If I told you that we waste around a trillion dollars every single year while poorly executing on badly managed megaprojects around the world, what would your reaction be?

I’m sure the libertarians out there are *snerk*-ing quietly under their breath, and muttering about how that’s exactly what they would have expected. Government projects, amirite?

Maybe the pragmatists out there are saying “sure, government projects suck, but often there’s no other choice! Government is the only thing that will step up and do large projects with diffuse benefits but concentrated costs!”

But I hope what we ALL think on seeing that is: “wow, executing on large projects even 10% better would drive many hundreds of billions of value per year.” Bent Flyvbjerg is trying to help us do that with How Big Things Get Done.

But to even understand the benefits and costs, we need accurate numbers.

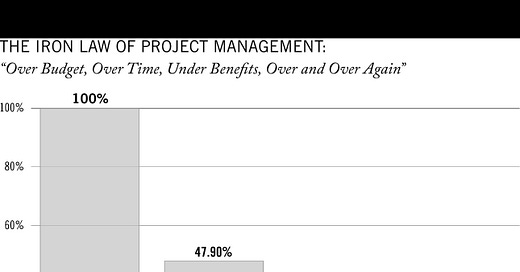

How often do big projects actually deliver on the benefits they promise?

How often do they overrun in cost or time, and when they do, how badly?

Before Bent Flyvbjerg, there was no way to answer these questions at scale.

No regulatory body or central database was keeping track of this information - it existed in a diffuse scattering of government agencies and contractor silos in various jurisdictions all over the world.

And yet, anyone paying the slightest bit of attention knows that the waste must be very significant.

This is the void that Bent Flyvbjerg stepped into. And who is Bent? A Danish economic geographer who has been studying and publishing about decision making, projects, and planning for a little over 2 decades.1

His research falls in three main areas: the philosophy and methodology of the social sciences, power and rationality in decision making, and megaproject planning and management. This book is the culmination of his research and ideas on project management and megaprojects.

So, enter Bent, into an informational void about megaprojects.

His team eventually pulls together data on more than 16k projects in 20 different fields in 136 countries, and finds that indeed, megaprojects essentially never come in on budget and on time, to deliver on the benefits promised.

The Iron Law of project management: over budget, over time, under benefits.

And you may be saying to yourself, “Duh! These projects are approved and driven by politicians, who definitionally have the competence and planning horizon of sea cucumbers. But if they put somebody *competent* in charge, they could be realistic and build in a healthy margin for time and cost overrruns.”

But no, Bent tells us, even this is woefully optimistic. How much margin would you build in if you were in charge? 10%? 20%, maybe even 30% if your persuasive skills are good enough to 1.3x the initial budget?

