I was doing dating wrong my whole life, and you probably are too - Greg Clark's "The Son Also Rises"

All the rationalist shibboleths in one neat package

The Son Also Rises is the most worldview-overturning book I’ve read in the last 10 years.

I almost never see it being talked about, critically or otherwise, so I thought I’d talk about it.

If I wasn’t already steeped in the Rationalist milieu, and more or less bought into ideas like:

“Nature vs nurture isn’t even a fight, it’s 80/20.1

“Parents today are dumb and way over-investing in their kids when it doesn’t even matter for their outcomes.”2

“Education is a gigantic boondoggle that’s solely about state-funded babysitting and locking kids up in child prisons.”3

It would have been even MORE world-shaking.

The Son Also Rises has all these implications and more, and as far as I can tell, it’s tightly argued and well supported by the data, and strongly validates all those rationalist hot takes.

But more importantly, it led me to seriously rethink my dating strategy.

I was doing dating wrong, and you probably are too.

For you see, if Clark is right, the power and importance of assortative mating for your descendants’ success and thriving is *impossibly* strong.

There’s two ways to think about mating and partnering:

First, as essentially a consumption good. You’re going to be individually benefiting from the cleverness and hotness and goodness-in-bed, and whatever other traits your partner has that affect your daily quality of life and experiences. This is more or less how *I’ve* always thought of dating and partnering, and I’ve always optimized hard on basically “consumption” attributes.

But there’s a separate, more impactful measure if you plan on having kids. And if you’re utilitarian or consequentialist at all, this term dominates *by far*, because your descendants through time will necessarily touch and impact many more people than you can yourself, even if you’re extraordinary.

This is your partner’s “social competence” as Clark would call it.

This is an important distinction. It has some overlap with “consumption” attributes, but I think they differ in pretty important ways.

For example, if you’re optimizing on only your partner, you don’t care about your partner’s family quality all that much. Sure, holidays may be awkward if siblings or uncles or whoever are weird and low human capital, but it’s not going to affect your daily life and happiness all that much.

But if you buy Clark’s thesis at all, family quality is HUGELY important, in fact THE most important attribute. As in, given a choice of “hot, smart, sexually compatible, but from a bad or average family” and “less hot, less smart, less sexually compatible, but from a great family,” choose “less,” full stop, not even an argument.

Sure, genes are all that matter for your kids’ quality. But I always thought, “well, if this person in front of me is hot and smart, that’s really all that matters, because they manifestly have those genes.” Nope. Wrong!

The reason familial quality matters more than individual quality is that it’s the “true baseline” from which your kids will be drawn, and there are very meaningfully distinct baseline levels to draw from.

In other words, in any given individual, their particular genes represent a draw from a baseline, and then random chance or lucky perturbations on top of it. Regression to the mean means that your kids are likely to regress to the baseline - so if your partner is a “flower growing from a pot of dirt,” and has a lot of “lucky” components in their genotype, the good stuff is less likely to end up in your kids.

And “optimizing” inherently means you’ve made tradeoffs.

Because of how traits work in terms of “better” being “rarer,” if you’ve ended up with somebody super hot and fun and clever, it’s a good bet you’re trading off on familial quality, because few of us are outstanding enough to get the impossibly hot, brilliant Ivy grad from a rich, highly conscientious, and high performing family.

So the major change in worldview that *I* got from the book was “holy crap, I’ve been doing dating wrong this whole time!”

The things I thought were important are transitory, my partner’s phenotype isn’t as strong a signal as I thought, and optimizing towards phenotypic traits instead of familial quality is going to ultimately screw my kids and later descendants.

As the kids used to say, “big if true.”

The rest of this review will go over Clark’s arguments, and you can decide if you think it’s true, too.

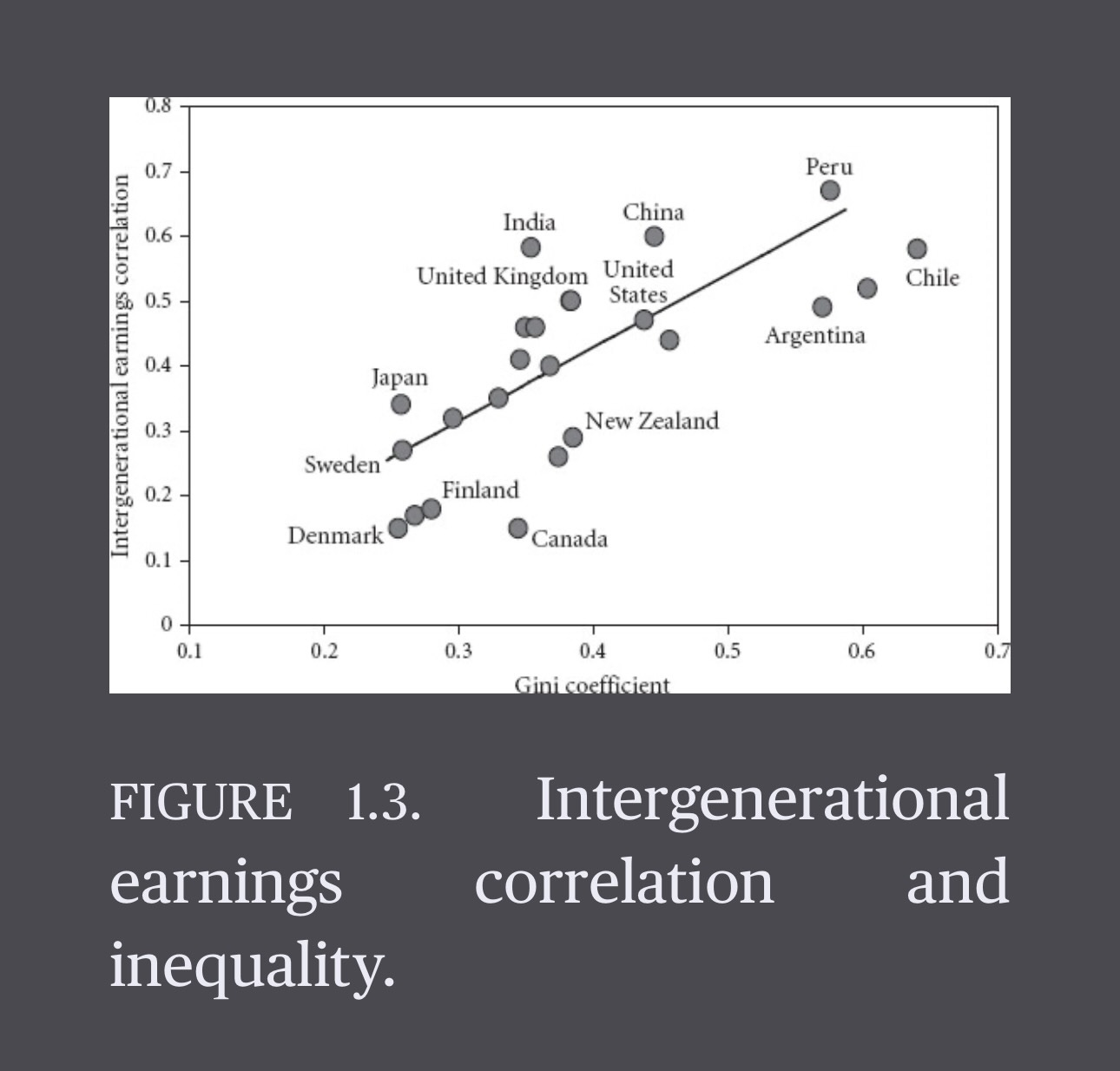

Clark is interested in social mobility and regression to the mean. One of social sciences more hopeful results is that social mobility has been getting higher as our societies have become more meritocratic. A pauper may give birth to a captain of industry, and a rich man whose kids are wastrels will see his fortune diminish to nothing.

