How Asia Works

I think many people know the broad strokes here - the Asian countries that have prospered and become developed countries after WWII instituted broad scale land reform, going from a 10% elite owning most land to 70% of people owning land, democratizing productivity ownership, leading to 50% higher yields as farmers poured more of their time and effort into their crops, because they enjoyed the upside as owners in a way they wouldn’t as tenants.

The increased productivity is important because it both feeds everyone without wasting precious forex reserves on importing food, AND stimulates demand because the farmers have more money to spend, and then you can bootstrap to manufacturing for local markets, and *then* you can bootstrap to manufacturing for export markets, yada yada.

It’s the developing country “success sequence:”

Do land reform to put land into lots of small farmers hands, who will then spend more time and labor to increase outputs and productivity per hectare1

Use that extra productivity to feed yourself and export, while you get into manufacturing via using the funds from increased exports

Ignore all economists, listening to or emulating only Prussians or Frederich List or the Japanese, as you cannily use tariffs, central bank export incentives, and export discipline to git gud at manufacturing

Use the money and economic growth from 3) to increase education and average incomes, and bootstrap up to a manufacturing + service economy + knowledge economy

Congrats, you’ve become a developed country!

The overall story is basically in the water supply by now, at least in the circles I’m in.

Probably the biggest thing that isn’t addressed by Studwell, or by anyone that I’ve run across, is what a country can do when it’s off the “success sequence” mainline.

Agriculture doesn’t matter to anyone now

What if you never underwent a meaningful land reform, and China ate all the manufacturing arbitrage in the world, and you’re stumbling along with agriculture a dwindling fraction of your economy? I’m not sure any country has actually gone “from third to first” under these conditions, and at this point, “land reform” may not even matter if your country’s agriculture is <10% of your GDP.

What would mainline economists recommend in this position? Almost certainly the same “Washington Consensus” that hasn’t yet resulted in any developing country achieving the ranks of “developed.” You know, fiscal discipline, tax reform, investing in education, zero tariff trade, no currency controls, privatization, deregulation, and all that.

Fine ideas if you’re already firmly on the developed path (roughly the latter half of stage 3 in Studwell’s success sequence), but seemingly not much help to actually developing countries. In fact, a recurring theme in why the “developing” SE Asian countries are still “developing” is that financial liberalization and currency controls *were* liberalized according to Washington Consensus recommendations, and it led to nothing more than elites printing themselves money and wasting that money on real estate and stock exchange bubbles.2

Who has “developed” successfully?

Moreover, it should be noted that the three countries that have actually successfully navigated the “developing to developed” pipeline recently (Ireland, Israel, and Chile in the late nineties / early two thousands) did NOT follow the success sequence, and never really saw the focus on manufacturing and export discipline that Studwell recommends.

And I genuinely wonder, now that China has essentially eaten most of the manufacturing arbitrage in the world, how a developing country is supposed to build up that capacity while competing with China, which has basically all the resources, FDI, and huge leverage in network effects, such that all your supply chain and logistics dependencies are easy and robust in China, but which would have to be built from scratch (or imported from China) in any country trying to follow the success sequence.

Effective panopticons exist now

Finally, I worry that as technology has progressed, the forces that have led to the various failures and revolutions that pry the fingers of current elites off the steering wheel enough to allow things like land reform or building a relatively non-corrupt and non-incestuous financial system,3 may no longer be possible.

I mean, elites are ultimately accountable to the masses because they can mass outside your walled compound and burn it down. But what if they can’t? What if spying technology gets good enough you can track every potential rebel and rabble rouser and coordination mechanism? Right now you can track them and pick them off one by one with black vans for “reeducation,” but what if technology got even better, and you were able to intelligently shape public discourse to damp the overall temperature and contours of public opinion to begin with? This world is basically here today, and China is happy to sell you the tech.4

A post-labor world is possible

Finally, in a world of better robotics and automated production, what if you don’t need your people at all? What if they shift from the “asset” column to the “liability” column once fully automated farm and factory technology packages exist? This world is probably not that far off, at least in relation to the decades long journey of countries economically developing.

Essentially, I’m worried that Studwell’s “success sequence” no longer exists as a meaningful route to economic development. The bottom of that ladder has fallen off (China will always beat you at manufacturing, at any step of the value chain), and the next 2/3 could fall off soon. The three countries (Israel, Ireland, and Chile) that successfully navigated the transition did so with special circumstances and backgrounds.

A look at the three winners

And what were those circumstances? What does “developed” even mean?

