Tips from a master maker / doer

Mythbuster Adam Savage's book, Every Tool is a Hammer

Do you know what I’ve noticed as the biggest distinction and common thread among the people I most like and admire?

Making

The people I like make. They create, they DO, they bring new things into the world, they fix, they make things better.

The great majority of people consume and waste and destroy, and that’s pretty much it.

The average person buys junk and fast and other processed food for nearly all their meals when they’re already fat, they use a ton of energy as their default for basically no reason1, they buy a lot of stuff and throw away a lot of stuff, they never fix anything, and they never make or create anything.

When it comes to “entropy” they’re definitely on a side, and although it’s technically the winning side,2 it’s not the side that gives us anything we collectively want.

This actually highlights one of the things I like most about makers and creators - it doesn’t take very many of them to make things better for everybody. We can get by with something like Pareto splits - if only 20% of people make and create, we’re individually and societally generally okay.

What is a maker?

Makers create new things. In thoughts and words, sure, but largely with things that actually tangibly impact the world or other people. They invent a new product. They found a new company. They fix cars and buildings and the infrastructure of our cities and houses. They weld a new oil pipeline, or build a new power plant. They write code that does new and useful things. They create the shows and apps that the great bulk of average people mindlessly consume for 7-12 hours a day.

Adam Savage is a maker extraordinaire, and reading his book was a fun romp through his projects and personal journey as a maker.

Hard won lessons

It’s another example of the genre: “incredibly hard-won lessons that took many years of being beaten mercilessly and repeatedly with real-world consequences, eventually resulting in a set of practices and mental and physical habits that looks like ‘wisdom,’ that he will now try to distill into words.”

These are always fun, because it never works, more or less. Sure, it’s a finger pointing at the moon, and that rare reader or acolyte will attain enlightenment once every thousand times you point at it - but for the other 999? Definitely “have to spend years for the world to beat those lessons into you, too” territory. I’m one of the 999, by the way, which is why it’s delightful and funny to see the same lessons with the same etiology from somebody else you respect.

And hey! 1/1k is actually pretty good conversion if you have an audience as big as Adam Savage! He’s hopefully meaningfully improving the lives of many thousands of people with this book, who will attain some better practices along the path to “maker enlightenment,” and avoid some of those harsh lessons!

The P -> J conversion

Okay, we all know Myers-Briggs isn’t as good as OCEAN / Big 5 in terms of predicting life outcomes.3

But as a useful way to think about people’s personalities, I think there’s one area it excels - J vs P. This is “judging” versus “perceiving.” It’s kind of a combination of “conscientiousness” and “time preference,” but it boils down to “do you think about the future regularly and take steps to make it better?” A “J” is proactive, versus a “P” is largely reactive.

Many makers start out as “P’s” by inclination when they first come into the world and start making, because of correlations with creativity and intensity. But “making” as a discipline rewards “J” thinking, and punishes “P” thinking and practices pretty heavily, so many Makers go through a process of having the value of yucky and aversive “J” behaviors essentially beaten into them over the years, until finally they embrace them and become advocates.

Adam Savage went through exactly this journey, starting as a passionately creative young man in NYC whose workshop was cluttered with trash and “found objects,” and ending with him-today exhorting readers on the value of lists, thinking ahead, and cleaning and organizing your shop and tools every day.

Anyone whose gone through a similar journey (myself for one), will recognize that and chuckle.

“Today, I am a fairly well-organized maker, but I used to be quite well known for the opposite. I was a messy guy. I mean like a REALLY messy guy. Those piles of trash on the floor of my first studio in Brooklyn, the ones that I sifted through to make art, that was nothing. Or rather, that was the tip of the iceberg. That lack of organizing structure carried through to my personal life, as well. I was a messy person, I was a messy roommate. I was awful to live with. I was a mess.”

What are the top recommendations from a top-in-the-field maker?

So what are those hard-won lessons, at a high level?

First, making is an extremely iterative process, a journey of hundreds or thousands of “failures” for every “success,” with lots of mistakes and back-and-forth. You need to be comfortable with ambiguity, not getting stuff right, and trying again and again as you refine your process and your skills and execute towards excellence.

