I really enjoyed reading Alex Pentland’s1 Social Physics - it inspired a lot of ideas, a lot of skepticism, and a lot of digging deeper, which is a sign that it’s a pretty fruitful vein of thought and ideas.

It’s even more fun, because this was written in 2014, an idyllic pre-Woke / DEI and pre-COVID time, so we can look at his ideas through those lenses and try to predict how they would have done.

What is social physics?

“Social physics is a quantitative social science that describes reliable, mathematical connections between information and idea flow on the one hand and people’s behavior on the other.”

Many things about social interactions and dynamics follow statistical laws and are measurable. Zipf’s law, economic gravity, degrees of separation, triadic closure, homophily, the degree propinquity affects close relationships, and more.

But there’s been no underlying *theory* of social physics, just these empirically measured outcomes. What Pentland claims (but doesn’t deliver on) is the first groundings of that theory. And just to not keep you in suspense, his theory is it’s all network mediated.

“This book presents the beginnings of such a practical theory, and is based on a series of my papers that have recently appeared in the world’s leading scientific journals. This theory is a deceptively simple family of mathematical models that can be explained in plain English and gives a reasonably accurate account for the dozens of real-world examples described in this book.”

The math is pretty simple - it’s just matrix math and Hidden Markov Models. He has links to code and data in the books, but all the ones I checked are dead now. You can see some of his projects here. From what I understand, you can find a lot of the insights via standard graph theory and network analysis.

And I’ll give him credit, he’s not your usual “big theory” hedgehog, he wants it to be *useful.*

“The ultimate test of a practical theory, of course, is whether or not it can be used to shape outcomes. Is it good enough for engineering? To answer this question I will show how this new theory is already being used to create better companies, cities, and social institutions.”

I mean, on the one hand I’ve got to applaud him for wanting his theories to be useful and to drive economic value in the world, and for being willing to put them to this test.

So, in his favor, he’s actually used it to improve financial returns, drive marketing results, and cofounded at LEAST five companies from it.2

“Currently, a social physics framework is in daily use in several commercial deployments, serving tens of millions of people in tasks such as financial investing, health monitoring, marketing, improving company productivity, and boosting creative output.”

But on the other hand, I found a lot of his ideas to be pie-in-the-sky at best, and borderline dystopian at worst.

I think it’s important to remember the context here - in the times he was running the experiments and interventions (2011-2013), smartphones were basically brand new, and were the hot new thing. The vast amount of data they represented, available to be used in smart new ways, was dizzying, and there was a lot of low hanging fruit. Some if it was indeed financially valuable, and promised great potential for beneficial social or health interventions, and he was on the leading edge of that trend.

Indeed, he’s continued to be on the leading edge of a lot of trends - Alex “Sandy” Pentland is a furious dynamo of idea generation and company-founding in leading edge fields, with an impossibly high h-index of 156(!) and cofounder status / ownership in a passle of companies. Somebody it’s probably worth dedicating some attention to.

So let’s see what the rest of his book has in store for us.

“Social physics functions by analyzing patterns of human experience and idea exchange within the digital bread crumbs we all leave behind us as we move through the world—call records, credit card transactions, and GPS location fixes, among others.”

He mentions they can predict diabetes and credit worthiness as two offhand examples, but it must go much deeper. So many things are socially contagious, or at least strongly socially correlated - obesity, smoking, hobbies, SES, education levels, and more.