A country is considered “developed” if it has a per-capita-GDP of between $12-$15k, and has decent qualitative measures on health, education, and infrastructure.

So how did our three winners pull it off?

Ireland - being part of the EU and aggressively targeting multinational corporate FDI and headquarters location via favorable tax minimization laws. The “double Irish” and such.

Israel - a highly educated base population supplemented by highly skilled immigration, targeting high tech, military hardware, and software, with substantial FDI.

Chile - Pinochet basically pulled a mini Lee Kuan Yew after becoming dictator, outsourcing his economic decisions to The Chicago Boys, who put the economy on privatized and liberalized economic footing while pivoting to an export focus. Notably however, they didn’t focus on manufacturing or industrialization - the biggest exports are copper, wine, fruit, and fish.

There’s indications of higher human capital in all three as well. Chile had a 90% literacy rate vs the ~60% of nearby countries, a smaller indigenous population, and relatively high post WW2 European immigration.

Israel of course has a highly educated and capable base and immigrant population, with the Jewish people massively over represented in Nobel prizes, finance, and media success.

Ireland invested heavily in education, particularly STEM education, and this highly educated English speaking work force, coupled with the Irish Development Agency courting multinationals with low corporate taxes and good infrastructure, proved attractive enough to bring a lot of FDI.

None of them are manufacturing heavy, and none followed the version of Studwell’s “success sequence” that lifted Japan / Taiwan / Korea up to developed status. AKA heavy and targeted central bank investment, increasing manufacturing and industrial capacity with first tarrifs and foreign currency controls while nascent, and then a tight focus on export discipline as you liberalize the financial system.

To be fair, Studwell’s has literally titled his book “How Asia Works,” and none of those three are Asian countries.

Asian counterpoints

But what about Malaysia ($12k per capita GDP as of 2023)? Malaysia is right on the edge of being considered developed (a country is considered “developed” if it has a per-capita-GDP of between $12-$15k and has decent qualitative measures on health, education, and infrastructure), and it's actually SE Asian and didn't follow the success sequence - it never did extensive land reform, it has pushed on manufacturing, but 20% of exports and government revenue is oil and gas, and 23% of employment is tourism based. Malaysia was one of his “failure” cases in the book in terms of not doing land reform at all, and in terms of doing manufacturing wrong, but here they are.

Or how about Vietnam? It’s been explicitly and assiduously following the Studwell success sequence since 1986. Exports are nearly 90% of the economy, and manufacturing has steadily grown in that time to be more than 25% of GDP. But in that nearly 40 years, it’s gone from roughly $700 GDP per capita to roughly $4,500 GDP per capita, a factor of roughly 6 improvement, whereas in their comparable periods of growth, Taiwan’s and Korea’s improved about 60x, and China and Ireland at least 12x (Vietnam’s growth is in line with historic Japanese and Israeli growth rates, which both started at a much higher baseline GDP per capita). If they can maintain this pace, and it’s worth pointing out that this pace slows down greatly in every country as the GDP base you’re growing from increases, they might make “developed” status by around 2040, roughly 60 years after starting - but everyone else hit it after 20-40 years, and from higher baselines.

It makes one wonder how applicable Studwell’s success sequence can be today, in a world where China’s productive capacity is roughly equal to the entire developed world’s, and agriculture has already fallen significantly as a percentage of GDP for the remaining “developing” countries.

It makes you wonder if there IS a real recipe for lifting developing countries up to developed status. The Studwell “success sequence” looks more and more like a contingent historical recipe to me, than a reasonable playbook for economic growth and prosperity overall.

Certainly, even on current paths worldwide economic growth continues, and at some point we would expect SE Asia and central and South America and Africa to exceed the $12-15k USD gdp-per-capita threshold that might put them in the ranks, without any changes.

Or AI and better robotics could entirely counterfeit most human labor entirely, lopping off the bottom 2/3 of the ladder, leaving developing countries perpetually struggling as their elite become trillionaires.5 After all, the bottom of that ladder is so hard to navigate, that only 3 countries in the world (all non Asian) have ascended it in the last 30 years.

This is an argument that there will be an unusual amount of leverage and a chance to significantly impact the lives of billions of people in the next few decades.