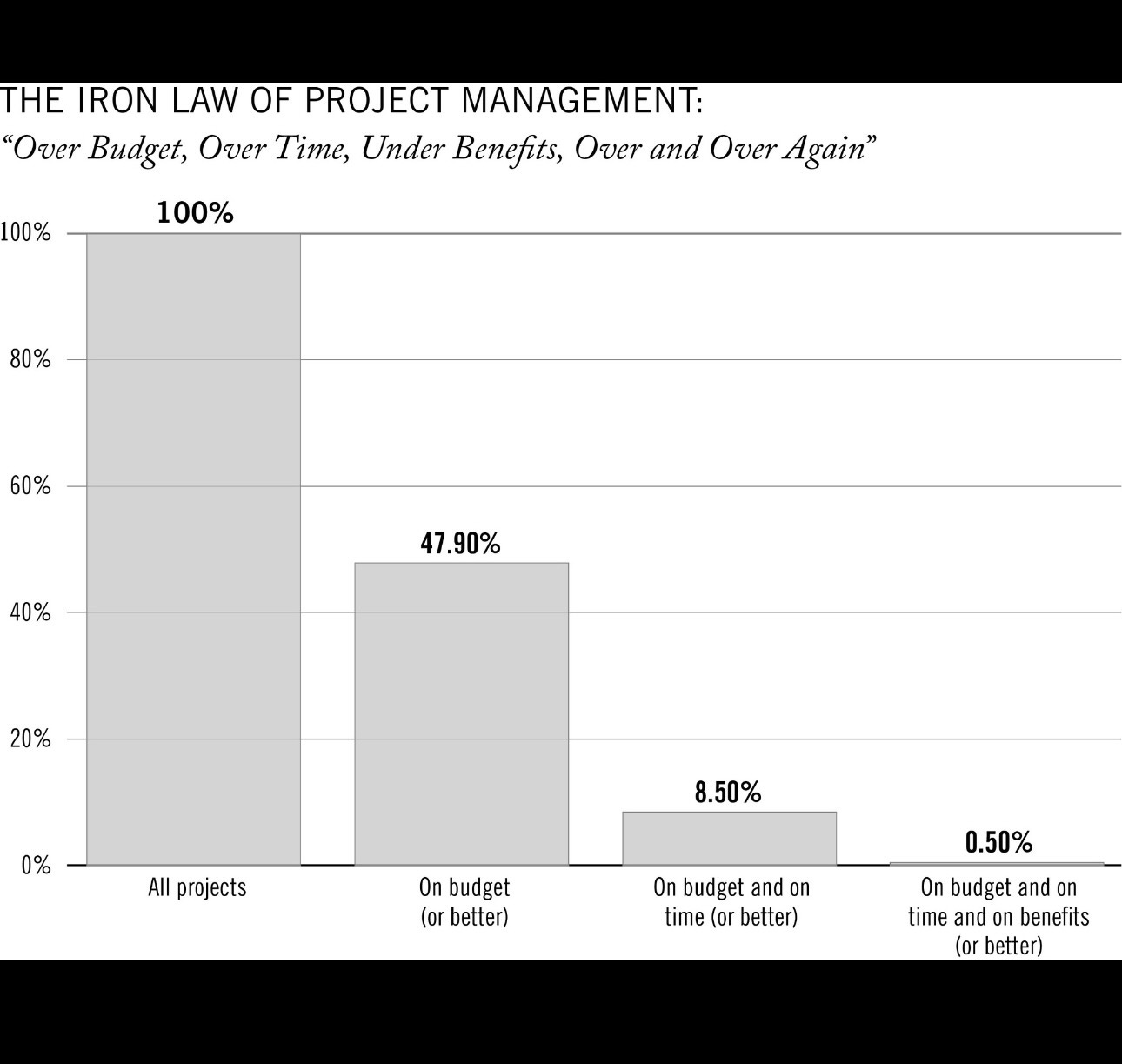

It is to laugh. The median cost overrun is actually 62%, so your 30% is basically nothing. But it’s even worse than THAT. Big complex projects live in Extremistan, not the median world. The distribution isn’t Gaussian, it’s fat-tailed, and if you’ve gone significantly over, there’s a decent chance you’re going to go hundreds of percents over now.

“To illustrate, 18 percent of IT projects have cost overruns above 50 percent in real terms. And for those projects the average overrun is 447 percent! That’s the average in the tail, meaning that many IT projects in the tail have even higher overruns than this. Information technology is truly fat-tailed! So are nuclear storage projects. And the Olympic Games. And nuclear power plants. And big hydroelectric dams. As are airports, defense projects, big buildings, aerospace projects, tunnels, mining projects, high-speed rail, urban rail, conventional rail, bridges, oil projects, gas projects, and water projects.”

Big Dig’s final cost was tripled. James Webb telescope went over 450%. Scotland’s parliament building went over by 978%!

And if you think that heading a relatively smaller, non-billion-dollar project will save you, it won’t. Fat tails are a symptom of complexity, and “projects” are typically defined by complexity, that’s why they’re projects.2

As Bent puts it: “If your project is ambitious and depends on other people and many parts, it is all but certain that your project is embedded in complex systems.”

Indeed, he uses several disastrous home renovations as small-scale demonstrations of this principle in the book.

In fact, let’s just put the data front and center - here’s how screwed you are, by field, if you’re heading a big project:

See how often these projects get out into the tails of >50% cost overrun? You get out in the tail ~33% of the time across these fields, and once you do, your average overrun is 185%!

Absolute madness!

I honestly think he wrote the book primarily for the consulting gigs, because it paints a tragicomic picture of seriously failed state capacity all over the world, and it paints Bent as one of the best people in the world to understand and help mitigate big project risk.

And he is brought on to consult in various projects across the world - the book is one long compendium of case studies, ranging from The Madrid Metro, to Heath Row’s Terminal 5, to Jimi Hendrix’ Electric Lady recording studio.

But all hope is not lost - he’s here to tell us the biggest reasons why these things fail, and to suggest mitigation strategies.

How do you know if a politician is lying?

Their lips are moving.

An old joke. Bent calls this factor “strategic misrepresentation.”

“In France, there is often a theoretical budget that is given because it is the sum that politically has been released to do something. In three out of four cases this sum does not correspond to anything in technical terms. This is a budget that was made because it could be accepted politically. The real price comes later. The politicians make the real price public where they want and when they want.”

—Jean Nouvel, Pritzker prize winning french architect

“If we gave the true expected outcome costs nothing would be built.’