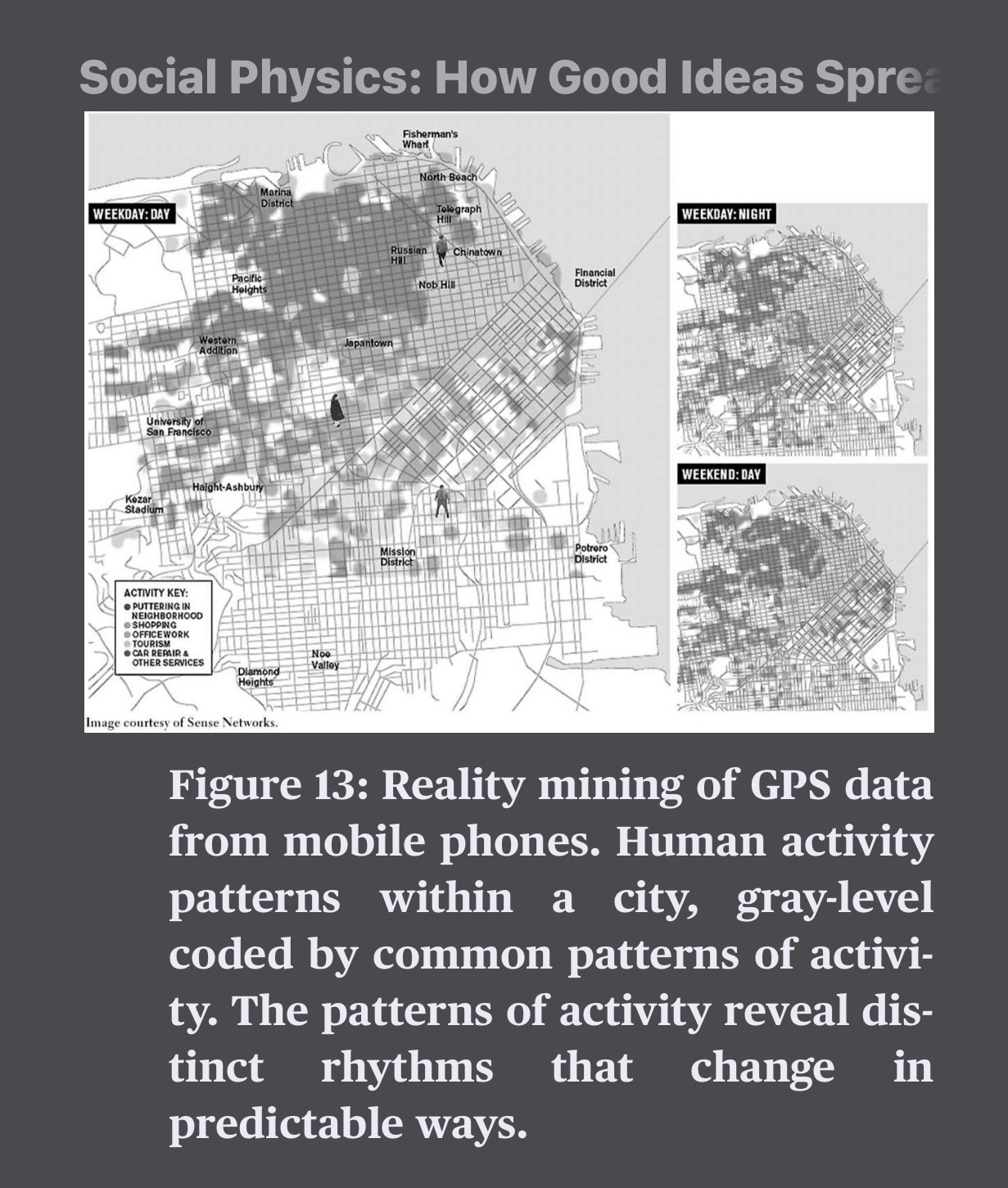

Pentland and a motley team of Phd students and post-docs measure entire “social organisms” this way - groups, companies, communities, “reality mining” for insights, which was a fun blast from the past.

Remember when “data mining” and “big data” were new, and big deals? Ah, that halcyon age.

He makes sure to call out that he’s made specific privacy protection tools and opt-outs when studying people and groups, and has even worked with companies to create a “New Deal on Data,” but we all know how worthless that is by now - if “social physics” is actually worth money, it’s going to be exploited by every unscrupulous company and troll farm on earth, as well as the mammoth-tier FAAMG data gobblers with nary a privacy tool or non-dark-patterned opt-out in sight, just like today. Not to mention the NSA and Five Eyes snaffling everything in sight and storing it in perpetuity, which will certainly be data-mined by advanced AI’s at some indeterminate point in the future.

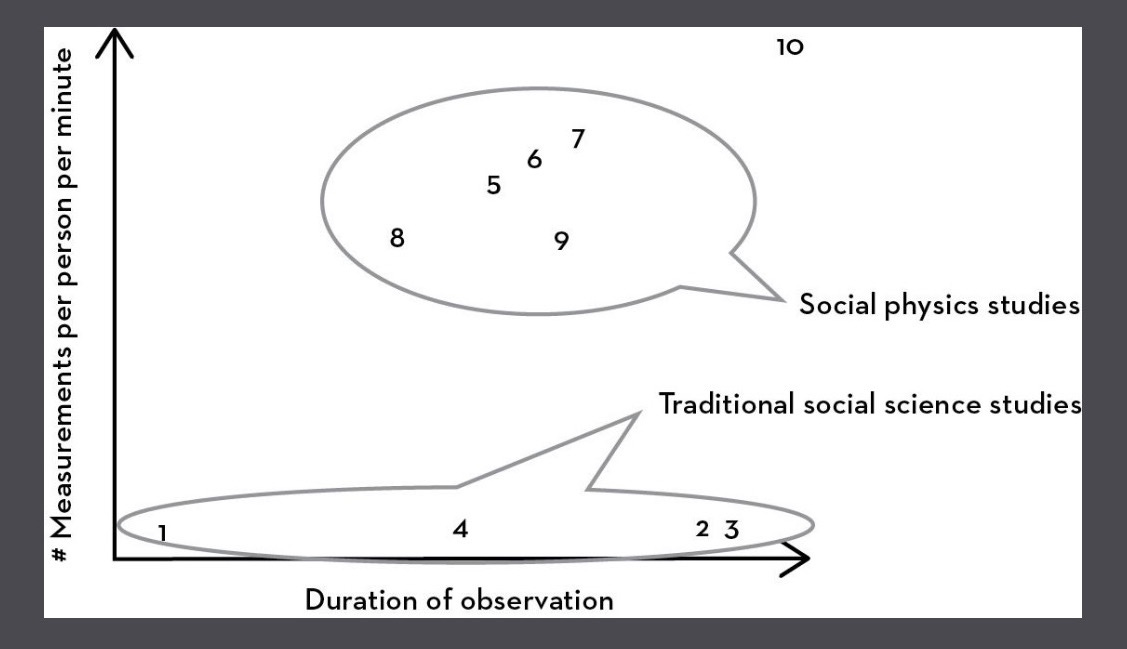

He points out that current social science data sources suck, surprising nobody. It’s all surveys and averages and single-snapshot-in-time peeks, but a true social physics relies upon and uses much more comprehensive and detailed data.

The funniest thing is he thinks (10) is where we were headed ten years ago.

I mean obviously, 10 already exists, everyone has had smart phones for a decade+ now. 10 is the NSA and China and Google. But the funny part is he thinks these data sets will be opened “more widely for scientific inquiry”.

“Importantly, the point labeled 10 is where the world is headed. In just a few short years we are likely to have incredibly rich data available about the behavior of virtually all of humanity—on a continuous basis. The data mostly already exist in cell phone networks, credit card databases, and elsewhere, but currently only technical gurus have access to it. As they become more widely available for scientific inquiry, however, the new science of social physics will gain further momentum.”

But on the other hand, obviously not? Especially if social physics is actually useful enough to drive financial outcomes and marketing, which is his headline result and conceit? Google or Facebook or Alibaba isn’t just gonna hand you or anyone their data, they’ve built a trillion dollar company on that data, and every other company wants that data because it’s valuable.

And China and the NSA sure as shit isn’t opening up their data to anyone, much less “scientists.” And they’re definitely not agreeing to any sort of privacy-respecting “New Deal on Data” either.

Sure, they’re gonna recruit as many “social physicists” as they can from MIT and Caltech and wherever, but I promise the data is staying closed and in-house. So not sure why he hasn’t seen those obvious dynamics, especially given it’s the sort of thing he measures. And it’s not like he didn’t know - he’s credited with being a cofounder and helping create the marketing and analytics arm of Alibaba in 2013, the same time many of the starred flagship book studies were published.

The two most important concepts for social physics are:

Idea flow - finding new strategies and behavior and coordination

Social learning - how new ideas get adopted or become habits, and how learning is accelerated or shaped by social behavior

In other words, “social physics seeks to understand how the flow of ideas turns into behaviors and action.”

Ok great. So we all know social science sucks,3 what have you got for us, Pentland?