If this were true, it would imply that social mobility and regression to the mean are both high, or conversely that “persistence rates”4 are low. The specific figure he cites have r values (persistence rates) of .15-.65.

If this were true, then any initial advantage or disadvantage would be wiped out within 3-5 generations.5 And I can envision social scientists clutching their papers showing this, tears of happiness in their eyes - “We’ve won! Nurture dominates nature! We CAN create a fairer and more equitable world!”

This is, of course, complete bullshit.

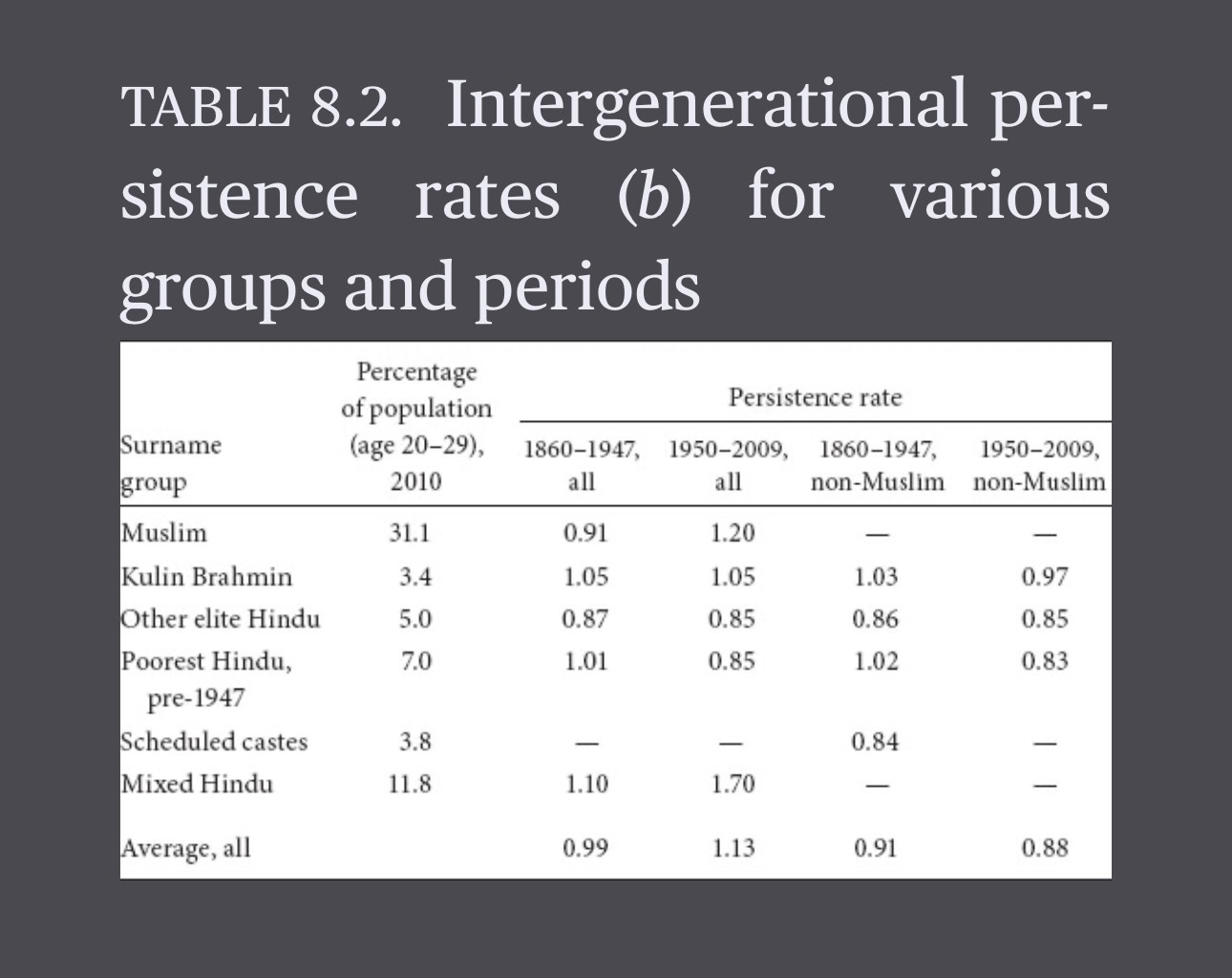

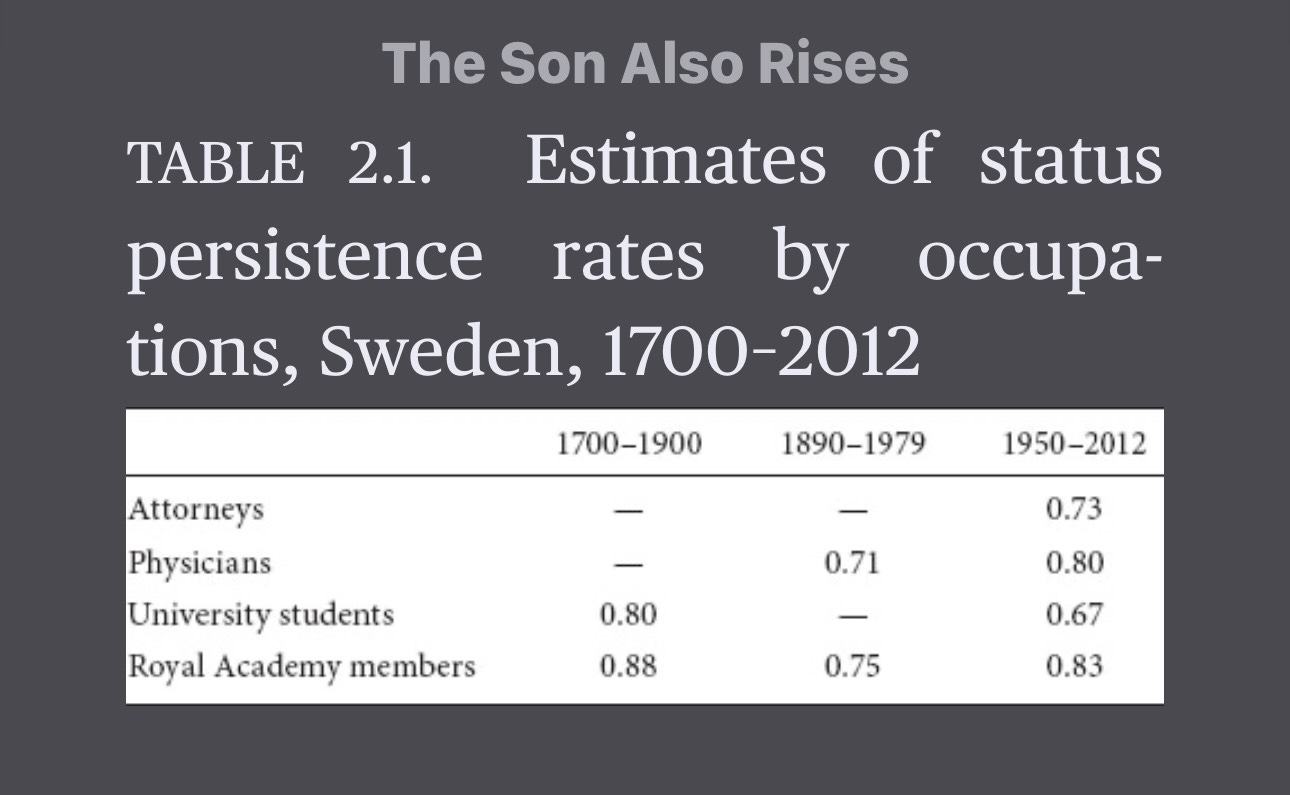

Let’s look at Sweden, of .15 correlation fame. That’s at the single-generation level. But what if you look at specific surnames over a hundred years, and follow those lineages, and look at how many times in the same lineage, people are doctors, attorneys, university students, or Royal Academy members - what persistence rate would you see?