“I have a prediction: you are going to mess up a lot. I mean A LOT. Whether from impatience or arrogance, inexperience or insecurity, lack of knowledge or lack of interest, you are going to tear seams, break bits, snap joints, misdrill, overcut, under-measure, miss deadlines, injure yourself, and generally just make a mess of things. There will be moments when, if you are not losing interest in a project, you are losing your mind about it. It will be confusing, dispiriting, and infuriating.

About this prediction, I have three words for you: WELCOME TO MAKING!”

“Making is messy. It’s full of fits and starts, wrong turns, and good ideas gone bad. New methods, new skills, new creations, they are all a product of experimentation; and what is an experiment but a process that may or may not yield expected results? WHO KNOWS?”

But aside from that?

Lists, lists everywhere!

Lists allow you to both keep track of each important detail, as well as your progress overall. Adam advocates a square checkbox that you fill in halfway-to-full to track progress over each list item. Don’t just make one master list, make a sub-list for each component or self-contained sub-assembly. This can get to the point of needing a list of your lists, but do that too!

Start with the worst and hardest thing, don’t save it for last. “Now it’s time to get working. I almost never begin at the beginning. Usually I examine the subcategorized list and I look for the toughest nut to crack. The real asskicker of a problem. The one for which I have the most difficulty imagining a solution at first glance.”

Mise en place

This is the concept in cooking where you chop and prepare and set out all your ingredients before assembling your main dishes. Similarly, he advocates doing pre-work to ensure you have all the tools, components, fasteners, and so on you’ll need before tackling something. This also allows you to look for optimization, because making is often about doing a lot of repetitive and incremental work.

“What is the scope of my work space? What materials am I working with and how much of them do I have? What tools do I need? Do I have them all? Are they in a good place? Are they in the best place? Could I put the glue cup closer? Will that save me time? Is there a custom holder that I could assemble that would allow me to paint these things faster? Maybe a multilevel drying rack will save me a few trips to the paint booth. Balanced efficiency is one of my coping mechanisms for tedium. I’m on a constant hunt for refinements in my assembly process.”

“But it’s about more than just clamping and cooling fluid, or even saving time. It’s about looking forward, into the near and far future, and making an assessment of what you truly value, so you are not reckless with it, or so impatient that you don’t do what’s necessary to see it through to fruition.

I know that sounds like hyperbole, but it’s not. Trust me, you’ve never tried to make a fourteen-foot floating balloon out of twenty-eight pounds of rolled lead.”

Prototype exhaustively, until you fully understand your project (drawing and cardboard)

Drawing several views of your project and / or prototyping in cardboard are basically superpowers, because they force you to ground your understanding and actually think about every aspect of the thing in a systematic way.

Cleaning and knolling

Back to the classic P→J conversion, Adam went from characteristically messy and working in cluttered workspaces to evangelizing cleaning up and ararnging things at the end of every workday. The advantage of this is that you set future-you up for success - when you get into your workshop, excited and engaged with a new idea, you can just start. You don’t have to spend 20 minutes cleaning up, or finding a tool or part in all the clutter. Preserving that momentum gets you more quality project time while you’re at your height of freshness, motivation, and ability.

Knolling is a combination of mise en place and cleaning up your area regularly:

“Here’s how to do it, according to Tom (and, really, common sense):

1. Examine your work space for all items not in use—tools, materials, books, coffee cups, it doesn’t matter what it is.

2. Remove those unused items from your space. When in doubt, leave it on the table.

3. Group all like items—pens with pencils, washers with O-rings, nuts with bolts, etc.

4. Align (parallel) or square (90-degree angle) all objects within each group to each other and then to the surface upon which they sit.