He’s going to talk to us about Social Physics for people, companies and managers, and cities.

Fundamentally, making a decision as an individual or a group is about exploring the ideas available, then evaluating and making a decision.

It’s an ancient problem, one we’ve had to solve since well before we were human. Animals and even insects have to decide where to forage as a group, where to place their nests or colonies, and much else.

Bees scout for locations, waggle dance, and form quorums that decide. Elephants, ravens, and chimpanzees vocalize once they start moving to coordinate on where the group moves to. Dolphins vocalize and coordinate their swimming as a group to herd and hunt schools of fish. The list goes on, seemingly forever.

Humans do the same, although our vocalizations usually contain a little more information. Interestingly, he points out that in humans, we still have the same wiring underneath as our forebears, and that entirely ignoring words, you can segment what role somebody is playing - and who is subordinate to who - in a conversation via pauses, ums, ahs, tone of voice, speaking length, interruption, and a few other cues.4

But we still make better decisions as a group. It’s essentially our superpower, both in the past, and now - our market economy and much scientific progress is built on it.

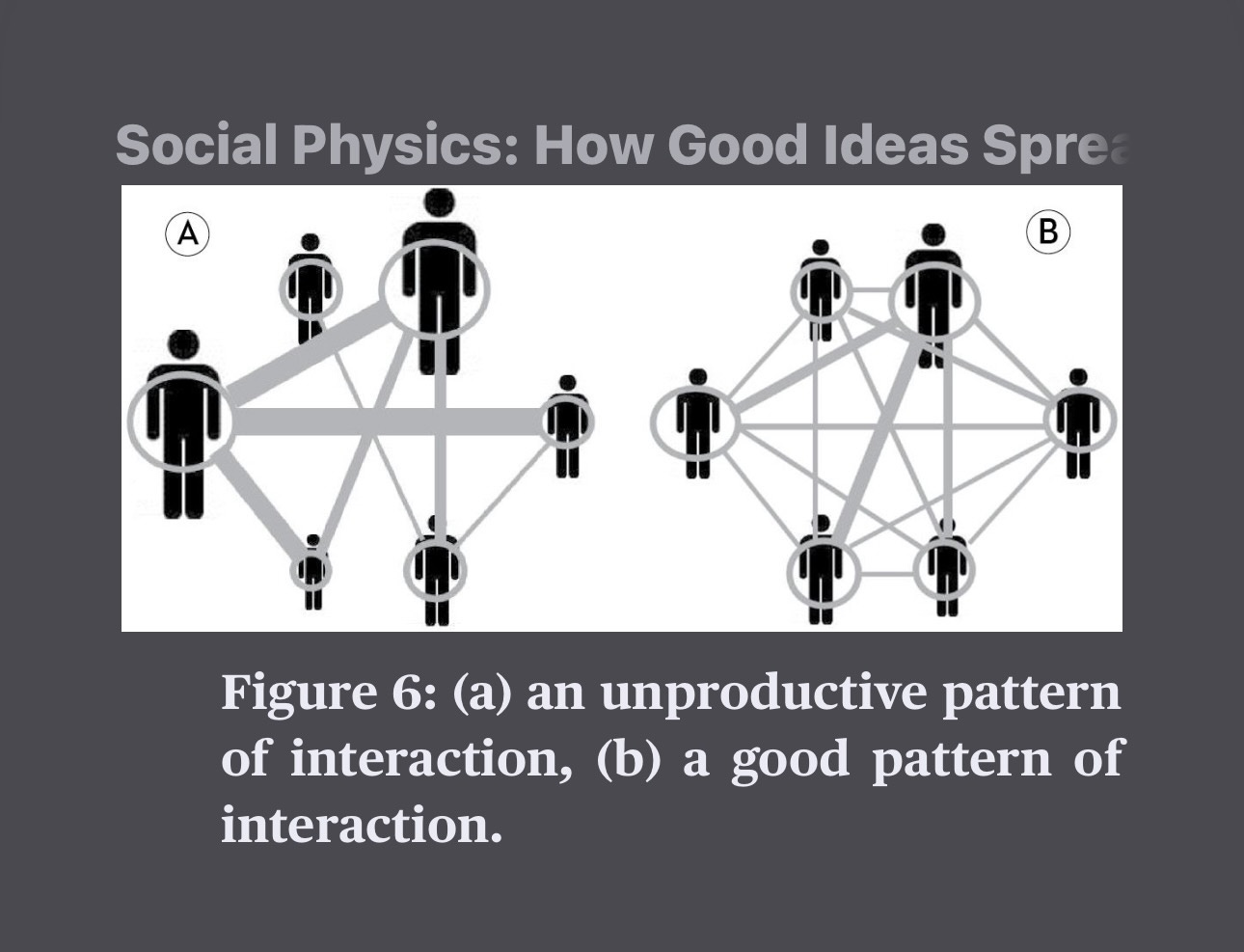

The social network and connections within that group, as well as the group behavior and behavior of the individual comprising the group, are a big predictor for the quality of those decisions.

Both in studies on group decision making and in “more than two dozen” businesses, he cites that as much as 50% of the variance in performance stems from the patterns of idea flow in the group! That’s huge! Assuming it’s an r-squared of .5, that means r is ~.7, absolutely massive for social science.

“In studies of more than two dozen organizations I have found that interaction patterns within them typically account for almost half of all the performance variation between high- and low-performing groups. This makes the pattern of idea flow the single biggest performance factor that can be shaped by leadership, and yet today there isn’t a single organization in the world that keeps track of both face-to-face and electronic interaction patterns. And, as we all know, what isn’t measured can’t be managed.”

And yes, he’s founded a company to do this, and it’s being used in the real world today, ten years later. They even created a device and later a phone app that helps serve as a real-time dashboard for a group in a meeting.

And what matters for good idea flow in a group? Rough equality in conversational turn-taking.

At a macro level, you need everybody to contribute ideas in the “explore” phase, where ideas are surfaced and explored and refined. Groups where one or a few people dominate do strictly worse.