Whew! Call me crazy, but .71-.88 sure seems a lot higher than .15!

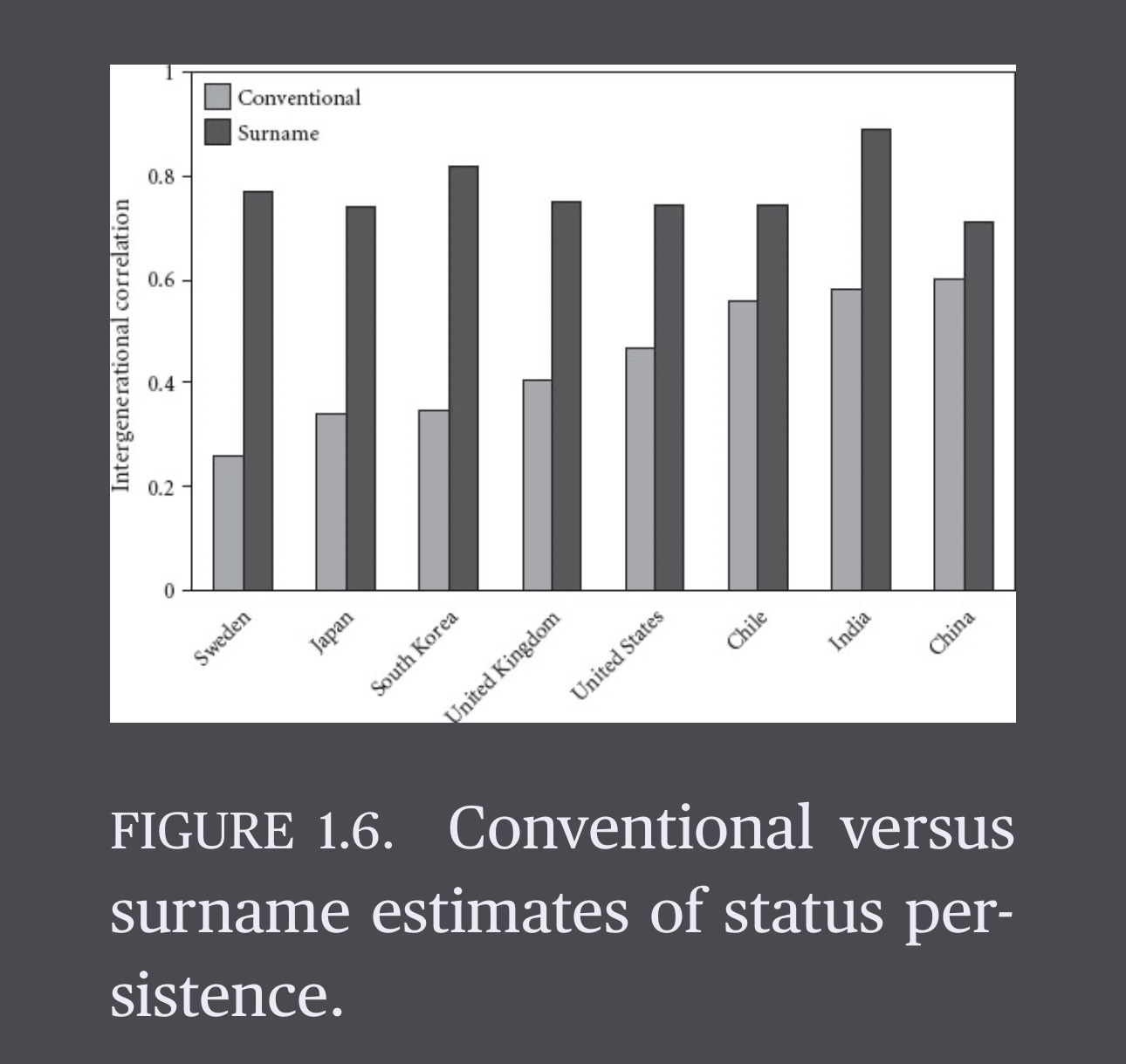

In fact, this generalizes and in every single country Clark uses the surname method, he sees much higher lineage persistence rates than conventional parent-child persistence:

This actually shouldn’t be too surprising. I mean, for one thing, just look around you - it’s likely you’re of roughly the same status as your grandparents. It’s also likely you and your siblings are roughly the same status.

But if a random die had been shaken and these familial correlations were ONLY .15-.65, you’d expect better than even odds to observe fairly different social classes even when looking around at your immediate family.

Consider the Pepyses, of Samuel Pepys6 fame. It’s a rare surname. The Pepyses emerged from obscurity in 1496 when one enrolled at Cambridge, and they’ve been high status ever since. Since then, 58 have enrolled in Oxbridge - for an average surname with the same family size, you’d expect 2-3 enrollees. Of 18 Pepyses alive in 2012, 4 are medical doctors. The 9 Pepyses that died between 2000-2012 left estates of more than $400k pounds on average, more than 5 times the average estate value. If the .15 - .65 mobility figures were actually true, the odds a family like this would maintain high status over 17 generations is vanishingly small.

And the Pepyses aren’t exceptions - they’re part of a recurring trend.

“Sir Timothy Berners-Lee, OM, KBE, FRS, FREng, FRSA, the creator of the World Wide Web, is a descendant of a family that was rich and prominent in early-nineteenth-century England. But, further, the name Berners is descended from a Norman grandee whose holdings are listed in the Domesday Book of 1086.

Sir Peter Lytton Bazalgette, the producer of the TV show Big Brother and chair of the Arts Council England, is a descendant of Louis Bazalgette, an “eighteenth-century immigrant and tailor to the prince regent—the Ralph Lauren of his age—who died, leaving considerable wealth, in 1830.

Alan Rusbridger, editor of the Guardian newspaper, that scourge of class privilege and inherited advantage, is himself the descendant of a family that achieved significant wealth and social position in Queen Victoria’s time. Rusbridger’s great-great-grandfather was land steward to His Grace the Duke of Richmond. The value of his personal estate at his death in 1850 was £12,000, a considerable sum at a time when four of every five people died with an estate worth less than £5.”

Or, my absolute favorite example - the persistence of Norman eliteness in England.

Roughly a thousand years ago, in 1066, the death of Edward the Confessor led to a 3-way battle royale for the English throne between Harold Godwinson (Earl of Wessex), Harold Hardrada of Norway, and William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy.