For a large part of my career, I worked in a consistent fashion: on an eighteen- by eighteen-inch square, in the middle of an overcrowded bench, surrounded by piles of stuff. My hoarding tendencies and my general impatience made any other kind of work environment a virtual impossibility. Knolling was an epiphany on the same level as adding checkboxes”

Your workshop corresponds to your personality, so set it up accordingly

A shop is uniquely an environment that you typically create and have a lot of leeway in terms of how things are arranged, where they are, what your workflows are, and so on. You should take the opportunity to optimize this for your personality and desired ways of working. He has a direct comparison to his former boss’ and costar’s workshop and style - Jamie Hyneman organizes everything by process type or material (so all hammers are in the woodworking area versus the fiberglass area), whereas Adam prefers buying 5 different duplicative hammers and leaving them in all the areas they’re useful, as just one example. Another interesting example of his is hating drawers - he wants to SEE as much as he can, so he’s fabbed little ladder-like things on wheels that hold a lot of tools visibly and in the open.4

“A shop is not simply a place to make things. Yes, it’s where we collect our materials, our tools, our notes, and our half-completed ideas, but it’s also a manifestation of how we think about organization, project management, and working priorities. Packed with our personal histories, the shop is where we get to enjoy the illusion that the universe has some order and that we as creators can pretend we have some measure of control over things. A shop is a meta-level tool for telling our stories. It is an autobiography of our whole experience as makers. It’s where the problems we choose to solve have stakes big enough to challenge us. It’s where our successes and failures play out in microcosm. It’s where we encounter the world, and confront our own minds.”

“Every shop, in this sense, is an individual philosophical discourse about how to work, one held up by personal beliefs that, like anything, evolve with time and experience and wisdom, but are always a reflection of you. They are reflected in the answers to questions we can always be asking ourselves as makers: What kind of work do I do? How do I like to work? What tools and materials do I use most often? Do I like it calm or crazy? Do I like shelves or bins or pegboards or drawers or racks or all of the above?”

Management and delegation

One of his important lessons, and one that snaffles most “new bosses,” is that giving negative feedback is absolutely necessary and valuable - for both the boss and the employee. That is how we get better! People shy away from it because they hate confrontation and don’t want to upset their employees, but that’s a major mistake, long term. Giving feedback, both positive and negative, is absolutely vital to helping people improve in their skills and delivery and capabilities over time. If you think back to your own journey, it was precisely by making mistakes, recognizing them, and then doing better that you increased in any skill, and you can speed that process up with both positive and negative feedback.

“What am I doing wrong? Why won’t this person ever learn?! It was a regular refrain in my inner dialogue between takes. Then one day I realized that all the most valuable stuff I ever learned as a maker came in the form of critical feedback from employers or clients—and I was providing almost none of that to my team. I’m naturally allergic to telling people things they don’t want to hear, but by looking at my own past, I saw how necessary it is to give proper, contextual feedback to the people you work with—to acknowledge their work, to appreciate their effort, and to correct their mistakes.”

Three stages of interacting with your direct reports and peers - thank, encourage, motivate. Thanking is pretty self explanatory - make sure that you acknowledge and are grateful for people’s work and time and efforts on your behalf. Encouragement comes from noticing and calling out great work, ideally publicly. And motivation is selling the vision and “giving someone the context for why they in particular are perfect for the role they’re performing; explaining how they contribute invaluably to the whole picture; and reminding them that you couldn’t do it without them.” Praising publicly, and performance-managing privately should also in here.

Assorted fun insights

“Assembly is an engineer’s way of saying “put things together.” This process of joining things together is always fraught with hard-to-see hazards, particularly since it usually happens last, and many of the most precarious and exacting operations within the physical making of things happen really close to the very end of a build. This makes the cost of failure high.”

“A skilled craftsperson has amassed enough knowledge about their particular discipline to move at a speed that is cost-effective: they don’t spend so much time on a job that they can’t make any money doing it. But for those of us who are generalists or ambitious amateurs making things for ourselves, we can often substitute that knowledge with time. This is the great secret sauce for tackling the unfamiliar.”

“Even if I had all the necessary skills and experience to execute a job perfectly, going it alone without any help would have been foolish. Not only is it less efficient, but how do you expect to learn new things or get better if you do everything in isolation? This was my biggest mistake, my truest and deepest failing: my aversion to asking for help. For more years than I would like to admit, “help” was a dirty word. I was great at giving it, and I never judged anyone who needed it, but I was terrible at asking for it, because it felt like failure—a very specific kind of failure that was unique to me.”