He cites a fairly crappy academic paper to back this, which looks at many groups of 2-5 undergrads who are asked to do brainstorming, judgment, and planning tasks, and then are evaluated on “group IQ,” and which finds that cohesion, motivation, and satisfaction matter not at all to group performance, but instead (the paper crows), after conversational dominance, it is the number of *women* in a group that is the biggest determinant of performance and “group IQ.”5

It’s actually how well the group members do at the Reading the Mind in the Eyes test, or EQ / social intelligence / theory of mind, on which doing better is correlated with being a woman.6

But since he’s literally built a successful business around it, I assume the principle more or less generalizes, or at least that he has more insights and secret sauce he’s not sharing in a public book.

Once you get people contributing roughly equally in the explore phase:

“Wen and I found that three simple patterns accounted for approximately 50 percent of the variation in performance across groups and tasks. The characteristics typical of the highest-performing groups included: 1) a large number of ideas: many very short contributions rather than a few long ones; 2) dense interactions: a continuous, overlapping cycling between making contributions and very short (less than one second) responsive comments (such as “good,” “that’s right,” “what?” etc.) that serve to validate or invalidate the ideas and build consensus; and 3) diversity of ideas: everyone within a group contributing ideas and reactions, with similar levels of turn taking among the participants.”

He claims that his business can get mixed language, fully remote, and hybrid remote teams to the levels of trust and performance of in-person teams with his company’s tools and practices. Valuable if true, especially post-COVID.

What’s the difference between average and star performers?

Here he looks at Bell Labs. This was a really interesting section in my own opinion.

Many selective companies know that you can hire two people based on similarly stellar external metrics - Ivy degrees, publications, past work accomplishments, github repos - but that no matter how high your “quality” filters, the actual performance of those individuals can widely diverge. Some will be average performers, and some will be star performers.

What differentiates the stars?

“The most consistently creative and insightful people are explorers. They spend an enormous amount of time seeking out new people and different ideas, without necessarily trying very hard to find the “best” people or “best” ideas. Instead, they seek out people with different views and different ideas.”

Stars develop dependable two-way relationships with a wide array of people and experts in different parts of the business. Being able to think with multiple points of view, and being able to enlist help in other areas of the business lets you tackle a wider array of more impactful problems.

They adopt an energetic and engaging interaction style,7 which is better for both idea flow and establishing relationships.

“Along with this continuous search for new ideas, these explorers do another interesting thing: They winnow down their most recently discovered ideas to the best ones through their habit of bouncing them off of everyone they meet—and remember that they meet many different sorts of people. Diversity of viewpoint and experience is an important success factor when harvesting innovative ideas. The ideas that provoke reactions of surprise or interest from a wide range of people are the keepers. These are the ideas that are harvested, assembled into a new story about the world, and used to guide actions and decisions.”

Sounds pretty actionable from our own individual perspectives,8 and aligns with things I’ve seen in my own life. If you connect a lot of diverse worlds and networks, it fosters innovation and can be good for you and all the networks you are a part of - in fact you could say you have a duty to the networks you care most about to connect widely and bring back the best from other worlds and networks they’re currently unaware of.

Especially as a leader, I endorse the following:

“Thinking about your job as improving idea flow, getting everyone to talk to each other, and connecting between groups, can be very effective in improving performance.”

But what about as hiring managers?

Is there some way to discern these super-connectors before hiring them?

Pentland is silent on the matter - I wouldn’t be surprised if he has a recruiting and hiring company built around this floating around somewhere, which I’d be happy to give a try. I searched for one, but didn’t find it.

What I’ve always personally done when hiring is favored people with a diversity of interests, especially counter-trend interests. Generally when you’re hiring talent at this level, it’s all people from the same “coastal elite” monoculture, and it’s actually *hard* to find “diversity” at this level - diversity in the intellectual and background sense, rather than the racist / DEI sense.

But if a candidate is connected to a non-coastal-elite social circle, I take it as a promising sign. They race cars, or have a private pilot’s license, or do woodworking, glassblowing, blacksmithing, or something physical. They took a weird career path. They spent 5 years in a non-Western country. It’s not a sure thing by any means, but it’s a strong enough net-positive bet I’ll usually take it.

Idea flow.

Let’s talk about idea flow. Popular conceptions tend to think of memetic contagion and spread as being like the flu, including the potential to go viral.9 Ideas basically never go viral in practice, however - although they do depend on spread and susceptibility. You’re more susceptible to an idea in your social network if you trust or admire the person demonstrating it, if they’re enough like you for it to seem relevant, and if it fits in with the rest of your life.

Idea flow is an important measure of how well a given social network works at collecting and refining decision strategies.

People’s decisions are a blend of personal and social information. When people see others adopting strategies similar to their own, they often become more confident, and invest more in that particular strategy.