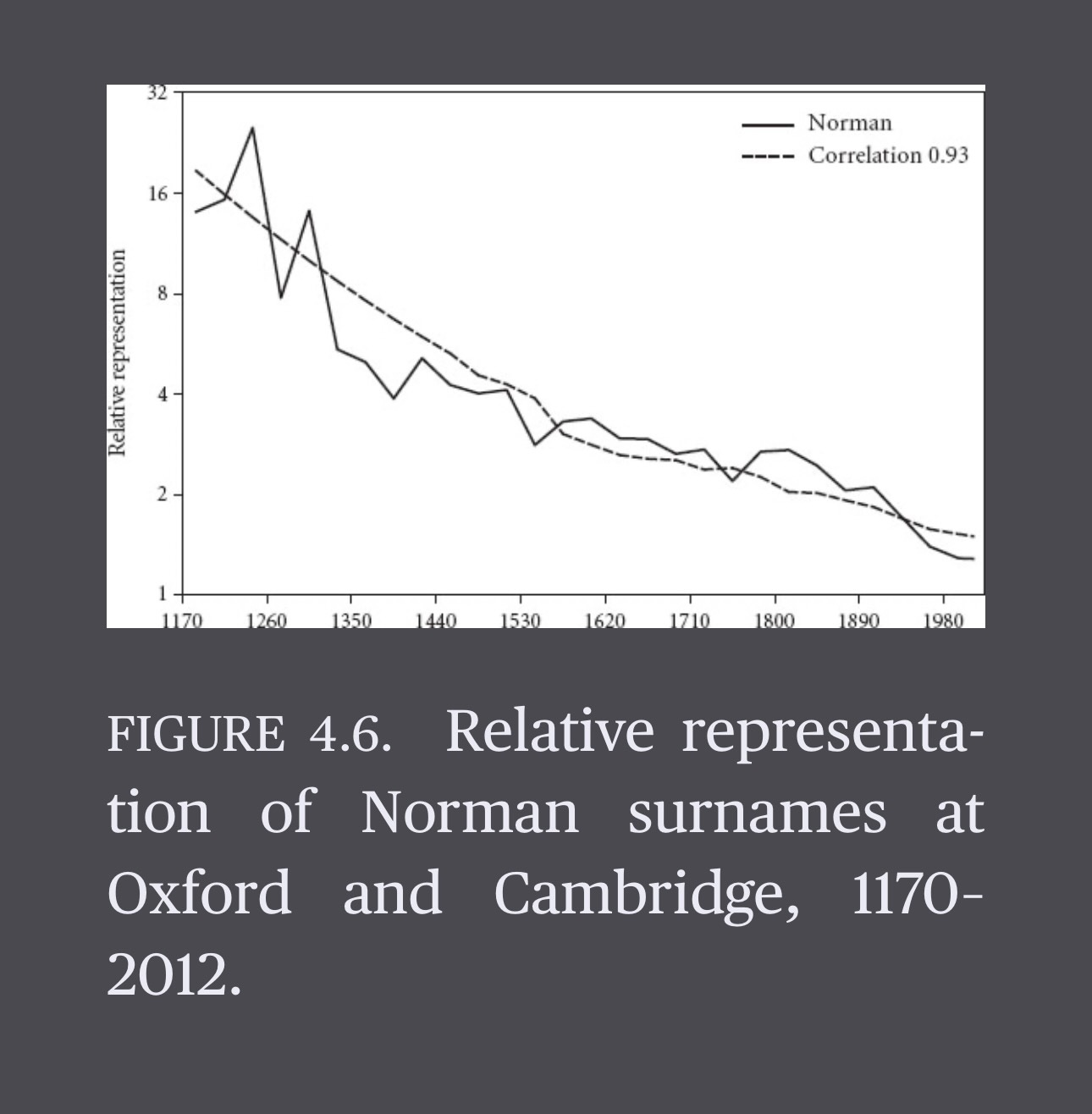

After Godwinson fought off Hardrada in the East, culminating in the Battle of Stamford Bridge,7 William the Conqueror invaded in the south with an army he raised in Normandy and the rest of France, and Godwinson had to rush down to meet him. William and the Normans won. They installed a new “elite” in England, and now, nearly a thousand years later, the descendants of that Norman elite are still disproportionately likely to get into Oxbridge:

Quality will out.

In other words, Clark is arguing that “quality will out.” He calls this quality “social competence:”

“The problem arises when we try to use these estimates of mobility rates for individual characteristics to predict what happens over long periods to the general social status of families. Families turn out to have a general social competence or ability that underlies partial measures of status such as income, education, and occupation. These partial measures are linked to this underlying, not directly observed, social competence only with substantial random components.”

And what does it mean if “social competence” and something like “familial quality” actually exist?

“Underlying or overall social mobility rates are much lower than those typically estimated by sociologists or economists. The intergenerational correlation in all the societies for which we construct surname estimates—medieval England, modern England, the United States, India, Japan, Korea, China, Taiwan, Chile, and even egalitarian Sweden—is between 0.7 and 0.9, much higher than conventionally estimated. Social status is inherited as strongly as any biological trait, such as height.”

So, what’s going on?

Did those silly social scientists measuring .15 parent-child income correlations mess up the math?

Well, the Replication Crisis IS a thing, so we should always be ready to cast a skeptical eye on any results - but these are widely measured results and it’s not that. What’s happening is that one-generation studies of social mobility are subject to a lot of noise, and usually only measure one endpoint, like income or educational attainment.

But Clark’s “social competence” is linked to all potential endpoints - education, income, wealth, occupation - with random perturbations.

And people make tradeoffs. They may choose to be professors instead of executives, or physicists instead of quants - there goes “income” as a metric. Gates and Zuckerberg are both dropouts - hope your endpoint isn’t “educational attainment,” because they’re failures by that metric.

Individual attainment also has “luck” components both in their endowment of innate capabilities and in their life choices - did they pursue a more or less lucrative career, did they just make the bubble and get admitted into an Ivy versus just missing out, and so on.

Clark is positing a “status genotype” in a lineage and one-generation mobility studies only observe the phenotype of one particular individual in that lineage, and often only one aspect of their overall phenotype.

This is why Clark is studying and measuring surname mobility, to infer an entire lineage’s “social competence.”

And he finds that it exists, that you can measure it in top and bottom quintiles equally, that it’s Markov, and that the persistence rate over n generations is “persistence rate”^n.

“Indeed, this book suggests, based on these characteristics, a social law: there is a universal constant of intergenerational correlation of 0.75, from which deviations are rare and predictable.”

Not only this, but at the forty thousand foot view Clark is taking, essentially all the Western social welfare, educational, and affirmative action interventions the last hundred years have been entirely pointless, if you assume the trillions of dollars spent on them should be making things more egalitarian and increasing social mobility overall.

Consider education.

In multiple countries, Clark tracks persistence rates (the rate at which elite or lower class families “persist” or fail to regress to the mean) both before and after universal education rollouts. There is no change in persistence rates from education.

Clark compares Sweden, the UK, and the USA, with educational systems ranging from “fully state funded even at the college level” to regimes where private education is increasingly more prevalent among high status parents in the UK and USA. But does it actually boot the parents spending $45k a year at private schools in the USA? It does not - it neither slows regression to the mean nor ensures higher status for that generation of children.

There are also essentially no changes in persistence rate across very significant social and educational changes. In Sweden and the UK, moving to state funded, high quality schools being free to everyone of any status caused no change in persistence rates. The persistence rates stayed doggedly on their hundred-plus-years trend.

