Recovery after workouts

With healthy doses of Renaissance Periodization and Dr. Mike Israetel's wisdom

Recovery is the single most important + neglected area of training I see out there among otherwise disciplined athletes.

Diet? People are on top of it. Getting the right workout intensity? Most people nail it. Getting frequency, specific lifts, and HIIT right? More often than not, yeah!

But I will often see an athlete worrying about something far in the decimals of optimization - nutrient timing, or worrying about more than 8g / kg carb loading, or accessory volume, and all while cutting sleep because they’re “busy” or “need to wake up early to work out.”

This is a big mistake. If you’re not sleeping well, if you’re not recovering well in general, you’re wasting most of your workouts. You can have the best, most dialed-in routine on earth, that you execute with flawless discipline, but if you’re not sleeping, it was all pointless.

“Because the modalities can be ranked by their order of effect, it pays to invest most heavily in the big factors, and just make sure you aren’t grossly violating the smaller ones. If you’re just starting to think about how to improve your recovery—and thereby your performance—your best bet is to get good sleep and plenty of food, along with reducing your volume and intensity of training when fatigue gets too high”

Alright, I’ve said the word "recovery” a bunch of times by now. What does it MEAN?

Rennaisance Periodization tells us Recovery is:

The return of physiological systems to baseline, which results in a restoration of athletic performance to predisruption levels, or at least to levels sufficient for further overload training.

Overload training, in RP parlance, is training that’s disruptive and challenging relative to your existing abilities.

And who is Renaissance Periodization?

Dr. Mike Israetel - Phd in Sports Physiology, trainer of Olympians, powerlifter, bodybuilder, and BJJ expert.

Dr. James Hoffman - Phd in Sports Physiology, Rugby and Strength coach, competed in Rugby, Football, and Wrestling.

Dr. Melissa Davis - Phd in Neurobiology and Behavior. BJJ world champion in IBJJF.

I’ve bought basically everything RP has ever published - if you want deep dives into any given aspect of training, diet, or recovery, they are the ones to go to first, because they know it academically, and more important, they know it from empirical results and coaching elite athletes at a high level, and can tell you both the theory and practice at every level of detail.

But back to overload training.

The whole game of becoming better, stronger, faster? Overload, getting tired, fatigue, is the linchpin. If you want to see gains from your training regime, fatigue is unavoidable.

If you’re still able to perform at the same level at the end of a training session as you could at the beginning, the chances that you will improve by your next session are minimal. Training is supposed to make you tired, and it’s normal to see your performance decline during a session. This idea, although intuitive, is not always appreciated.

They add one more nuance:

Cumulative fatigue requires more careful management, but its underlying processes are essential to gains. The reasons for this are summarized by two training principles: Overload and Stimulus Recovery Adaptation (SRA). The Overload Principle states that in order for training to make you better, it must be disruptive and challenging relative to your existing abilities. The SRA Principle states that once you’ve recovered to about 90% of full training capacity, you must resume training at a higher intensity in order to maximize accrued gains, which might otherwise be lost waiting for total system recovery. Together, these principles evidence that cumulative fatigue is necessary for adaptation to occur.

So to maximize accrued gains your training regimen needs to push and disrupt you, you need to recover until you’re about 90%, then push and disrupt again at a higher intensity. This is a great rule of thumb to have in the back of your mind.

And fatigue is caused by all sorts of things:

Your training

Daily tasks

Poor nutrition

Inadequate sleep

Stressors

Illness

Alcohol and other drugs

This goes back to my earlier point - you need a schema in your mind of how important various pieces of life, training, and recovery are. Fortunately, they’ve done that for us, too.

Behold, the pyramidal guide to performance excellence!

So let’s hit these, piece by piece:

Training within your MRV

They have a whole separate book on this (of course), called How Much Should I Train?

I’ll condense the best-of:

Training must be hard, and that the next training session must be harder than the last: overload and progressive overload.