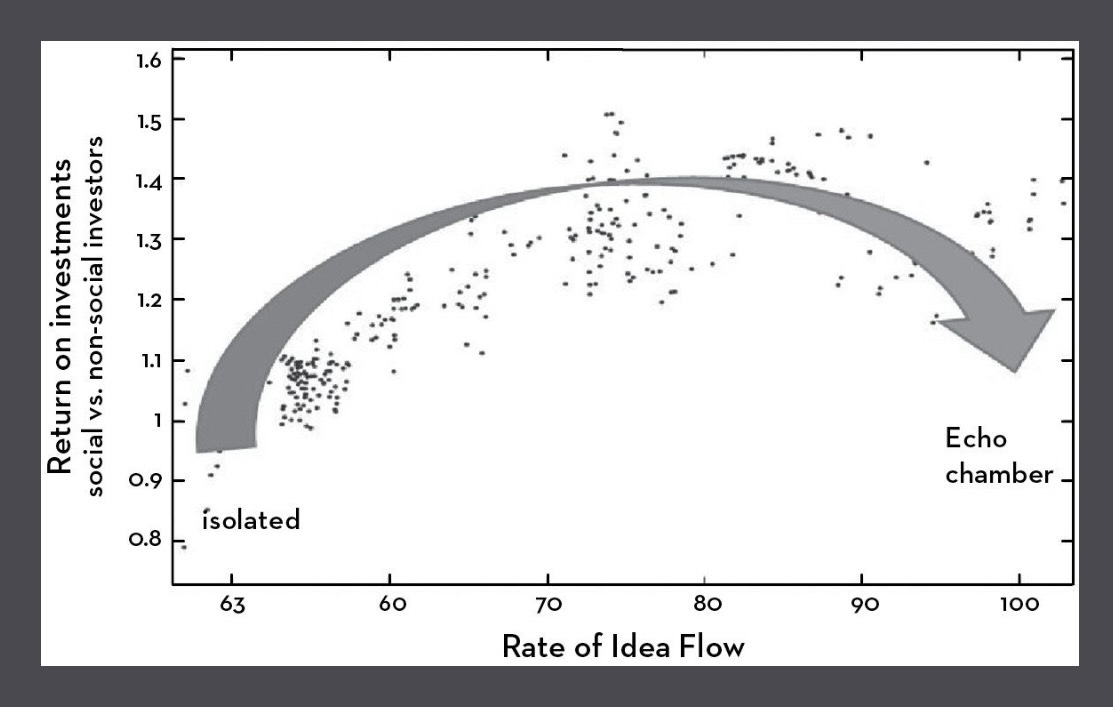

When this goes wrong, it leads to overconfidence, group think, and feedback loops.

“Similarly, when there are feedback loops in the social network, then the same ideas circle around and come back again and again. But because ideas usually change slightly as they go from person to person, they may not be recognized as repetitions of the same ideas. It is easy to believe that everyone has independently arrived at similar strategies, and again become more confident than is warranted.”

Him and one of his researchers were able to look at the eToro social / financial network, and tune the social network so that it remained in the healthy “wisdom of the crowds” region.

“As a result of this tuning we were able to increase the profitability of all the social traders by more than 6 percent, thus doubling their profitability.”

They created a company to do this for more places, and ten years later it’s still going and has active job postings, so a pretty healthy recommendation from my POV.

What is Pentland’s advice to avoid echo chambers? He gives three methods:

Bayesian truth serum - find people who can reliably predict how others will act, but act differently themselves. These people have independent information.

Discount common knowledge - first ask what everyone thinks everyone else is going to say. Then discount this as common knowledge.

Pentland’s own - look at the network graph and discount info coming from clusters of similar people, to elicit independent info.

Three “idea flow” takeaways:

People use a combination of individual learning and social learning to make decisions

Diversity matters - if everyone seems to be going the same direction, they’re probably in a feedback loop, and it’s smart to bet against it / go the other direction

Contrarians matter. When people are going against the crowd, they likely have valuable individual information. If there are enough of these people to impute or aggregate a consensus direction from a decent chunk of them, this is “a really, really good trading strategy”

“One disturbing implication of these findings is that our hyperconnected world may be moving toward a state in which there is too much idea flow. In a world of echo chambers, fads and panics are the norm, and it is much harder to make good decisions.”

lol - from 2014, folks!

Peer pressure - it’s what’s for dinner!

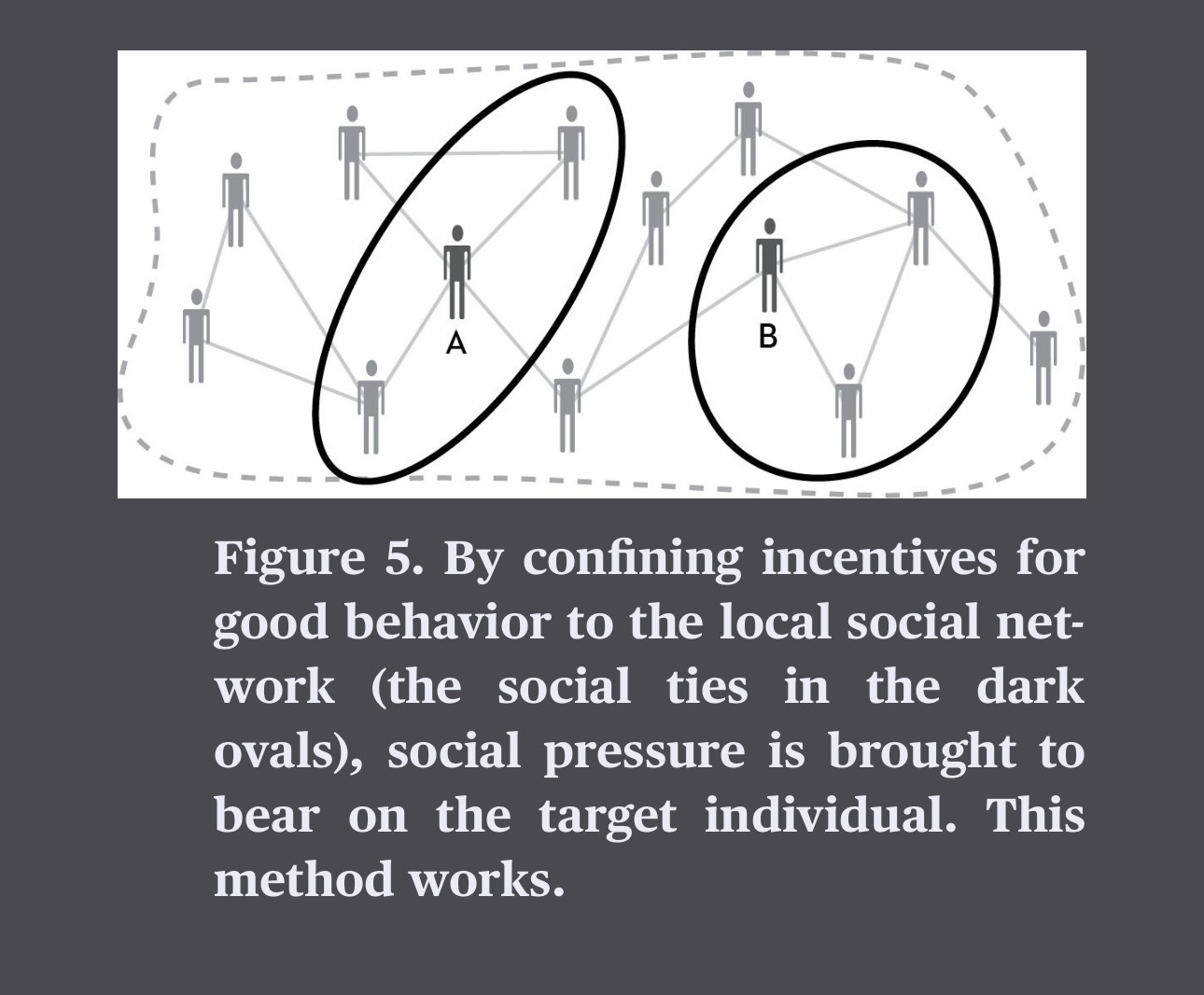

Another interesting lesson from Pentland’s work is the power of peer pressure.