“Counterintuitively, the arrival of free public education in the late nineteenth century and the reduction of nepotism in government, education, and private firms have not increased social mobility. Nor is there any sign that modern economic growth has done so.”

Education does not create social mobility, it’s mostly pointless.

Nor has expanding the franchise of voting, nor progressive taxation, nor any of the social welfare and safety net programs in Western countries. Just think of that! How many trillions of dollars are spent on state-funded education in the West? How much agonizing and debate and funding battles go on every single year? It’s all arguing about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin.

All just noise. Sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Genes, as always, are destiny.

“these data do not imply that outcomes happen to people solely because of their family background. Those who achieve high status in any society do so because of their abilities, their efforts, and their resilience in the face of obstacles and failures. Our findings do suggest, however, that we can predict strongly, based on family background, who is likely to have the compulsion to strive and the talent to prosper.”

Another interesting implication? Bryan Caplan is right.

Another interesting result if Clark is right about genetically transmitted “social competence” - we’d see no difference in large families versus small families, because the disproportionate investment the smaller families achieve into their fewer children *doesn’t actually matter.* And indeed, Clark finds this!

In 1880-1990, the rich in England consistently had fewer children than the poor. This should have enabled them to invest more time and effort AND wealth into their children, by dividing those resources amongst fewer kids. With all this extra attention and wealth and legs up, wouldn’t we expect them to have higher persistence rates, or even move further up above the mean? They don’t.

They don’t, because education doesn’t matter, and for the most part, the extraordinary individual attention and effort parents put into their kids doesn’t really matter.

There’s a direct test, too - the rich in England in the time period before then, in 1500-1800, had more children than the poor. Yet these two very different fertility regimes showed no difference in social mobility rates for the rich in England. Persistence rates were the same before and after the Industrial Revolution, and happened regardless of family size. Bryan Caplan is right.

What is happening here? If everything is innate and driven by genetics, why does regression to the mean happen at all?

In Clark’s words, the regression is driven by leaks in assortative mating.

“That mechanism is the intermarriage of the children of rich and educated lineages with successful, upwardly mobile children of poor and uneducated lineages. “Even though there is strong assortative mating—because this is based on the social phenotype created in part by luck—those of higher-than-average innate talent tend to mate with those of lesser ability and regress to the mean. Similarly, those of lower-than-average innate talent tend to marry unlucky offspring of higher average innate talent.”

“You’re like a flower that grew out of a pot of dirt.”

This is handily characterized by the Simpsons episode (S6E19) where Lisa almost marries Hugh, who she meets at Oxbridge. He, a scion from a noble line, with a family estate and a deep lineage. Lisa, a Simpson.

In other words, assortative mating is LITERALLY the most important thing to your descendants’ success. And not at the individual level, at the lineage level. That gap between “.15” and “.75?” That gap is the importance of getting assortative mating right, and optimizing on familial quality vs individual quality.

Looking at parents isn’t enough - we see this because even controlling for parents’ status, grandparent and great-grandparent status is still predictive of status.8 The correlation for great-grandparents’ status with their great-grandchildren is 3x stronger than predicted! (.24 actual vs .08 naively predicted).

“What is the significance of these results for parents socially ambitious for their children? The practical implication is that if you want to maximize your children’s chances, you need to pay attention not to the social phenotype of your marriage partner but instead to his or her status genotype.”

Those smart hotties with everything going for them, but from undistinguished families? Literal poison, hellbent on driving your children and later descendants to poverty and ruin.

Well, that’s a bit hyperbolic. But you know, the gestalt is gesturing in that direction. Your kids are a lot more likely to regress to the mean, and to do so harder, than if you chose a merely average person, but from a good family.

And as we saw with education - there’s no social interventions that work at this level. The only thing that can really move that needle are things that affect the rate of intermarriage between levels of the social hierarchy, and between ethnic and religious groups.

Tinder has almost certainly done massively more for actual “equity” and social competence redistribution than all the trillions spent on education in the last 100 years!

So if you want to actually impact inequality, spend your time creating dating apps for hot lower class women to date educated men with money, because that’s the only thing that will move the needle. I’d suggest making one for the vice versa, but educated women with money are too smart to fall for that.

One interesting test of whether it is indeed “assortative mating leakage” is India.

So if it’s all genetics and “assortative mating leakage” is the true source of regression to the mean, India should be a great test case, right? After all, the caste system has been incredibly well adhered to, and has created a potpourri of genetically distinct populations delineated by caste that go back thousands of years.9

And indeed, you would be right! Not only is persistence rate higher in India when looking at castes, there are multiple groups who are not regressing to the mean at all, but are further differentiating from the general population. In other words, their persistence rate is actually greater than 1!

If you go back and look at “relative representation” by caste in elite jobs, you see extraordinarily flat trends going back ~150 years.

The “scheduled caste” trendline is an interesting story - it shows that thumbs on the scale can indeed work in some cases. Broadly, the British defined some “scheduled castes” before they left, rather sloppily, and those castes were given affirmative action for various desirable jobs like physician, attorney, police sergeant, etc after independence in 1947.

Clark tells us that the castes were defined sloppily enough that there were a number of castes in the larger scheduled group that didn’t really have any disadvantages, and it is they who have prospered in this regime of affirmative action. I found it interesting as one case where a government intervention really moved the needle on social mobility, though, unlike education, welfare or social safety nets, and much else.

Clark’s contention is that the castes prospering now weren’t really disadvantaged to begin with - but maybe there’s some way to identify populations like that and target affirmative action more intelligently?

But let’s look at what Clark is doing, shall we?

I’ve been teasing graphs here and there, but Clark is assembling a formidable story that looks in multiple countries in the world with huge differences in social, political, and cultural baselines, to test his hypothesis.

If you wanted to look at status for a given lineage back 5, 10, 20 generations or more, how would you do it?

Clark focuses on rare surnames. Surnames because that’s how you can trace a lineage for many generations - rare because you can be more sure of the lineage you are tracing, and because more common surnames are more easily subject to noise and records mistakes. Rare surnames have another advantage too - you can get a cleaner read on their population incidence in various time periods, and thus have a cleaner read of any over-representation in occupations like doctors or lawyers, or in graduate degrees and income bands and other metrics. This is an important part of Clark’s methodology, because measuring “eliteness” over hundreds of years can be a difficult task, and you want the cleanest and most legible signals to make the comparison simpler and like-to-like.

But more importantly, I think, is to look at these conclusions with a skeptical eye, to try to suss out if there’s enough wrong with the methodology that we should reject Clark’s conclusions overall.

After all, it would be a LOT more convenient if education actually DID do anything, if we COULD date hotties from bad families, and if we weren’t all probabilistically consigned to essentially the same status as our grandparents and great-grandparents.

Methodology weaknesses.

First, what about name changes?

People change their surnames all the time - and there’s almost certainly upward biases, where people are more likely to leave “known lower class” surnames and adopt “perceived elite” surnames, right?

Broadly, in several of the countries Clark looks at, name changes in general, or name changes adopting elite names, are explicitly illegal for much of the period being considered.

In Sweden, the Names Adoption Act of 1901 forbade anyone else adopting noble names. There is also a Naming Law of 1982 which requires approval from the Swedish Tax Agency for any surname changes.