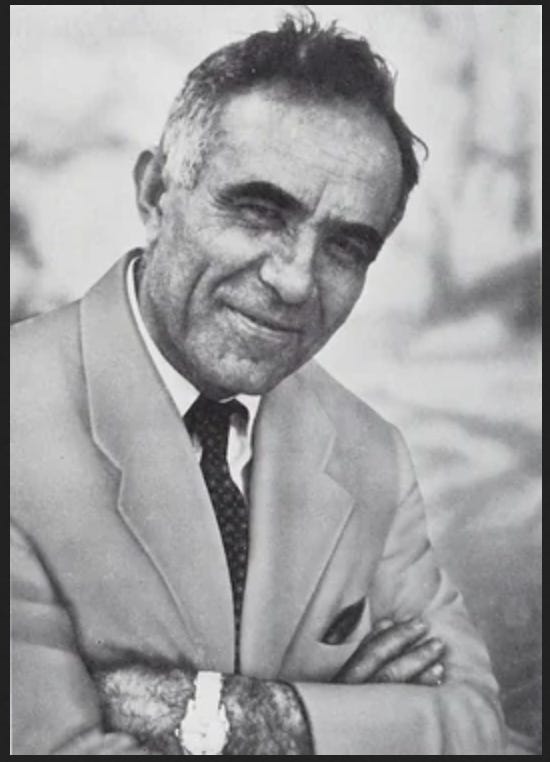

This is Wolf Ladejinsky. If Studwell’s book is portraying his impact faithfully, he probably deserves to be as venerated as Norman Borlaug in terms of positive impact on humanity. He was the key person on the US side pushing for land reform, when everybody else was relatively indifferent or actively opposed. Just back of envelope, he probably had a noticeable hand in creating the economic delta between Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, versus Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Burma, Laos, and Cambodia.

That’s 200M people about 7.5x better off in GDP per capita, or in USD terms, 200M people $30k better off per year. So just in one year, 6T of value. If he’s maybe 10% responsible (he’s probably more impactful than that), he’s chalking up 600B of value driven per year, with all the attendant quality of life increases, and lifespan and health increases, for those 200M people annually to his credit.

That’s a staggering amount of impact for somebody you’ve never heard of! Sure, this is attributing 100% of the gap to land reform and Studwell’s overall thesis, entirely neglecting leadership decisions, culture, and the actual hard work of those 200M people in terms of driving the delta - but even discounting and putting provisos anywhere you feel like, it’s a good bet that Ladejinsky has done more good than you could ever dream of, and more than many people that we publicly venerate for public impact like Borlaug or Edison or Kissinger or whomever.

And was he rewarded or recognized for it at all? No, of course not. The McCarthyites got him, and in 1954 he was booted from his government job at the Department of Agriculture for “security” reasons because he had three sisters in the now Soviet Union and had once worked as a translator for the American office of a Soviet trading firm after first arriving in the US. Womp womp.

Frederich List, of course, also deserves to be here for similar reasons, and for how instrumental he was to Japan and Korea’s policies while developing.

The takeaways are obvious - being a bureaucrat or economist at pivotal times can be surprisingly high impact. Usually this isn’t very relevant or actionable, because existing in interesting times isn’t really up to you.

But good news! We seem to be in interesting times, given the pace of AI and robotics improvement, and there’s a much-higher-than-usual chance that some great economic phase transition is going to happen over the next couple of decades for a number of countries.

The move to significantly automated production is probably the last chance to get “developing” countries on a good path to aggregate improvement, and it seems very likely that there will be a number of pivotal decisions in their temporal path to either losing the ladder entirely, or transitioning to “developed” status in an economics 2.0, automated production world. The leverage of being a bureaucrat, economist, or policy maker will probably never be higher from a human impact and EA perspective in the next decade or three.

An interesting thing about the increases in productivity - Studwell talks a lot about the higher-than-usual potential of the land in SE Asia, and the abundant water, representing a latent capacity to do really well farming productivity wise, which most countries roundly fail at living up to.

Indeed, if you’re used to more temperate places and have ever traveled to somewhere tropical like Hawaii or Singapore or the Philippines or Thailand, one of the things that most strikes you is how impossibly green and lush everything is. Life seems to be exploding from the ground in an absolute riot of verdant diversity and bounty, representing a profoundly deep well of fertility and growth potential. “Farming must be soooo easy here,” you think, envisioning crops springing out of the ground a couple times a year, with the abundant sunshine and rainfall allowing them to thrive and bustle at the efficient frontier of crop vitality.

It’s all a lie, incidentally. For all that it looks like the ideal growing environment, because so much STUFF is just growing everywhere, and for all that if you’re responsible for a given plot of land in any tropical space, you have to allocate actual time to machete-ing and chainsawing everything back regularly just to keep your land recognizably demarcated and usable, it’s a bit of a Potemkin village.