He looked at weight gain. As we all know, it’s a one-way ratchet.

“What we found was that weight change showed a very strong association with exposure to peers who gained weight but not to those who lost weight.”

It’s no surprise that your close friends or family influence you - one of the more interesting findings was that “ambient” peers matter a lot too, in fact what your “ambient” peers are doing is more important than what your friends are doing!

“In fact, exposure to the behavior examples that surrounded each individual dominated everything else we examined in this study. It was more important than personal factors, such as weight gain by friends, gender, age, or stress/happiness, and even more than all these other factors combined. Put another way, the effect of exposure to the surrounding set of behavior examples was about as powerful as the effect of IQ on standardized test scores.”

They measured political effects, and they were as strong as obesity effects, and mediated the same way (ambient peers).

But, this argues that interventions using peers should be a high potential, largely unused tool.

We’re all familiar with those studies that show that you can shame high electricity using consumers into using less by showing them the smaller amounts of power their neighbors use. What if we could operationalize that on a larger scale?

Pentland claims his group is able to “work out mathematically how best to motivate people by using social network incentives to increase their cooperation. These incentives alter idea flow by creating social pressure, increasing the amount of interaction around specific, targeted ideas, and thus increasing the likelihood that people will incorporate those ideas into their behavior.”

What do they tackle? Exercise! One of my favorite topics.

Surprising nobody, laziness, much like obesity, is sticky. In cold winter months in Boston, people get less active, and that tends to stick. It’s a ratchet effect that only goes “down,” just like weight only goes up.

“And so Nadav Ahrony and I deployed FunFit, a system of social network incentives within the ongoing Friends and Family study that encouraged people to remain active. Everyone in the Friends and Family study was assigned two buddies.”

Some buddies were close, some acquaintances. Everyone both had buddies and was a buddy. They then gave small payments to a person’s buddies if the person in the center of the cluster exercised more, to use peer pressure and social dynamics.

How did they do? He claims it worked 4x more efficiently than traditional incentives, and in the strongest “buddies,” 8x as well.

And he claims, it stuck. People who received social network incentives maintained their higher levels of activity even after the incentives disappeared (I was skeptical of this, but couldn’t verify, because in the actual paper there’s only a few paragraphs and no actual data in the supplemental info).

Wow, sounds pretty great, right? But how did they do in an *absolute* sense? I had to dig into the actual study to see. It was pretty ugly.

“The average normalized activity levels (measured by accelerometers) of the three groups were as follows: (a) 1.162 for the control group, (b) 1.266 for the peer-see group and (c) 1.216 for the peer-reward group”

So they started out with a stdev of about 0.5, and with both intervention groups at least 1 stdev higher, before any intervention.

Their interventions ended up here:

The change in the average normalized activity levels (measured by accelerometers) of the three groups were as follows: (a) 0.037 (3.2%) for the control group, (b) 0.070(5.5%) for the peer-see group and (c) 0.126(10.4%) for the peer-reward group.

So once you take the control increase out, it was basically noise for the peer-see group, and the peer-reward group MIGHT have moved the needle between 3-6% in the positive direction.

He never gives absolute accelerometer or activity numbers or minutes, even in the Supplementary Materials.

We know from Dan Lieberman’s Exercised that the vast majority of exercise interventions do nothing, and the strongest top out at around 5 minutes more of exercise per day, or ~25-30 min more per week. That’s about a 25% increase for a sedentary modern.

So Pentland’s exercise intervention of 3-6% was probably 1/5 as the strongest (pretty terrible) exercise interventions we know about. Womp womp.

Where it might do okay, though, is in cost-for-effect.

He cites a “four times the behavioral change per dollar of incentive.” The actual numbers he cites were $83 for individual incentives, $39.5 for peer-see, and a mere $12 for peer reward, which had the largest effect size.

We’d need to do a rigorous cost benefit analysis versus the other 5x more effective exercise interventions, but directionally it seems like there might be some juice there? Still, if you bet *against* any given exercise intervention, you’ll pretty much always win.

In a classic “shame the electricity users” test, shaming with peers got reductions of around 17%, which is pretty good compared to the usual 2-8% “shaming with letters” averages. Which argues that directly-incentivized peer effects might be twice as strong there, or just that the in-person channels are that much stronger than direct mail.

But at the macro level, if it points at a more general trend, the idea that peer pressure might be 7x more effective than individual incentives in some situations is pretty big if true. For your kids, changing their peers will do way more than begging them or paying for performance.

For yourself, choosing more athletic, successful, or intellectual close friends and peers will naturally persuade you to push yourself and achieve more on those dimensions.

Cities - the final frontier.

"I view great cities as pestilential to the morals, the health, and the liberties of man.”

“They are the sinks of voluntary misery, and the abode of depredation, corruption, and wretchedness."

—Thomas Jefferson

Alright, so when you deploy these algorithms and tools on people in cities, what do you get? And can you improve things? This is the section where I had the most laugh-out-loud moments and skepticism.

People’s phones show everything about them - traffic flows, where they live and work and play, which places are staples and which they’re exploring anew, who they spend time around, where they spend nights outside of home, and much else. This all seems really obvious to me, and this whole section seemed like it was written for the notable scientific journal “Duh,” but I guess it still surprises some people?

Surely, with all this data, we could get smarter about how we run our cities?

Certainly, we can use this data to build behavioral profiles and segmentations.

“people within the same behavior demographic have similar food habits, similar clothes, similar financial habits, and similar attitudes toward authority, and as a consequence, they have similar health outcomes and similar career trajectories.”

“In my experience, these behavior demographics typically provide predictions of consumer preferences, financial risks, and political views that are more than four times as accurate as standard geographic demographics based on zip codes. They also accurately predict people’s risks for diseases of behavior, such as diabetes or alcoholism.”

“Specifically, continuous streams of data about human behavior allow us to accurately forecast changes in traffic, electric power use, and even street crime and the spread of the flu.”