In Japan, by 1898 surnames were strictly hereditary, and the Family Registration Act of 1947 established that only the head of the family could apply for a surname change, and they would only be granted in cases of “unavoidable reasons.”

He also looks at “rare” surnames in particular in many cases, for cleaner signals and to mitigate some of the problems inherent in looking at common names (China, for example, has only ~4,000 surnames for it’s 1.1B people).

Another check Clark does is look at the incidence of these names in the population, which he does to gauge over-representation, but also serves as a control on whether this is happening to any significant degree. The proportion is the same looking at “male deaths from 1901-2009” and “male births from 1810 to 1989.”

Finally, he points out that in nearly all cases, lower classes adopting upper class names will serve to move persistence rates further down - that is, the observed rates are a lower bound if lower-class name changes to the names-being-measured are common.

He’s looking at surnames and following distinct lineages? So what, like a handful of ”n” per country? That’s obviously not a good sample, you can’t infer anything from that!

Actually, he bundles together a lot of surnames for all of his cuts. The smallest I see him get (besides talking about individual families like the Pepyses or the Darwins), is 13 rare surnames who passed the highest imperial administration exam in China in the Qing dynasty.

But he often has sample sizes of many tens of thousands. His names used for Ashkenazi include: Cohen, Goldberg, Goldman, Goldstein, Katz, Lewin, Levin, Rabinowitz (and variants), and who totalled 300k.

For Kulin Brahmin: Bandopadhyaya/Banerjee, Bhattacharya/Bhattacharjee, Chakraborty/Chakravarty, Chattopadhyaya/Chatterjee, Gangopadhyaya/Ganguly, Goswami/Gosain, and Mukhopadhyaya/Mukherjee, and are 3.4% of the population in Bengal

And so on.

What about adoption?

What about adoption to continue the male line when a family has no male heirs? Isn’t that a big thing in Japan? Since people are choosing proven-successful men for their adoptees, wouldn’t this skew the persistence rate up?

Yes, it would. Clark finds evidence that such adoption might be up to 10% of male descendants of high status families in Japan. But even assuming they were 25%, it would only bring the persistence rate up .06. Since it’s at .72, the most it would drop to is .66, the same as in Taiwan, and still much higher than single-generation estimates.

Similarly, Japan is likely an outlier in this regard - but even if the same proportion of adoption were going on in the other countries measured, it would still be telling essentially the same story in terms of persistence rates.

He sure looks at doctors a lot, maybe there’s something funny with how “doctoring” is defined, or with doctor occupational status over the years?

Clark had an argument about doctors being an ideal test case, because it’s a selective occupation and always has been, has centralized medical registers listing who is a doctor in a given country, and it’s generally easier to figure out what fraction of the population are doctors, to determine over-representation.

But Clark also looks at professors, attorneys, police sergeants and subinspectors, Oxbridge admittees, people attaining graduate degrees, corporate managers, academic authors, medical researchers, income deciles, and much else, and finds the same trends at roughly the same strengths.

In the case of the Darwin / Keynes and some other individual families, he also looks at how many have Wikipedia entries or obituaries published in papers of record like the Times to estimate modern era prominence.

Maybe it has to do with only looking at elites?

He looks at much more than elites. Indeed, he’s at pains to point out that you can see these much stronger persistence rates if you divide a population up by ANY grouping other than parent-child, because the parent-child persistence is prone to so much more noise.

But you can divide by religion, ethnicity, or other groupings and find the same much larger over-represententation and persistence rates:

Sometimes he assumes the population incidence of surname collections between recent dates and past dates are the same.

How could this go wrong? If elites are more fertile than commoners, they will become a greater proportion over time, and then their over-representation as doctors is normal.

However the trend is usually in the other direction - elites typically have lower fertility, particularly post 1800 (samurai had 4.54 descendants on average compared to 4.78 for commoners in the mid 1800’s, English elites post 1800 have lower fertility than commoners). The counter example, English rare surname elites between 1500-1800, and Ashkenazi before 1900, were able to have their actual pop incidence tracked via censuses and record keeping for the comparisons used.

He also directly considers a case where this happens - the surname Loveridge underwent a steep decline in persistence rate. It also had extraordinary growth in England between 1881-2002. What was happening was that a high fertility lower class group with that surname, Gypsy and Travelver families, had higher fertility and were diluting the Loveridge overall persistence rate. The trend will go down until the mean is low enough that regression to the mean is balanced by the excess fertility.

Clark actually highlights this example as an example of how underclasses persist:

“another explanation for long-lasting underclasses in a society, even with intermarriage between the underclass and the rest of the population, is that the underclass has much higher fertility rates than the society as a whole. The effects of marital exogamy in pulling the group towards the mean are offset by the higher fertility of poorer members of the group.”

Overall, of course, Clark is looking at old records over hundreds of years in multiple countries - there’s a lot of “garden of forking paths” decisions he could have theoretically made to bend things towards his desired conclusions. But as far as I can tell, he decided on his methodology and applied it consistently, and consistently found much higher persistence rates than naive parent-child ones all over the world.10

His conclusions are also dovetailing into things that we know are supported from other evidential bodies - Caplan’s contentions around parenting importance, how no amount of educational spending increases test scores in aggregate, and so on.

As he points out in the book, this also aligns with our own experiences and observations - if I look around, I see MUCH higher “persistence” in status in families than .15, or even .5.

What are some other implications?

There are so many implications.

Assortative mating must be IMPOSSIBLY rigorously adhered to historically, for effects like the 900+ year Norman Oxbridge over-representation, and for Kulin Brahmin over-representation to still be persisting after 3000 years of potential leakage.11

All those arriviste rich American upstarts marrying into British and European nobility were *actually right* and following optimal descendant strategy™

If you actually care about inequality, and / or raising your entire society’s “social competence,” you should be doing whatever you can to get people to date and have kids between social classes, at scale. So what would actually move the needle?

Socially normalizing rich + educated men having mistresses and / or multiple wives12

Incentives for rich + educated men to have more kids, like child support caps, state-funded child support, or decreases in tax rates the more kids you have

Creating “sugar baby” dating apps

Running GWAS studies on high vs low and average social competence lineages, so we can start narrowing in on the genetic components and ultimately make them available for embryo selection

Stop assuming social or political interventions aimed at “inequality” or “social mobility” actually do anything besides wasting trillions of dollars

That money would be MUCH better spent on the GWAS’s and embryo selection / gengineering labs and lobbying if you wanted to actually move the needle on aggregate social competence

So what can we do?

Ultimately, if you buy the overall picture Clark is painting, I think it has a few actionable takeaways for the individual.

Prioritize familial quality over everything else when dating.

Somehow convince your kids to ALSO prioritize familial quality over everything else when dating, and to convince THEIR kids, etc.13

Stop approving increases in school funding, it’s all a pointless boondoggle.

Stop having so few kids and overinvesting in them, but instead do as Caplan suggests in Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids, and have more kids with less investment.

To points 3 and 4, I’ll close on one of the passages from the book. Clark seemingly has a bee in his bonnet about upper class Manhattanites spending hundreds of thousands on exclusive preschools and private schools and tutors. In one of several passages where he talks about it, he points out that his inexorable logic shows them to be wrong, too:

“There is strong persistence of status, but those at the top of the social hierarchy in societies such as the United Kingdom, the United States, and Sweden will inevitably see their children, on average, move down.