On what time scales? Functional ones. If you’ve trained deadlift so hard you can’t bench two days later because your back is too sore and you can’t maintain the right back arch, you haven’t recovered, and you were outside your MRV. Or on a 3 month scale, your cumulative progression and fatigue has been great, so you cut your deload week in half, and on the next 3 month cycle, you can’t progress - you were training outside of your MRV.

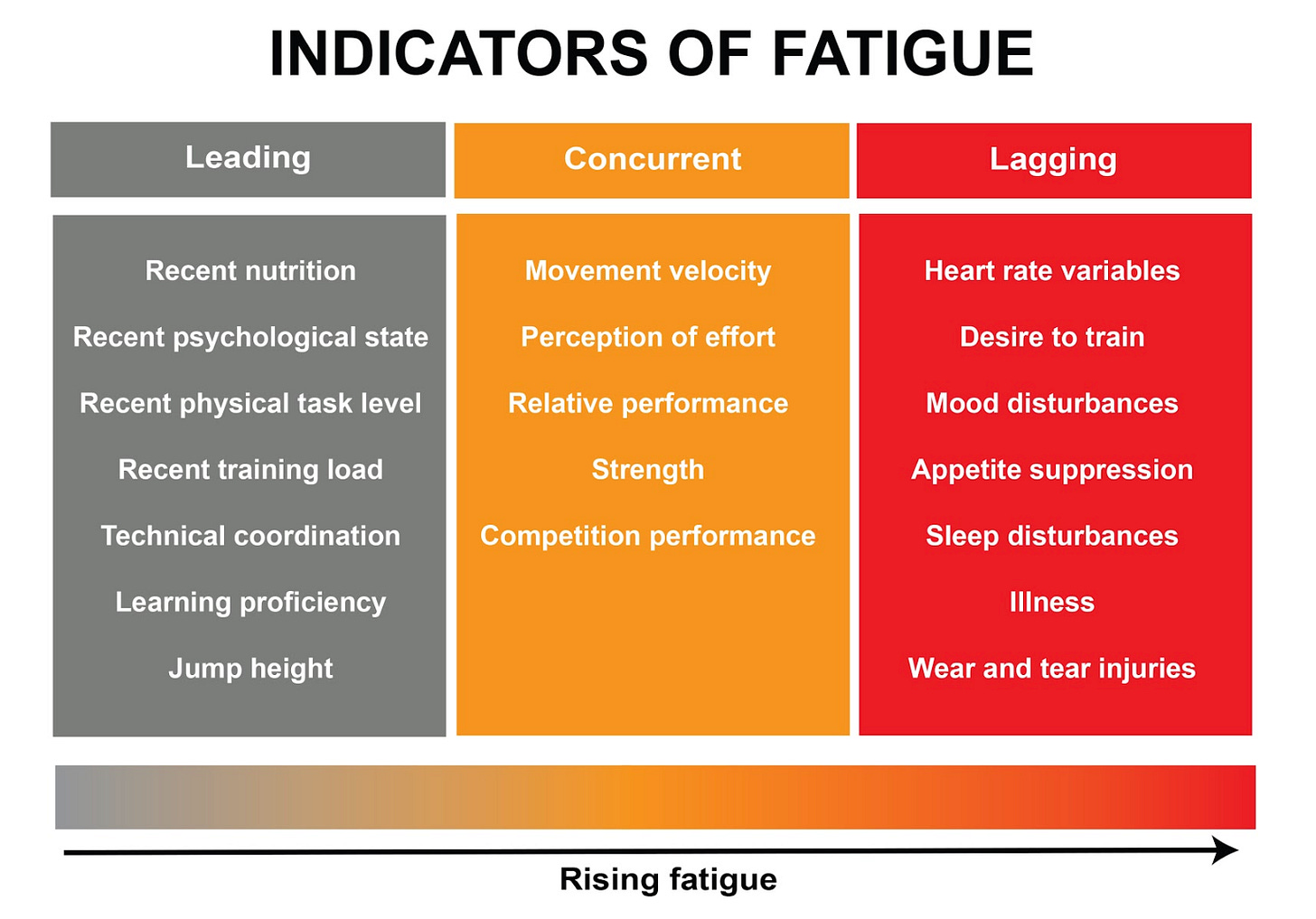

Wait, all those are retrospective? Yup, it kinda sucks. It’s something you find out later, but then you need to have observed along the way, so you can tie it back to leading and lagging indicators. Knowing your MRV in a given context is something you dial in over years of training, generally.

You use your MRV to design your training programs. Broadly, sessions should be routinely getting harder, while you recover between them to about 90%.

“Recovery is defined as ‘a return to the performance ability level existent prior to the current dose of training.’ So, if you usually run a 6:30 mile, and you’ve healed from squatting-induced soreness and are back to running 6:30 or faster, we can say that you are ‘recovered’ in the technical sense. Of course, if your thighs and glutes are still burning from those squats during your next run, and you only manage an 8 minute mile, you haven’t recovered, illustrating that sufficient amounts of training volume will inhibit one’s ability to do so.”

What are some of those leading and lagging indicators to look for?

You can definitely be past the leading and solidly into the concurrent markers and still be within your MRV, but then your MRV-meter at the mesocycle (3 month) level is probably about full, so I hope it’s close to your deload week.

So not to belabor the point, but THE MOST IMPORTANT THING for recovery, and therefore adaptation and performance, is training hard-but-not-too-hard. Within your MRV. It’s tempting to keep pushing, but down that road lies overtraining1 and injury.

Alright, let’s start looking at actual recovery stuff!

