

Lots of mentions - but not citations - of studies of unknown quality.

As one example, Ben completed Ironman Hawaii in 9:36 in 2013 on only ten hours a week of training - and Hawaii is a harder than usual Ironman.

The Finnish cofounder of Trulia when younger, now a very impressive triathlete, who also rowed from California to Hawaii with his wife(!). Sadly they’ve only had two children, depriving our world of more undoubtedly very athletic and high human capital people.

TJ Tollakson, for one, who placed first in four Ironmans between 2011-2019 and completed more.

“Stephen Seiler sums it all up quite nicely in a paper that appeared in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance:

Numerous descriptive studies of the training characteristics of nationally or internationally competitive endurance athletes training 10 to 13 times per week seem to converge on a typical intensity distribution in which about 80% of training sessions are performed at low intensity (2 mM blood lactate), with about 20% dominated by periods of high-intensity work, such as interval training at approx. 90% VO2 max.”

In professional swimmers, 77% of their training is done at aerobic intensity. For marathoners, 78% of their miles is below marathon speed, with only 4% at race pace, and only 18% above lactate threshold. Elite Kenyan runners do ~85% of weekly training volume below lactate threshold.

In a study on recreational runners, they tried to test an 80/20 training intervention vs College of Sports Medicine recommended distributions.

“The intended intensity distribution for the two training groups was supposed to be 77 percent low, 3 percent moderate, and 20 percent high intensity in a polarized training group, compared with 46 percent, 35 percent, and 19 percent in a lactate-threshold training group. But heart rate monitoring during the study revealed that the actual intensity distribution of the recreational runners was 65 percent, 21 percent, and 14 percent in the polarized group and 31 percent, 56 percent, and 13 percent in the lactate-threshold training group.”

Sample Olympic training routine:

“A typical day for our athletes starts fairly early with breakfast between 6 and 7:15 a.m., as their first training or practice is at 7 or 8 a.m. It depends on the sport, but most practices are two hours per session and there are two sessions a day, five to six days a week. Their strength and conditioning session is usually one to one-and-a-half hours, with three to four sessions a week. The athletes also get “extra workouts,” which are anywhere from fifteen to forty-five minutes, and focus on their individual needs, whether it’s extra work in the weight-room or addressing a sport skill. Then they have sessions with sports medicine for rehab or recovery work. We spend a lot of time teaching the athletes that recovery doesn’t just happen, they have to work at it. Proper nutrition/hydration and quality sleep have to come first and can’t be overlooked. They have to make time for contrast baths, sauna, compression work with the Normatec system and massage.”

Greenfield advocates “fifty to a hundred jumping jacks, five doorway pull-ups, twenty push-ups or squats.”

They help you recruit more motor units and get better neurological adaptions.

Overspeed - going downhill on a bike (120 rpm+) or while running and moving your legs noticeably faster than you’re used to, “beyond what feels comfortable or natural.” How steep? Pretty steep, but not so steep that you’ll fall, 5% grade is ideal.

Underspeed - Long uphill grinds. Think running uphill or stair-mill with a weight vest, or cycling uphill at 60-70 RPM, or swimming with a drag suit. Chris McCormack famously does a ton of underspeed “grind” sessions on the bike and recommends them because they stave off fatigue in the latter parts of a race.

Improves your performance by strengthening inspiratory and expiratory muscles, with hypoxic getting you more red blood cells.

Altitude is the traditional hypoxic training - go running and biking in Colorado or in Cedar City, Utah the 2 months before a race, it’s absolutely beautiful, and you’ll be King Kong when you’re back at sea level. There’s hypoxic tents and beds if you want to drop some money and not be somewhere beautiful.

For restricted breathing:

Instead of breathing on a 1-2 stroke cadence while swimming, breathe every 3,5,7 strokes. Or my personal favorite, do sprint laps holding your breath the whole way. Or use a swim snorkel with restriction.

For running and cycling, wear a resisted breathing mask for intervals.

AKA cold showers, ice baths, swimming in cold water. Greenfield:

While working at your computer or watching television, wear a Cool Fat Burner vest or compression gear that combines pressure and ice.

Take a five-minute cold shower every morning, or alternate twenty seconds of cold water with ten seconds of hot water.

Immerse your body in an ice bath or a cold lake or river for five to twenty minutes once or twice a week.

When possible, swim in cold water. When the boiler at my local YMCA broke last year and I was stuck swimming in 55°F water for two weeks, I could eat practically anything in sight for the duration and was still losing fat at an unprecedented rate.”