“My personal rule was that if I needed a tool more than three times within a year, it was worth investing in a good one of my own.

Still, I always started with a cheap version, partly out of frugality, but also because I found that it helped me shop for the good one.”

“Little known fact: baking soda is also an excellent accelerator for [cyanoacrylate, aka Super glue] glues. It kicks them almost instantaneously, and it doesn’t really smell at all. Sprinkling a little bit on glue you’ve laid down also makes it immensely stronger. I’ve used baking soda and CA glues to create gusset-like welds on the inside of styrene boxes that made them incredibly strong. I have known plenty of model makers over the years who can’t abide the smell of solvent kicker and only use baking soda.”

“I am continually looking for ways to adjust the layout of the shop to be more efficient, that is, to increase visibility and accessibility. Probably 20 percent of what I do on a daily basis, in fact, is making small changes to how things are organized—piece by piece, bit by bit, shelf by shelf, drawer by reluctant drawer.”

He recommends building a scale model of your house. (He does 1/24 scale for the house and surrounding property, and 1/12 scale for rooms). He calls out that this turned out to be surprisingly helpful a number of times - during renovations and going back and forth with architects and contractors, he was able to move an HVAC system into a better spot on the second floor by finding unused space behind a closet, it was easier to plan landscaping and deck building, it’s easy to rearrange a room’s furniture in the model (which he also builds, out of cardboard) and see how you both like it, and so on.

Why you should love deadlines

He also has insights on deadlines, the dreaded nemesis of many creative types. Because after all, wouldn’t it be nice to just be free from all deadlines and obligations? Free to follow your creative flights of fancy, and really commit and take whatever time it takes to really do it right?

No!

And speaking as somebody who retired in the last couple of years, I can tell you this firsthand, too. Deadlines are great, because if you have no pressure and no ship date, you get a LOT less done.5 Yes, life is easy and relaxed, but your objective productivity plummets, and your work quality isn’t really noticeably higher, you might do things to a 10-20% better standard, if that. The productivity / work quality tradeoff is NOT worth it.

Adam worked at ILM6 doing a lot of sets and props for various movies, and he relates a fun story where they’re tight against a 4 week deadline, and points out that if they’d had 8 weeks, it wouldn’t have been any more relaxed. This is because work and work quality generally expands to fill the time - if you’re 2 weeks out from shipping and you have a great idea for a fun flourish or a cooler way to do something, you’ll do it! And then you’ll be right back against the “last 3 days” crunch just like you would have been if you’d have the 4 week deadline.

But true to my own example, that fun flourish or cooler effect isn’t going to be vastly better - it might make the end result a couple of percent better, 10% better at the most!

Quality and productivity tradeoffs are absolutely real, and deadlines are your best friend if you actually want to get things done.

They clarify, they help you prioritize, and most of all, they help you actually deliver more finished projects. A deadline is your best friend, even though it often seems like your worst enemy.

“We don’t do well with time. We struggle to manage it, to take advantage of it, even to conceptualize it. When we have to get something important done, we often feel like we either have absolutely no time or all the time in the world. Either end of the spectrum can hamstring us. We feel crippled by too much or too little leeway, and then, nothing gets done.

We have several different names for this phenomenon, depending on how it manifests: procrastination, perfectionism, analysis paralysis, Hick’s Law, the paradox of choice. Whatever you want to call it, this tendency is the bane of the maker’s existence. More specifically, it is the bane of my existence as a maker if I don’t do something to mitigate it.

That something is almost always to make deadlines. Everything in the previous chapter was about ways to be more efficient and effective, how to ask for help and offer it to others. Deadlines are about helping yourself. I LOVE DEADLINES! They are the chain saw that prunes decision trees.”