Further, the rate of regression downward to the mean is the same for the upper echelons of society, despite their considerable investments in their children, as is the rate of upward mobility for the lower echelons, even the ones who don’t bother to turn up for the PTA meetings.

The forces of regression to the mean may seem glacially slow from the point of view of those at the bottom of the social ladder. But for the elites of Manhattan, Greenwich, or Silicon Valley, these forces exercise a death grip on dynastic ambitions. These are people used to getting what they want. Why should they be frustrated in this one primal ambition, for their children to enjoy the same rewards in life as their parents?”

“This is all consistent with the idea that once parental inputs to children reach a certain basic level, which does not include Baby Einstein toys, playing Mozart to babies in the womb, or sending them to the Dalton School, parents can do nothing to improve outcomes for children.”

“Is there anything that this book can say to people who want the best possible income, wealth, education, and health “outcomes for their children? The one scientific contribution we can make is to point out that with the appropriate choice of mates, a family can avoid downward mobility forever.”

And what are the stakes? What can you get if you do it right? I mean, in the limits Kulin Brahmins in India have been doing it successfully for something like 3,000+ years!

But you probably won’t be able to reorganize all of future society to make sure your great-great-grandkids and all their potential mates take familial quality seriously enough to breed as tightly as the Indian caste system.

No, instead you’ll probably ONLY be able to make your line elite for 600+ years:

“This implies that if the rate of persistence is indeed 0.75 or higher, families observed at any time in the elite spend twenty or more generations (six hundred years) at above-average status. The same holds for families observed at low status: they typically linger at below-average status for twenty generations or more. A high persistence rate implies very slow regression back to the mean; it also implies the persistence of some families above or below the social mean for astonishingly long periods.”

You want the high level summary?

Polderman 2015, a meta-analysis of all twin studies that looked at identical, dizygotic, and adoptees to derive the following heritability figures:

https://imgur.com/gJW4ehm

https://imgur.com/a/yjIWYnT

And the 20% “nurture” part isn’t parenting, it’s peers.

Thank you Bryan Caplan (Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids) and Judith Rich Harris (The Nurture Assumption)

Aww, now maybe that’s not fairly painting the full “educational system” picture. After all, it’s ALSO the nation’s biggest jobs program for authoritarian mid-wits.

Persistence rate is the degree to which familial status is correlated with descendant’s status. So a persistence rate of .15 would represent .85 regression to the mean.

Indeed, Clark relates how “in the early stages of the research, I gave sunnily optimistic talks about the speed and completeness of social mobility. Only when confronted with evidence of the persistence of status over five hundred years that was too glaring to ignore was I forced to abandon my cheery assurance that one of the joys of the capitalist economy was its pervasive and rapid social mobility.”

First secretary of the English Admiralty, member of Parliament, and noted diarist

Which I have a soft spot for because it features the unnamed and impossibly metal Berserker of Stamford Bridge, where a Norwegian viking with a giant axe held off the entire English Army singlehandedly, cutting down more than 40 English soldiers in his valiant last stand.

Long and Ferrie (2013); Lindahl et al. (2012); Boserup et al (2013)

From David Reich’s epic paper Reconstructing Indian Population History

In fact, he relates in the preface how he started off optimistic and believing that social mobility WAS high.

“Thus, in the early stages of the research, I gave sunnily optimistic talks about the speed and completeness of social mobility. Only when confronted with evidence of the persistence of status over five hundred years that was too glaring to ignore was I forced to abandon my cheery assurance that one of the joys of the capitalist economy was its pervasive and rapid social mobility.”

"Having for years poured scorn on my colleagues in sociology for their obsessions with such illusory categories as class, I now had evidence that individuals’ life chances were predictable not just from the status of their parents but from that of their great-great-great grandparents. Indeed there seems to be an inescapable inherited substrate, looking suspiciously like social class, that underlies the outcomes for all individuals. This book is the product not of acute intelligence but of muddling through to a conclusion that should have been obvious to anyone who looked.”

Another example of extremely strict assortative mating is Japanese samurai:

“If samurai descendants never intermarried with descendants of commoners, then, assuming the same fertility, their descendants would now constitute 5 percent of the population. But figure 10.3 suggests that samurai descendants may be as “much as ten times overrepresented among modern Japanese elites. That rate implies that half the modern elites are descended from the samurai. Intermarriage would greatly expand the share of the modern population of samurai descent. But if the samurai are really ten times overrepresented in modern elites, intermarriage must have been limited, so that their descendants constitute no more than 10 percent of the modern population.”

So over hundreds of years, the most leakage was an additional 5% vs platonically endogamous assortative mating - pretty impressive.

My favorite policy idea on this front is “for every year that you’ve paid >$100k in taxes, you can legally marry another wife.” This makes it a very legible status signal, for both the man and the woman. If you and wife #2 and #3 are out with hubby, it’s like rolling up in the Lambo, but inside the store / restaurant / club / wherever - and both men and women like to be seen in the Lambo.

I actually have some ideas on this one - you can’t do “marriage conditions” with wills as much these days due to some bad precedents, but you CAN appoint trustees who follow certain criteria on whether to disburse trust funds! But you know, talk to your lawyer, this is not legal or financial advice, etc.

Came here from the genetic engineering post. Long comment incoming, but skip to the end for the TLDR if it gets boring.

My understanding of heritability, and what causes regression to the mean seems to be different than yours, and leads to different conclusions about the importance of family background, vs. the importance of individual genetics. Although I'm a layman so it could very well be my incorrect understanding (and I ideologically lean towards individual over group identity/relevance so that could make me biased).

Here's my understanding;

Regression to the mean, especially for traits influenced by a large number of genes, occurs regardless of ancestry. Even with two high-IQ parents, their child’s genetic makeup is likely to regress toward the population average.

Hypothetically, if there were 100 important IQ-related genes, with the average person having 50 positive genes, the top 1% of children (assuming random 50/50 inheritance) would have about 62 positive genes. If two individuals from this top 1% were paired, their child would have a 50% chance of inheriting each gene from each parent. The child’s expected number of positive genes would remain 62 if the parents had identical positive genes.

However, if the overlap between the parents’ 62 positive genes is only 50% (31 shared genes, 31 unique genes), the child is guaranteed only to inherit those 31 shared genes. For the remaining 31 unique genes from each parent, the child inherits each with a 50% probability. This increases the variance in the child’s gene count around the expected value of 62.

In reality, since there are way more than 100 IQ producing genes (and possibly the result of Epistasis, multiple genes which together create an effect, but alone are neutral. This would have worse than 50/50 inheritance odds), the regression to the mean would be stronger than assuming just a 50/50 inheritance. If parent A had a combination of 2 genes that together produced higher IQ, and parent B didn't overlap with those two genes (with their high IQ deriving from somewhere else), the child would have to win the genetic lottery twice in order to benefit. Making the actual heritability of that single-parent IQ gene pair at 25%. Since the pool of IQ-enhancing genes (and gene combinations) is small compared to the vast number of neutral or non-IQ-affecting genes and gene combinations there’s more room for downward variation than upward. This asymmetry makes larger losses in positive IQ genes more likely than small gains.

Now when it comes to how I understand this would apply to lineage;

On the same hypothetical shown above, when two parents have 62 random IQ producing genes or gene combinations that are independent of each other, the expected mean of offspring would depend on how much overlap there is. If parent A has an IQ gene pair that parent B does not have, the child will have to get lucky for each gene, so 1/2 times the number of different genes that contribute to that one IQ effect. If it was 2 genes, each with 50% heritability, then the chance of a child inheriting those IQ genes would be only 25%, while it would be 100% if the parents shared the same mutation.