Passive heat exposure is traditional sitting in saunas and steam rooms. Active heat exposure is *training* while in increased heat.

A study of elite rowers saw a 1.5% improvement in 2km rowing performance and 4.5% increase in plasma volume, after active heat training 90 min a day for five days in 104 F 60% humidity. Amazing results for elite level athletes, and for only 5 days of training!

I’ll personally endorse super slow body weight or gym exercises as being *amazingly* hard, and good for getting over a strength plateau. Examples:

Upper-body pushing exercise (i.e., push-up, machine chest press, etc.), 5 to 10 reps of ten seconds up, ten seconds down

Upper-body pulling exercise (i.e., pull-up, seated row, etc.), 5 to 10 reps of ten seconds up, ten seconds down

Lower-body pushing exercise (i.e., leg press, squat, etc.), 5 to 10 reps of ten seconds up, ten seconds down

Lower-body pulling exercise (i.e., dead lift, leg curl, etc.), 5 to 10 reps of ten seconds up, ten seconds down

AKA practice makes perfect - when you’re doing your “movement break” pullups or whatever, do them full range of motion, perfectly strict form, because you’re only doing a few. A lot of adaptations are more neural than physical, and Greasing the Groove perfects those neural pathways.

Specificity + Frequent Practice = Expertise

“Resistance Training to Momentary Muscular Failure Improves Cardiovascular Fitness in Humans: A Review of Acute Physiological Responses and Chronic Physiological Adaptations” in the Journal of Exercise Physiology online.

(The full text is freely available at: http://ssudl.solent.ac.uk/2271)

EMS, “zero gravity” suspension treadmills, whole body vibration, some snake oil “sweat improver,” compression gear, a metric ton of various supplements (all of which are crap except for creatine), a bunch of gimmicky products like Gymstick, Fit10, and PerFirmer, and so much more. Literally half the book is him name-dropping some pseudo-scientific “training aid” - really hope he gets them all for free.

“You heard me right. In your buildup to a marathon or an Ironman triathlon, you really need only one long run—typically three to four weeks before your event.”

Basically, either take .3mg of melatonin 9 hours after you woke up, or right before going to bed in your new time zone.

“Most studies say to take a dose of 0.3 mg just before (your new time zone’s) bedtime.

This doesn’t make a lot of sense to me. It seems like you should be able to model jet lag as a circadian rhythm disorder. That is, if you move to a time zone that’s five hours earlier, you’re in the exact same position as a teenager whose circadian rhythm is set five hours later than the rest of the world’s. This suggests you should use DSPD protocol of taking melatonin nine hours after waking / five hours before DLMO / seven hours before sleep.

My guess is for most people, their new time zone bedtime is a couple of hours before their old bedtime, so you’re getting most of the effect, plus the hypnotic effect. But I’m not sure. Maybe taking it earlier would work better. But given that the new light schedule is already working in your favor, I think most people find that taking it at bedtime is more than good enough for them.”

The famous Japanese fermented “goopy” soybeans - which microbiome scientist Stephen Skolnick recommends as THE biggest single intervention you can do to foster better gut health.

I’m the type of person who looks at the METS or my heart rate and says “well, I can do just a *little* bit better than last time, surely?” But you know, this ends with me walking at 10-15% grades at 4-5mph for hours.

Chia pudding - I usually do a 3-4x recipe of this:

2 cans Thai kitchen coconut cream

1 can TK coconut milk

1.5 empty cans water

1 cup shredded coconut

1 cup chia seeds

1 cup yogurt

2 tbsps liquid vanilla

2 tbsps fresh lime juice

1/3 cup honey

Liberal cinnamon

1/3 amount cinnamon in nutmeg

1/4 amount cinnamon in cloves

Blend in container with immersion blender / stick-mixer, set in fridge overnight to set.