Tools and toolmaking as amplifier

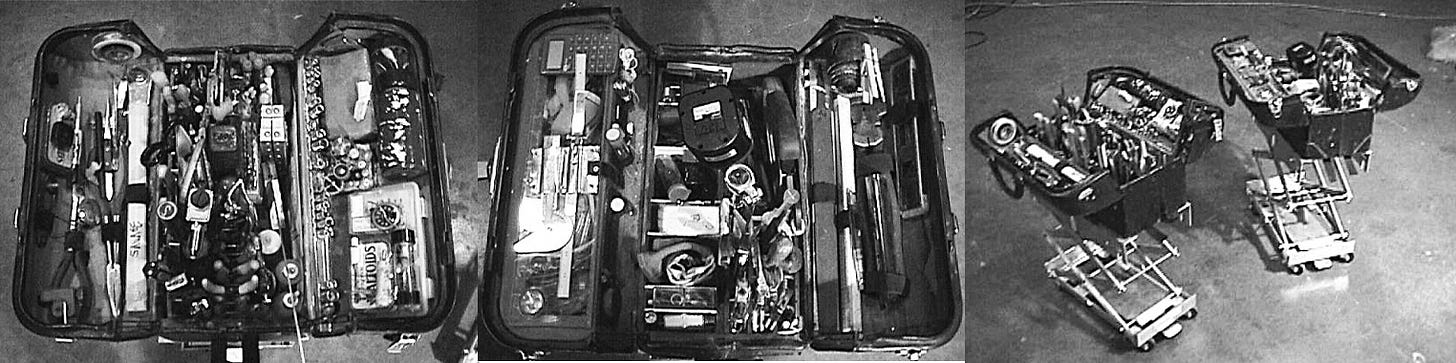

He has this whole vignette on him making his own toolboxes and iteratively improving them. First he finds he likes placing tools vertically, because it allows you to take more and organize them better, then he starts using antique doctors’ bags as toolboxes, then he puts raising legs so he can raise them to a useful height, then when they start failing due to too much tool-weight, he builds them from scratch.

The evolution:

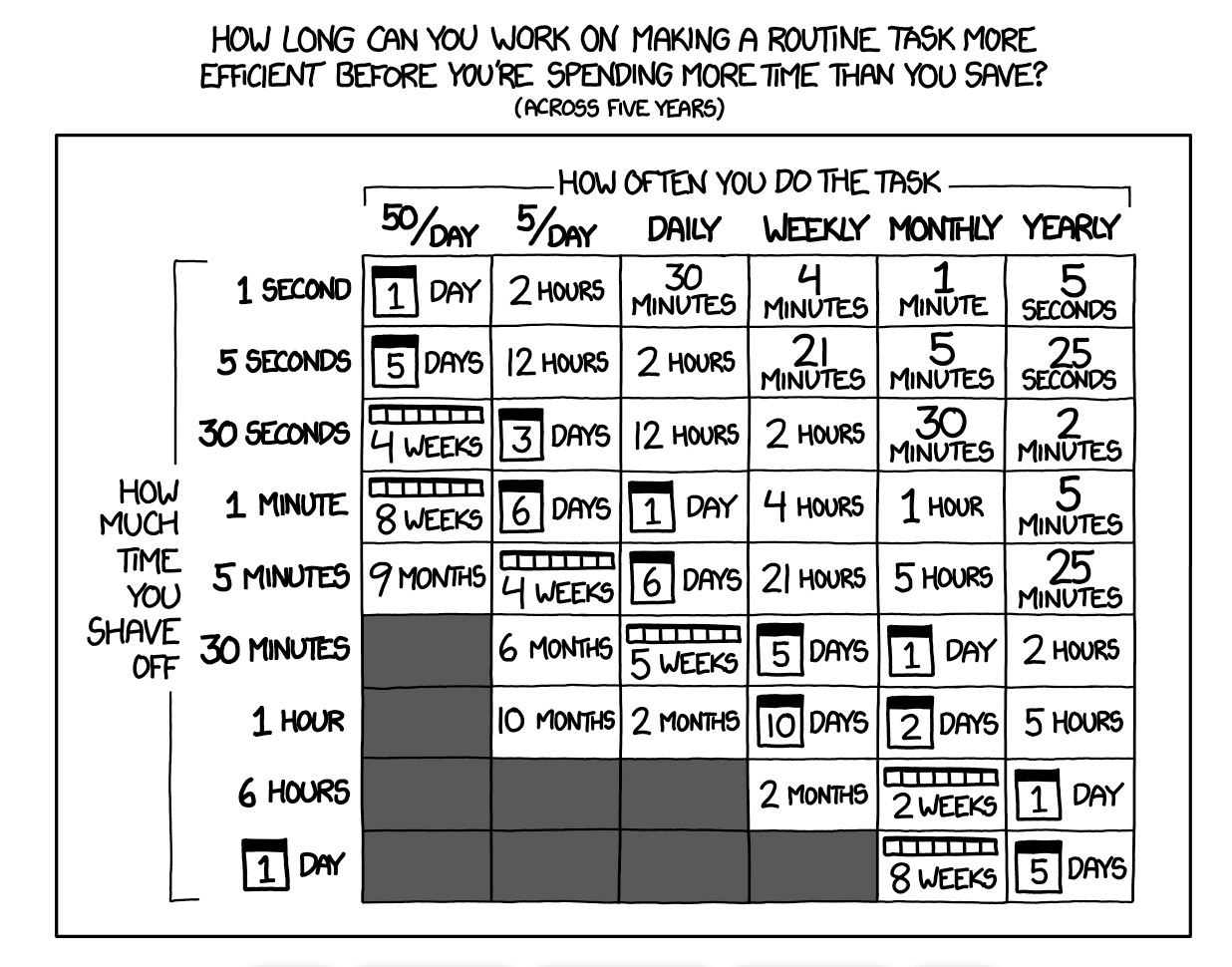

Just think of how much incremental productivity he enabled over the decades by ensuring he had the right tools, arranged the way he liked, at just the right height! It definitely met Randall Munroe’s productivity tradeoff:

And as awesome as those are, I think the overall lesson here is that as a maker, you’re not constrained to stuff you can find or buy. An entire optimization world is open to you that just plain doesn’t exist for the vast majority of people! And it’s not just about toolboxes, this is everywhere.

A handful of examples from my own life:

I’ve put together multiple little scripts that allow me to do things with just a few keystrokes: save a text file with a default name taken from the first words of the file, move files to certain directories, save video files from the web locally, and so on.

Me and my dad built a heavy-duty mild steel bumper for my RV incorporating a towing hitch and much sturdier supports and mounting hardware, so that it can tow roughly 3x the rated weight a regular towing hitch would allow.

I’ve built and use a private ACX “comment enhancer” extension that allows me to track and collapse read comments on ACX (useful for those 1k+ Open Threads), so only unread comments are visible and non-collapsed.

I built an “actually good” treadmill desk using an 800 pound commercial-grade Freemotion treadmill with 18% grade and a suspension, building an adjustable desk around it so it becomes the ultimate treadmill desk. It’s roughly 100x better than any of the cheap Chinese treadmill desks you can buy ready made (I should know, I’ve tried 4-5 of them).

I’ve built a little infrastructure around the “whisper” library so that any audio playing on my computer can be captioned in real time by an LLM, using my OpenAI API key.

I’ve built my own furniture several times, including a tropical theme bamboo-and-pine “emperor” size bed with lots of storage (the size of a queen plus twin-long mattress put together), various end tables built to fit specific nooks, an optimized workstation desk that fit my desktop and laptops and several screens gracefully, and more.

I had an awkward size and shape bathroom that needed more ventilation, so I built a custom high powered enclosure and fan to specifically fit the tiny space, with two 300+ cfm fans that could move a crazy amount of air and rheostat style power knob so you could dial in how much air you wanted moving.

One fun example from Adam’s life - he uses a Leatherman so often he always has one on his belt, and the holsters you can buy all have snaps. A true nerd (like most of us), he calculated unsnapping and resnapping the snap every time he used the tool was wasting too much time, so he built an all-aluminum Leatherman holster to such precision that it audibly snaps in and out, but is still easy and smooth to take in or out, and secure enough that it won’t fall out even if he’s upside down.

The point is that if you’re a maker, you’re no longer limited by what other people offer for sale - you can create exactly what you want, including better tools and ways of working that amplify further creation!

And this has a chance of becoming even more important and valuable in the near future.

Why should YOU start making and building more?