Larger losses would be more likely than lesser gains, as the space of IQ increasing genes decreases the higher IQ you are, and the space of normal IQ genes increases, causing regression to the mean. However, if you assume that the 62 positive genes are not randomly selected, but are somewhat dependent on each other, or on some 3rd factor (like for example, shared ancestry with lots of intermarriage), then the overlaps (and hence guaranteed inheritance) of those 62 genes and gene pairs would be expected to be a lot higher! Therefore, there would be a higher chance of heritability of IQ (and other heritable factors) when you concentrate the blood a bit.

Of course the heritability of clusters of genes is not completely random, but where IQ is derived from combinations of genes that aren't clustered, there would be a meaningful advantage to having more overlap among IQ producing genes. Shared lineage would increase the likelihood of that overlap.

Essentially, (at least as I understand it) the lineage shouldn't matter for the likely IQ of your children with someone, unless there is significant shared lineage or shared concentration of IQ genes. Person A with high IQ Japanese familial lineage marrying Person B with high IQ New England WASP lineage will have the same mean expected mean IQ, and same downward variance, as either of them marrying an equivalent high-IQ prole. Unfortunately, this would mean there's literally no way to benefit from the advantages of lineage-IQ, unless you're already part of such a lineage, or otherwise have access to a closely genetically related person who's also benefited from at least a couple of generations of traditional non-lineage assortive mating.

Darwin married his cousin after all, and I’d imagine the high-IQ families Clark describes originated from a small, genetically distinct group—whether an invader stock or a semi-legendary aristocracy. These families likely intermarried mostly exclusively, concentrating their advantageous “blue blood,” so to speak. This would explain the persistence of high IQ among elite families without suggesting that someone should specifically target high-IQ lineage unless that lineage is closely related to their own.

This concentration of lineage may also increase the risk of genetic diseases and single genes that cause significant IQ deficits. While such outcomes were likely managed by ensuring those with severe issues did not reproduce—either through exclusion, disinheritance, or marriage outside the lineage—the negative effects of inbreeding were still present. Over time, these risks may have been outweighed by the positive effects of preserving and reinforcing high-IQ genes within the lineage.

Cultural practices may have helped mitigate some of the downsides of inbreeding. For example, in aristocratic families, it was common to send non-heirs into the clergy, where celibacy may have acted as a release valve for those with undesirable traits or unlucky genetic inheritance. This practice may have reduced the reproductive impact of deleterious genes.

Anecdotally, examples like that Kennedy sister (her name I don't remember)—who was lobotomized and institutionalized due to developmental issues—many indicate elite families may have overrepresented genetic diseases. I've read this was quite common among the elite, but I have no real data.

TLDR: My understanding is that familial IQ only matters if you’re already part of a high-IQ lineage or have close IQ relatives you can marry. Otherwise, building a long-term high-IQ lineage requires either genetic testing (to find someone who shares the most positive genes with you, though this is practically impossible without a centralized database) or setting up your descendants to intermarry within the family. This might only work if you come from a unique, relatively unmixed genetic stock (e.g., Iceland, the Sámi, Japan). For most people, especially those from settler states like America, targeting familial IQ wouldn't be feasible.

If I were trying to create a long-term genetic winner lineage (a goal I personally resonate with but am not focusing on right now), I’d prioritize finding a high-IQ, accomplished woman who shares that goal. The current best approach would likely involve IVF, embryo selection, and possibly surrogacy, though there are trade-offs (I've read suboptimal gestation conditions from surrogacy can offset genetic advantages). Passing down these values and philosophies to your children is probably the key so they continue the trend over multiple generations. Gwern’s excellent piece on this topic is worth reading for what the possible future developments would look like, but I am sure you've already seen it: https://gwern.net/embryo-selection

Alternatively, you could bypass the need for a partner who shares your goals. You could find a high-IQ egg donor and raising 5+ children with surrogates. You wouldn’t need your partner to be ideal—just supportive or ambivalent (allowing you also to select for other non-trivial traits, like attraction and emotional compatibility). Finding high-IQ egg donors isn’t impossible, as shown by the Hwang affair, where researchers donated eggs for his cloning experiments despite the dubious nature of his work: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ett_8wLJ87U

Success is largely heritable, but a targeted environment can amplify those advantages. The Polgar Sisters, raised by a father who believed genius could be nurtured through environment: https://slatestarcodex.com/2017/07/31/book-review-raise-a-genius/ Coincidentally the English translation was sponsored by SSC readers: https://slatestarcodex.com/Stuff/genius.pdf

I’d appreciate your thoughts here, as I agree with your goals but understand heritability differently (and an incorrect understand would have very material effects on my own approach to my descendants). As for why, I believe that intelligence, creativity, and ability thresholds for productivity are rising rapidly. 1,000 years ago, almost anyone could farm; 100 years ago, industrialization favored the systems-makers; 20 years ago, controlling information became key with the internet; each of these setting the minimum necessary intelligence to produce something valuable much higher, and in 10 years, AI may eliminate 95% of low-performing white-collar jobs. If descendants don’t rank among the top 1% performers of the top 1% most difficult jobs, they will probably end up at the mercy of AI, the oligarchs controlling it or government-controlled UBI.

Edit: Made changes for clarity of my thoughts. After writing that out it may warrant writing a more formatted and edited post instead of just a comment.

Hm. I mean, I'm also already sold on the education doesn't do anything and nature is 80% bit too. But I find your life philosophy truly strange. Also, I've been an egg donor, and the sophisticated clinics absolutely know all this, because when you submit all your information and go through all the genetic tests, the potential recipients who are searching for a donor don't just want to know about you, they want to know about your parents, grandparents, siblings, and sometimes even cousins. So yeah, they're shopping on a family, not just a person, genericslly.

But in their case it makes sense, since they are literally shopping for gametes in a catalog from total strangers that they won't have to live with or ever even meet, so might as well select whatever they think is "the best". But I can't understand literally changing your own life strategy and making yourself less happy for some entirely hypothetical future people long after you're dead and an assumption they you'll help their status be a few percentage points higher than it would be otherwise. All genes get remixed so many times over the generations that there's basically no difference between your own descendants and those of any of your relatives once you get past a couple generations, and why do you care about an unknown person you'll never know and hypothetical future, more than your own very concrete current wellbeing anyway?? You don't have to answer or justify your values, I just think it's odd.

Came here more to point out that the fact that virtually all societies had bastard laws up until about the 20th century seems to throw a big wrench in this. Most of history elite men were absolutely free to knock up as many women as they could get away with, and those children were not permitted to take their family name and had zero legal rights to recognition of paternity. So of course those elite men reserved only the highest status woman they could bag to be the one who would have children who carried on their name. But their dispersing their genes through lower status families doesn't seem to have done much to drag them up, and we'd have no way of knowing anyway. The other thing is that you focus here on elite men using exactly this method ,and yet they always have and just reserved the assortative mating to their legally recognized marriage and children. Plus intelligence is more heritable from the maternal line than the paternal, especially for boys who cannot get any of the cognition genes located on the X from their dad. So the maternal line being smart is likely more important than the other way around, though I suppose that might even explain why having a bunch of low class bastards doesn't change much, since really it's the high class maternal line that's more of the persistent lineage (especially for males).