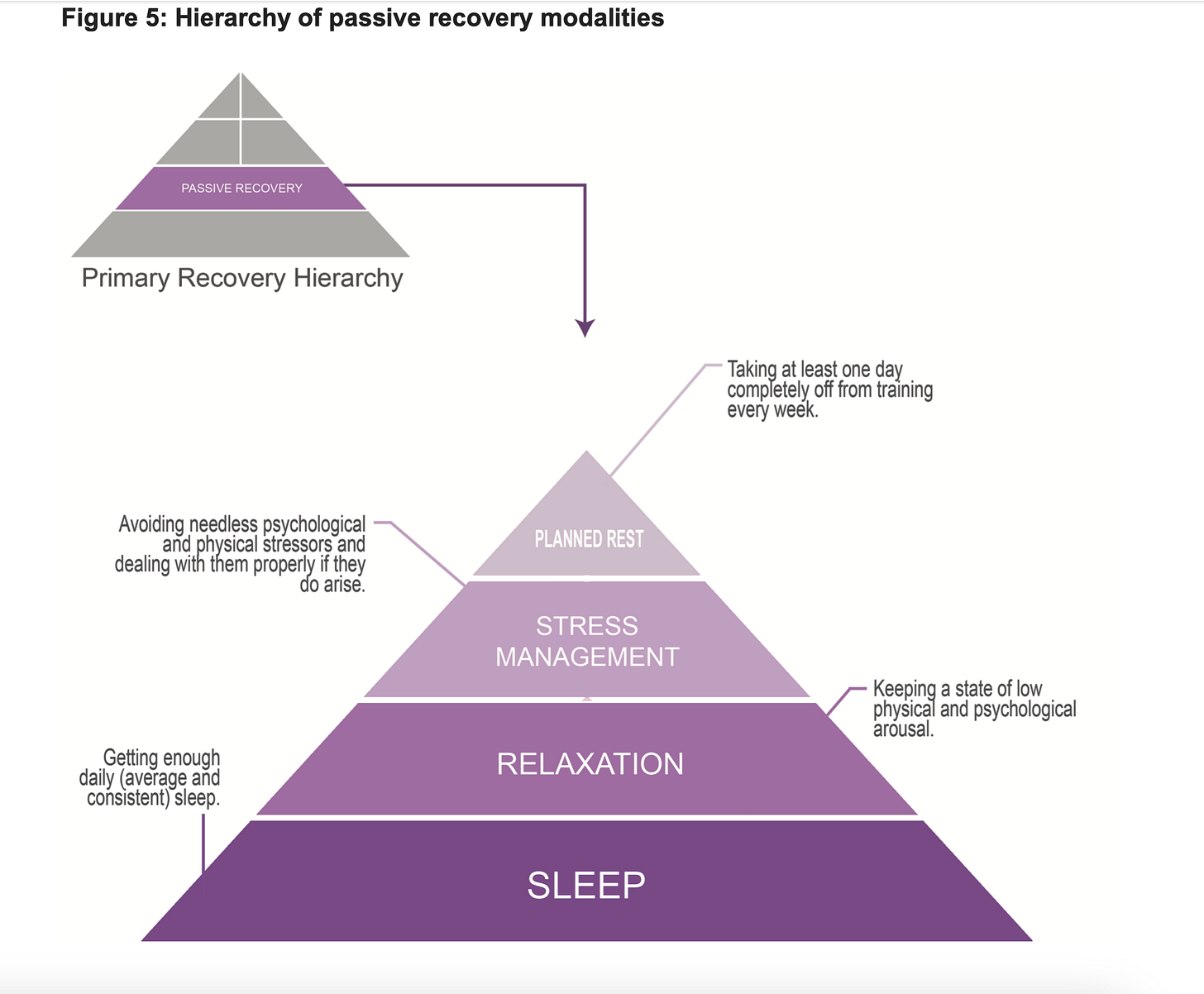

First up, Passive Recovery:

SLEEP - spend more time and bandwidth optimizing this. It’s the second most important thing after actually working out, but it’s the thing everyone wants to cut first!

Sleep hygiene:

Wear a sleep mask

Block blue light from devices

Stop using devices a few hours before bed

Stop eating several hours before bed

Melatonin 0.3mg

If you’re prone to stuffy noses or allergies or breathing problems, I have to advocate for the single biggest “sleep improver” I’ve experienced myself: Rhinomed Turbines - a little plastic dongle you put in your nose to breathe better overnight

Also, wash your pillowcases and sheets frequently, it really helps sleep quality

Naps:

20-40 min - if you nap longer you need to sleep more

Naps are usually easiest 7-8 hrs after waking

Try to time your naps regularly

Do low stress things before a nap

Don’t nap hungry - it’s a chance for your body to build and recover more

Don’t use alcohol or sedatives to nap

Jet lag

Exercise as soon as you can

No caffeine

Naps

Here’s the SSC jet lag melatonin dose and scheduling.2

The rest are pretty self explanatory - largely, be lazy, minimize stress in your life, and take at least one full rest day.

I’m not as good at the “be lazy,” or low physical and physiological arousal, part. I have a treadmill desk, and love it passionately, and it’s by far the most-utility-per-dollar thing that I’ve ever bought. But I still do fine, I think your body can adjust to a “slowly walking” baseline just as easily as a “laying around like a sack” baseline.

I’m just saying, I wouldn’t overindex on that one unless you’re literally a pro.

Nutrition

Love it, not much to say.

Tips on optimizing eating:

Yes, getting enough calories is very important for recovery. Especially if you are trying to move your weight either up or down, or attain increases in strength, power, or muscle mass, you need to be counting every calorie.

If you don’t know what macros are, it’s how many grams of fat, carbs, and protein are in your calories.

Carbs - if you’re training for about 1 hour, eat 1g of carbs per pound of body weight per day, for 2 hours eat 2g / lb, and so on. This replenishes glycogen and promotes uptake of nutrients into the muscles.

Protein - .75g per lb of body weight. If you’re 200 lbs, that’s 150g per day.