Much like his naivete about “A New Deal on Data” and privacy, he seemed really disconnected from reality here to me.

And what are his use cases for this awesome data and segmentation ability?

Traffic analysis and optimization and forecasting

Electricity analysis, etc

Street crime

Spread of flu and epidemiology

Amber alerts

Badgering people who are bad with money or likely to get diabetes with public health campaigns

Remapping public transportation to link more groups and promote more exploration in a city

Finding critical supplies after a natural disaster

Political campaigns

Recruiting new employees

He envisions a Traffic AI optimizing traffic flow, and some other pretty simple use cases. Waze is already on the road there, obviously we’ll all eventually have self driving cars and won’t care about traffic.

“Remapping public transportation to link more groups and promote more exploration in a city” seems like a particularly bad use case, because he explicitly calls out wanting to link poor and “isolated neighborhoods with worse social outcomes” and thinks this will somehow increase productivity, entirely ignoring the fact that all of his other use cases have been heavily selecting for high human capital people with pro-social behaviors and motivations (undergrads in studies, large businesses, etc).

It seems an obvious recipe for increased crime and further reductions in public transport usage, but what do I know? Especially given he says he’s shown “that idea flow along social ties accurately reproduces urban features, such as the rates of HIV / AIDS infections, telephone communication patterns, crime and patenting rates, and more.”

In terms of epidemiology, they found that people’s regular behavior changes in predictable ways when they become ill, so he’s positing measuring that to identify cases of illness (then notifying those people and / or the government). Disturbingly, he finds that the pre-symptomatic changes are that people start interacting with “more but different people,” and given it’s pre-symptomatic, that’s probably not doctor visits. Given how we handled COVID, I think it’s safe to say there was essentially zero people doing this type of analysis and intervention well, or that it fails on unspecified implementation details.

He DID predict Cambridge Analytica, though - people indeed use this data for political campaigns.

The richer the city or person, the more exploration.

Two interesting things he brought up - we all know cities are idea factories, and the bigger, the better. Things like patents and businesses founded scales more than linearly with size, as you can read about in Geoffrey West’s Scale.

Not surprisingly, “exploration destinations,” or interesting places beyond home and work, also occur at higher rates in larger cities. Because of the “greater than linear” effect, they become overrepresented in cities that are growing more wealthy - not only does exploration result in more creative and richer cities, but the process is self-reinforcing.

I’ve always thought of it as fat tails - the more people there are in a city, the more a given business can succeed even if it only appeals to 10%, or 1%, or 0.1% of the people in the city, and the more such businesses there will be.

And rich people explore a lot more - you can actually segment somebody’s wealth by how often they “explore” and step outside of their usual destinations. It’s directional - families that lose wealth explore less.

Two last lol moments.

He has this whole section where he rants about markets and Marxian classes and how his deal is somehow the solution. “Adam Smith’s markets end up being as dehumanizing as Karl Marx’s classes.”

He seems to think because people are members of many different peer groups according to hobby, neighborhood, church, workplace etc, this is somehow better and less dispositive and rigid than markets and social classes, but he’s literally showing us the bijection between these things in the book! If you can *predict* wealth, peers, neighbors, career, and church with this data with high accuracy, that is the direct mapping from “market” to “class” to “Pentland smartphone demographics.” Why would the smartphone segmentations change anything??

Second one - he and some of his team analyzed US gov data about which companies buy from which suppliers, and found constrained, asymetric relationships. This is good because it leads to stable, trusted relationships. This is bad, because it leads to fragility and lack of resilience if one supplier disappears or has problems, as we saw in the GM bailout and during the COVID-induced supply chain shortages.

What’s really funny is that he’s actively working with finance companies and open sourcing some of these tools and algorithms, but thinks that Goldman or some hedge fund wouldn’t intentionally buy and shutter some highly connected supplier to wreak havoc on a market or set of companies they’re shorting. Which seems a pretty obvious play, even if it is net destructive to GDP overall - heck this is pretty close to what some private equity firms do TODAY.

Three design criteria for better social design:

I’ll close with his three design criteria, which I found similarly laugh-out-loud.

Social efficiency - optimal distribution of resources in society. Pentland wants to create a more explicitly exchange-based society instead of “always having to resort to open market mechanisms.” I actually don’t understand what he’s saying - he’s yammering a lot about privacy and data commons, and presumably suggesting something on the lines of “making more individual data publicly available, but with privacy protections” but I have no idea why he thinks this would do anything on this front. It basically sounds like he wants to create alternate trust-groups - like in ye olden times, where if you were a religious or ethnic minority, you would trust your confreres more than “default society” people. But if it’s about trust, people will hide or selectively share times they’ve screwed other people, and you’re not going to trust them without a history of reciprocal interaction anyways. If it’s about “distribution of resources” EVERYONE will hate it, because it’s about narcing everything you do in real time to the feds (as though that's not already happening via PRISM and other things). So I actually didn’t understand what he’s getting at here at all, despite rereading it three times.

Operational efficiency - infrastructure should work quickly, reliably, and without waste. Our current “financial, transportation, health, energy, and political systems all seem to be failing us.” And this is back in 2014! Ha! He proposes a public data commons that “lets us all see the big picture in real time”. Examples include sharing anonymized medical records to discover which drug treatments work best and discover dangerous drug interactions. Another is getting people to adopt changes, because people tend to ignore or misuse systems of transportation, health, etc. Basically, he wants to use social physics to develop and enforce useful social norms. I think this is absolute pie-in-the sky, because all of his examples in which this worked are explicitly subsets of high human capital people in environments where they are explicitly likely to be prosocial and civic minded. This just doesn’t work when you try to extend it to everyone in a city. The median person is not conscientious, high human capital, pro-social, or civic minded, and probably never will be, no matter how much you try to “influence” their peers.

Resilience - the long term stability of our social systems. Avoid systemwide failures and crashes, respond quickly and accurately to changing threats and disasters, etc. Given how we handled COVID, our overall declining state and civilizational capacity, and inability to build anything so simple as housing in any city people actually want to live, much less putting a man on the moon, I think we’re safe to say there has been either zero or negative movement on this in the intervening 10 years since the book. So, good luck with that. He also hasn’t shown or hinted at anything actually interesting, like being able to look at aggregate large-scale network effects or dynamics that only happen with 100, or 1k, or 1M people with his models.