As we learn in Dirt, tropical soil is actually quite marginal, and more reliant than usual on fertilizers and pesticides and other modern boo-lights. This is because it’s poor in nutrients - all the nutrients are in the crazed verdant greenery you see everywhere, not in the dirt!

All that nice rain that occurs so frequently actually washes nutrients out of the soil, into deeper parts inaccessible to roots, or into the local rivers and watersheds. All that strong sunshine coupled with the rainfall actually weathers and degrades the soil.

Finally, that riot of thriving life is actually an intense competition of all against all, and the heat and sunlight and rain actually ensure that resources are snapped up as fast as they can be! Dead things decay faster, nutrients get sucked up more quickly to be used in the competition, and so on.

So what usually happens with tropical places is that a farmer will clear cut or burn a section of forest or plant life, have one good planting, and then the soil is depleted, and they have to use a lot of fertilizer to keep going. Pesticides and insecticides are necessary too, because pathogens and insects and weeds are all turbocharged by the same environmental features that make it a riot of greenery. All in all, farming in the tropics is much harder and more marginal than farming on grasslands.

But overall, Studwell is comparing to a baseline of technologically-mediated farming productivity in the success cases, so I suppose it’s fair to count the sunshine and ample rainfall as positives that should lead to more underlying productive capability.

As one example, when banking in Malaysia was liberalized, it just turned into real estate and stock market bubbles, with the stock market so overheated, the total capitalization was 4x the gdp prior to bursting, and traded more than the NYSE on some days.

Another interesting fact cluster - how elites are able to shape things to their enduring benefit. And here “elite” means “at the level of owning your own bank.” Keep in mind, this is in countries with roughly $2k gdp per capitas at the time. And if you *are* at that level, and if there has been no revolution (China, Taiwan), or war (Japan, Korea) with some much stronger outside country forcing real land redistribution, the land just doesn’t get redistributed, and all the IMF and World Bank financial liberalization policies just end with the elites hoovering up cheap money to build and consolidate local oligopolies.

A recurring theme for the failure cases of Asian development (Philippines and Indonesia, and to a lesser extent Thailand and Malaysia), is banks owned by elites using the banks and central financial system to glut themselves on cheap capital and build and consolidate oligopolies at home, rather than doing the hard thing of building businesses selling internationally with export discipline.

https://www.iranintl.com/en/202202123131

Let’s deep dive into the incredibly incestuous elite politics and land ownership in the Philippines as a case study. If you want a picture of “entrenched elites with their hands firmly on the levers of power,” look no further than the Philippines.

Of the 9 presidents since 1960, 6 of them were direct parent - child relations (Ferdinand and Bongbong Marcos, Diosdado and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, Corazon and Noynoy Aquino), and all 9 families are related by marriage at the very least, except for Duterte, who was a friend of Marcos.

Some of the biggest land owning families, at least according to Studwell and Task Force Mapalad, are Cojuangco, Benedicto, Arroyo, Cuenca, Tan, Floirendo, Sebastian / Marsman, and Lopez.

Let’s rewrite that: Cojuangco (related by blood to two Presidents), Benedicto (Marcos crony), Arroyo (the literal family of two presidents), Cuenca (Marcos crony), Tan (Marcos crony), Floirendo (Marcos crony) , Sebastian / Marsman (secretary of Dept of Agriculture and President / CEO of Marsman banana company), and Lopez.

All of the “Marcos crony” appended families up there were literally prosecuted after Marcos’s deposal, and returned millions of dollars worth of assets they had bought / held for Marcos.

Worse, banks were essentially used as private piggy banks for prominent families. The central bank pursued IMF / World Bank and Washington Consensus approved policies such as giving discounted loans to smaller private banks (rediscounting), relaxed foreign currency controls, and other financial liberalization moves but rather than using that to shape policy towards industrialization or manufacturing, it was mostly used to enrich the various owners of the private banks (of the 33 banks, one of 33 elite families was majority owner), such that the central bank went bankrupt both in 1921 and 1949.

These were essentially negative discount rate loans. And what were they used for? Any old thing. Tobacco trading, coconut milling , stock trading, building internal media and telecom companies. Just as some examples, Danding Cojuanco used them and coconut export subsidies to grow his bank from 17th biggest to 4th biggest by assets within 7 years, Marcos used them to buy Manhattan real estate, and Benedicto, whose main businesses were telecom and media, used his so profligately half his bank’s assets were rediscounted loans, and his entire bank went into deep crisis within 5 years.