Fat - makes up the rest of your calories after hitting your carb and protein benchmarks, generally. Twice as calorie dense per gram - 9 cals per gram vs 4 cals in carbs and protein.

Timing - more carbs should be consumed immediately post training, to replenish glycogen and aid recovery.

I highly recommend meal prep if you don’t do it already, because it saves a bunch of time and helps you dial all these in.

If you’re like me and struggle to get *enough* calories, and want some high calorie advice and a few staple high calorie recipes, search meal prep in my triathlon training post here.

Supplements - creatine and maybe protein powder are the only ones worth anything.

A mesocycle is a roughly 1-3 month block of training in progressive overload. Some people need a deload week every 4 weeks, some every 12, and some in between - figure out what works best for you.

I definitely recommend light or deload sessions when ill or struggling with a bunch of exogenous life stuff - that way you don’t lose all your adaptation and progress, but don’t push so hard it makes everything worse. A deload or light session good rule of thumb is “roughly 50% in planned volume.”

Easy to neglect, but the most fun parts!

I personally swear by sauna and hot tubs. I’ve established many of my most long running and impactful friendships recovering in the sauna and chatting after a hard gym session, and I’ve owned hot tubs with great joy for many years.

I also swear by cold showers and cold exposure, things like jumping out of the sauna and rolling around in the snow or swimming in icy cold water. I got deeper into cold exposure in my Wim Hof review here.

Massage is pretty great, too! My only complaint is that it’s hard to find a masseuse strong enough to really get in there, but if you do, it’s amazing.

They also mention compression gear and electrical stimulation like TENS, which I have no comment on.

But keep in mind, these are the least important things for progress and recovery.

If you spread yourself evenly over all of the modalities, irrespective of their importance, you’ll get a good result, but not the best possible one. Likewise, if you were to prioritize a less important modality like hydration and took every step to optimize it but did so at the cost of tending less to other more important modalities, you’d net a very small percentage of your potential recovery. On the other hand, if you instead put that effort towards a more important modality, like sleep, by tracking and optimizing your sleep patterns, you’d net a huge fraction of the benefit of all of the modalities, because sleep is so critical to recovery.

Broadly, train big, eat big, sleep big, and spend all of your optimization energies on those three things until you’re VERY sure they’re dialed in well and running on autopilot.

How to tell if you’re overtrained?

Triangulate three to four signs to know:

Sleep: Poor sleep, low sleep quantity, tiredness, insomnia.

Soreness: if you’re slow and tired and achy consistently for a week or more.

Appetite: if you’re not as hungry as usual for several days, or if you’re losing weight.

Changes in HR or HRV:27 either up or down can mean something, and it’s not a strong indicator, but paired with other reads it can be an extra piece of evidence.

Frequent infections or illnesses.

Energy level - if your mood or energy level has been struggling for a week or more with no good reason.

If you want a deeper dive with a couple of actual diagnostic tests using blood pressure or pupils, search for “triangulate” in my post here.

Basically, either take .3mg of melatonin 9 hours after you woke up, or right before going to bed in your new time zone.

“Most studies say to take a dose of 0.3 mg just before (your new time zone’s) bedtime.

This doesn’t make a lot of sense to me. It seems like you should be able to model jet lag as a circadian rhythm disorder. That is, if you move to a time zone that’s five hours earlier, you’re in the exact same position as a teenager whose circadian rhythm is set five hours later than the rest of the world’s. This suggests you should use DSPD protocol of taking melatonin nine hours after waking / five hours before DLMO / seven hours before sleep.

My guess is for most people, their new time zone bedtime is a couple of hours before their old bedtime, so you’re getting most of the effect, plus the hypnotic effect. But I’m not sure. Maybe taking it earlier would work better. But given that the new light schedule is already working in your favor, I think most people find that taking it at bedtime is more than good enough for them.”

0.3mg not mcg, right?