But what are the takeaways for us?

I still think there were some valuable takeaways from the book, and that being able to create several companies that have lasted more than ten years is a pretty good sign he’s pointing at real effects with actual value.

Think about your job as improving idea flow, facilitating everyone talking, and connecting between groups.

Become a “charismatic connector.” Connect widely, engage in many interesting and high energy conversations, harvest ideas broadly, and bounce ideas off multiple types of people from all areas.

Contrarians matter. When people are going against the crowd, they likely have valuable individual information.

In a meeting or group setting making a decision, make sure everyone gets their say, and prioritize a good back and forth. You want a large number of ideas coming from a cycle of short contributions and responses.

Curate your close friends and “ambient peers” carefully - you’ll become more like them, so make sure they represent what you’d be happy to become.

What would you get from reading the book yourself?

More cuts on idea flow dynamics, with lots of great infographics and many more case studies

The story of how he won the DARPA “Red Balloon Challenge,” finding ten red balloons DARPA hid across the US in under 9 hours, beating out 4,000 other teams

A ton of cites to papers that point in various interesting directions

A bunch of dead links to old projects, code bases, and data sets

Finally, he talks a big game about having the underlying *theory* to unify all the empirical social phenomena we’ve noticed like Zipf’s law, homophily, social gravity, and more - but he doesn’t really do any unifying, and that unification doesn’t seem to have happened at all in the ten intervening years.

The thing that I would most like, but also doesn’t exist - in the ten years since the book was published, there could have been a rigorous exploration of the limits of peer pressure and influence using studies informed by his mathematical models and theoretical base. Where it affects people, how much, in what contexts, how you can use it to shape yourself or your kids - Pentland points at potentially interesting directions, but if it exists or has been explicated in the ten years since, I haven’t been able to find it anywhere.

Overall, the book definitely promised more than it delivered, and didn’t have much *really* unique insight you couldn’t have found in other books - but I feel that if he can cofound 5 companies, many of which are still operating a decade later, there has to be something to it, and there’s a core of value and insight in there.

h-index of 156(!!). According to his MIT bio page:

“He is one of the most-cited computational scientists in the world, and Forbes declared him one of the "7 most powerful data scientists in the world" along with Google founders and the Chief Technical Officer of the United States. He co-led the World Economic Forum discussion in Davos that led to the EU privacy regulation GDPR, and was one of the UN Secretary General's "Data Revolutionaries" helping to forge the transparency and accountability mechanisms in the UN's Sustainable Development Goals. He has received numerous awards and distinctions such as MIT's Toshiba endowed chair, election to the U.S. Academy of Engineering, the McKinsey Award from Harvard Business Review, the 40th Anniversary of the Internet from DARPA, and the Brandeis Award for work in privacy. Recent invited keynotes include annual meetings of OECD, G20, World Bank, and JP Morgan.”

Cogito Corp, Athena Wisdom, Sense Networks, Sociometric Solutions, and Ginger.io by my count in the book, his MIT bio page has a few more, but I think they came after

“The scientific method as currently practiced in the social sciences is failing us and threatens to collapse in an era of big data. Is coffee good for us or bad? How about sugar? With billions of people consuming these products for over a century, we ought to have the answers. Instead, we have “scientific” opinion that seems to change every day. We need to revive the social sciences by constructing living labs to test and prove ideas for building data-driven societies.”

“In several studies of small groups solving problems, we instrumented each person to measure both their social signaling and their pattern of interaction. We found that each of the different social roles that psychologists identify, i.e., protagonist, supporter, attacker, or neutral, uses different social signaling and, as a consequence, different patterns of speaking length, interruption of others, frequency of speaking, etc.”

“Early human groups needed to pool ideas in order to solve shared problems, much as ape groups are observed pooling ideas today. Animal behavior research supports the idea that this is what ape troops, and even bee colonies, do when deciding about group actions. Our sociometric badge data demonstrate that this is also what happens in modern group problem-solving “sessions. The back-channel “ums” and “OKs” that greet new ideas in today’s conference rooms preserve and leverage these ancient mechanisms for sorting through alternative ideas.”

“The same is true of the information content: Someone contributing a new idea speaks differently than someone who is orienting the group to return to a previous idea or someone who is neutral. As a result, each person’s pattern of interaction can be used to identify their functional role—follower, orienteer, giver, seeker, and so on—without listening to the words.”

“Similarly, just as social signals determine the dominance network in ape colonies, the patterns of conversations in modern humans determine people’s places in their social networks. In particular, the social structure can be figured out from the pattern of who controls conversation, that is, who initiates conversation, who interrupts, etc.”

Although he explicitly avoids mentioning it, if you dig into the study, the max IQ of the smartest member was actually more important (r=.29) than “social IQ” (r=.26), but both were beat out handily by groups where one or a few people dominated (r=-0.41). Again, these were groups of 2-5 undergrads.

Cohen’s D of 0.2-0.3

“The charismatic connectors are not just extroverts or life of the party types. Rather, they are genuinely interested in everyone and everything. I think their real interest is in idea flow, although probably few would describe their interest that way. They tend to drive conversations, asking about what is happening in people’s lives, how their projects are doing, how they are addressing problems, etc. The consequence is that they develop a good sense of everything that is going on and become a source of social intelligence.”

“People can teach themselves to be charismatic connectors—they are made, not born. The trick is to do what creative people do: they pay attention to any new idea that comes along, and when something is interesting, they bounce it off other people and see what their thoughts are; they also try to expand their social networks to include many different types of people, so they get as many different types of ideas as possible. They use the coffee pot or water cooler to talk to the janitor, the sales guy, and the head of another department. They ask what’s new, what is bugging them, and what they are doing about it, and trade their ideas for ones they’ve picked up from other people. ”

Interestingly, I read Derek Thompson’s Hit Makers book on virality, and it basically never happens - when ideas spread to millions or billions of people, it’s always as a result of spreading to one - or many - large “one to many” conveyors of information. Think Oprah, or the Daily Show, or the news, or one of the big YouTube stars. Ideas never get “big” just person to person, in other words, it takes big broadcasters of ideas who reach a lot of people at a time.