In addition to being on the right side of history AND thermodynamics, there are further benefits to making.

You know how we’re all relatively worried about a post-intelligence world counterfeiting all knowledge work, and counterfeiting all the mathematical and scientific and number crunching and programming skills we’ve built up over the years?

I say this is an opportunity to double down on the things that will still remain relevant and valuable in that post-intelligence, post-scarcity world!

Get fit, get strong, tinker and build, fix your own cars and house stuff, build an open source alohabot you can spin up an artifical mind in when they come online, learn to cook well, build a deck for your house, or a treehouse for your kids.

Also, focus on friendships, foster stronger connections, hang out with your friends more, ask them to invite other friends you haven't met, go to social events and parties, start throwing parties and get-togethers yourself, pick up a new hobby and make friends there.

Because you know what's not going to be counterfeited, even in a post-scarcity future?

Being fit and having good physical health

Real world friendships

Being able to entertain and throw really good parties

Being able to fix or build your own stuff

Being able to cook tasty things with whatever you have on hand

Building and making is a good part of that, and the thought processes you’re able to cultivate and inspire from making - from no longer being limited to what already exists and is for sale - is prime training for building skills and ways of thinking that will have value in a post-scarcity future where everyone will be able to create a much wider range of conceivable things.

So get out there and start exercising those skills!

Build, make, and create! Because it represents one of the finest parts of being human, and will still have meaning, even in a post scarcity future.

What did I leave out that you’d get from reading the book yourself?

If you are a maker yourself, or aspire to be one, I highly recommend the book. It’s by a maker at the literal peak of the field, and has many great stories, and more importantly, is a fine example of the distilled wisdom of decades of hard-learned lessons. You would get:

A lot more depth and context, and a good feel for his overarching philosophy as a maker, along with a ton of useful tips

A whole section on the theory and practice of various glues and epoxies

He has this amazing story of a builder class for 7 year olds where the teacher takes all the chairs away, then the kids go and try to make chairs themselves. The chairs fail right away, of course - so for each chair that fails, they take it back to the shop and study why, and brainstorm ways to fix it. The 7 year olds start carefully attending to the chairs in their lives, to understand why and how they’re put together the way they are. They iterate through a bunch of fixes to their chairs as they fail in various ways. At the end of it, each student ends up making an excellent hardwood chair, complete with planning ahead, precision, clamping overnight, joinery and glues, and much else. One of the finest examples of “learning by doing” I’ve run across for that age group.

Tons of fun anecdotes, the story of making a pretty cool Rube Golderg device he built for a Coke commercial, and pictures galore.

Driving big SUV’s and trucks around with only 1 person for nearly all personal trips (trucks and SUV’s are 80%+ of new car sales in the US as of 2022), aircon maxing when houses are empty, etc

Damn, you laws of thermodynamics!

Although it’s still in the same (crappy) rough range (Jungian in the linked chart) in terms of predicting life outcomes, surprisingly.

For an example, see here: https://imgur.com/a/hCvGMpf

Although given my Substack posting rate and my large and growing backlog of already written and scheduled posts, some portion of my former productivity is seemingly being channeled here.

Industrial Lights and Magic, the same shop that famously did all the Star Wars movie effects, from the very first movie.

Stuff you buy loses that special "new thing" glow pretty quickly, if you know what I mean. Stuff you've made yourself still gives you satisfaction when you use it months or years later, I've found.

I'm a big fan of bush-craft, primitive crafting and recreating ancient archaeological finds. I'm not especially worried about a lack of meaning if the world really does become post-sarcity, but that kind of thing will be almost completly AI-proof because the whole point is being self-reliant and making stuff yourself.

"The great majority of people consume and waste and destroy, and that’s pretty much it.

The average person buys junk and fast and other processed food for nearly all their meals when they’re already fat, they use a ton of energy as their default for basically no reason1, they buy a lot of stuff and throw away a lot of stuff, they never fix anything, and they never make or create anything." Are you alluding to something like bs jobs with this? Obviously most people have some kind of job that's at least ostensibly about producing stuff.

Do you keep a list of books you've read a la goodreads?