Total macros (3x recipe):

6450 cals 546g fat 114g protein 225g net carbs with generous honey and shredded coconut

Chia Pudding per serving: 921 cals 78g fat 16g protein 32g carbs

Chia seeds 1/2 cup: 520 cal, 28g fat, 28g protein, 0 net carbs 200mg x 4 (1/2 cup) = 800mg potassium

Coconut cream 1 can Thai kitchen 13x60=780 cal, 6x13 =78g fat, 0 carbs, 0 protein, 0 potassium

Coconut milk 1 can Thai kitchen 5x140 = 700 cal, 5x14=70g fat, 15g carbs, 5g protein Potassium not listed, Goya milk 125 x 5 = 625mg potassium

Stony field whole milk yogurt 3/4 cup 150 cal, 6g fat, 20g carbs, 5g protein, 260mg potassium

Vanilla, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, pinch of salt, shredded coconut, honey, lime juice

Blueberry shake

1/2 - 3/4 cup frozen blueberries

1/3 jar of Trader Joe’s creamy peanut butter (ingredients: peanuts, salt)

1 tbsp lemon juice

1/2 cup Costco coconut clusters

Frozen spinach to the top

Stage dry in the fridge in separate blender cups (I use a bullet-style cups / blender and bought 10 bullet cups). Add liquid (milk, almond milk, water, etc) then blend.

Calories and macros per shake: 1200 cal, 95g fat, 60g carbs, 44g protein

blue 75 cal, 18g carbs, 1g protein, pb: 890 cal, 75g fat, 28g carbs 37g protein, clusters 210 cal, 20g fat, 10g carb, 4g protein, spinach 25 cal, 4g carbs, 2g protein

Pork belly with brussels sprouts:

3 pounds pork belly. Season generously with dry rub, leave overnight. Before baking, salt the skin again. Bake at 450 for an hour to crisp the skin, then turn it down to 250 for 4 hours.

Calories: 150g protein, 750g fat = 600 + 6750 = 7350 cals

3 bags brussels sprouts

3 tbsp lemon juice

4 tbsp heavy cream

1/2 cup parmesan cheese

salt and pepper

Brussels 42g protein, 5g fat, 138g carbs = 765 cal cream 22g fat = 200 cal parmesan 38g protein, 29g fat, 4g carbs = 429 cal

Total pork belly macros:

8753 calories 230g protein 806g fat 142g carbs

Pork Belly Brussels Per serving: 1250 cals 175g protein 115g fat 2g carbs

Steel cut oats

3 cups steel cut oats

12 cups liquid (4 cups cream, 4 cups goat milk, 4 cups water)

8-10 oz butter

3 cups mixed nuts

2-3 big apples (or 5-6 small ones)

1.5lbs of frozen blueberries

Vanilla extract, pinch salt

Cover top w cloves, nutmeg, and cinammon

Stir and slow cook on low in crock pot for 5 hours.

Total 10,707 cal, 862g fat, 571g carbs, 193g protein

Per serving: 1529 cal, 123g fat, 82g carbs, 28g protein

Oatmeal 1650 cal, 27g fat, 297g carbs, 54g protein

cream 3360 cal, 352g fat, 32g carbs, 8g protein

goat milk 520 cal, 32g fat, 40g carbs, 32g protein

butter 2222 cal, 251g fat, 4g protein

Mixed nuts 2400 cal, 198g fat, 72g carbs, 90g protein

apples 235 cal, 1g fat, 55g carbs, 1g protein

blueb 320 cal, 1g fat, 4g protein, 75g carbs

As in the Australian “Supernova” study by Louise Burke that tested LCHF diets in Olympic hopefuls. Although they did poorly while on the diets themselves, after being restored to a high carb diet, multiple study participants set national records, and several others notched personal bests, but this was specifically in racewalkers who don’t usually exceed 70% VO2max.

Air quality is actually surprisingly important for both mental and physical performance and quality of life.

HRV - heart rate variability. Higher is better. If you keep trends, you can tell if you’re overtraining because it will sink reliably lower than your usual average. You can measure HRV with a Polar H10 chest band or the Apple watch. I use an H10 and the EliteHRV app, which is free.

“For example, one study(11) found that when hip-flexion and hip-extension mobility were optimized in runners, there were noted improvements in running economy. Other studies(3,10,17) have found that when these same hip muscles are mobile, both economy and force production increase, especially over long running distances. Mobility may be even more important to economy in swimming than in running and cycling. For example, one study(16) found that shoulder mobility was responsible for nearly 30 percent of the performance variability in swimmers”

“Balance on one leg while keeping your gaze on something stationary. Eventually, train yourself to look at objects farther away, then progress to closing your eyes completely. Finally, stand on an unstable surface with your eyes closed. While this is a great way to train your visual and somatosensory balance systems, the small fluctuations in your balance when you’re practicing this technique (especially with your eyes closed) also train your vestibular system. My rule of thumb is to do at least five single-leg squats on each leg, eyes closed, every morning”