— Anonymous engineer, regarding cost estimates

“We always knew the initial estimate was under the real cost. Just like we never had a real cost for the Central Subway or the Bay Bridge or any other massive construction project. So get off it. In the world of civic projects, the first budget is really just a down payment. If people knew the real cost from the start, nothing would ever be approved.”

-Willie Brown, former San Franciso Mayor and state assemblyman

I confess, I was tempted to conclude from the book that literally NO projects costing more than, say, 2 billion dollars should be allowed to be undertaken by any local, state, or federal governments, anywhere.

The benefits are nebulous and delayed, and the cost and time spent is always there in multiples. I think a just and fair cost / benefit analysis would eliminate 80% of them, maybe more.

Strategic misrepresentation is ubiquitous, and basically impossible to fix. Voters don’t pay attention on long enough timescales, the budget blowups can and usually do happen after they’re out of office, and nobody seems to actually care enough to do anything about it.

But then, there are that fraction of projects that would be worth it in a fair cost / benefit analysis, even with the (nearly guaranteed) chances of overrun. And trying to rage-quit and say that we shouldn’t let politicians near projects like these isn’t going to actually change anything, because they’re still going to con voters into approving them, and all that waste is still going to happen.

So the least we can do is understand what’s going wrong, and try to implement the things Bent suggests, to try to claw these projects back from the “impossible boondoggle” end of things.

I'll keep it short and sweet. Family, religion, friendship. These are the three demons you must slay if you wish to succeed in business.

—Mr. Burns

Fortunately, there’s a slightly different set of demons you must slay to embark on a large project successfully. The big 3 are Optimism, Uniqueness Bias, and Haste.

1. Optimism

“Unchecked, optimism leads to unrealistic forecasts, poorly defined goals, better options ignored, problems not spotted and dealt with, and no contingencies to counteract the inevitable surprises. Yet, as we will see in later chapters, optimism routinely displaces hard-nosed analysis in big projects, as in so much else people do.”

Optimism is a one-attribute System 1 wrecking ball.

“Widespread, stubborn, and costly,” as Kahneman puts it.

People reading this are probably already familiar with such concepts as System 1 vs System 2,3 inside vs outside view,4 and being poorly calibrated when estimating confidence about something.5

All too often when people estimate how long a project will take and what it will cost, they’re envisioning a best case scenario. You’re thinking about a kitchen remodel, so you add up the price of the flooring and tile and sinks and appliances, and you have a rough idea of the cost, right?

Wrong. You’re going to open the floor and see a rotted joist or water damage, you’re going to open a wall and see a wiring issue that needs to be fixed, and so on. The picture we create in our heads when estimating anything tends to be overly rosy and optimistic. But real life is rarely the best case, and that leads to cost and time overruns.

For these reasons and more, optimism is one of the first demons you must slay if you want to actually deliver on a big project.

2. Uniqueness bias - take the outside view

Everyone thinks their project is unique. Instead of seeing the class as “kitchen renovations,” they think of it as “kitchen renovations with granite countertops and German appliances in high-rise condominium units located in my neighborhood.”

This is mistaken, and at the wrong level of detail for this stage of a project. Taking the outside view and choosing the right reference class is the first step towards understanding actual time and cost expectations.

Another “outside view” is choosing things that are Lindy.6 People often want to do something “biggest” or “fastest”, but it’s usually a mistake, and is going to require “bespoke” and “custom” innovation and technologies, which is definitionally going to take more money and time.

And technology itself is better when it’s Lindy.

“The German philosopher Friedrich von Schelling called architecture “frozen music.”[9] It’s a lovely and memorable phrase, so I’m going to adapt it: Technology is “frozen experience.”

“If we see technology this way, it is clear that, other things being equal, project planners should prefer highly experienced technology for the same reason house builders should prefer highly experienced carpenters. But we often don’t see technology this way. Too often, we assume that newer is better.”

In technology, “new” or “unique” is treated as a selling point, not something to avoid. This is a big mistake that planners and decision makers make all the time.

On a personal note, I strongly agree and wish somebody would tell this to all the infinite hordes of “hang on, I need to download 20mb of random JavaScript libraries from 15 different sources to load a home page” Web 2.0 sites.

4. Haste - Think slow, act fast, not the other way around

Planning is cheap. It involves paper or computers, you don’t have expensive construction crews and equipment eating into your burn rate every day, and you can try out and iterate thousands of ideas and tweaks for little cost. In the ideal world, you would spend a long time planning, and a short time executing.

Yet, everyone hates planning. The thing people get wrong most often is doing this the other way around, and acting fast without a real plan, usually because they want to show “progress” for political or “optics” reasons.

A bias towards action is a very important and valuable thing, and advocated for by no less than Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Mark Zuckerberg, among others.

But one important detail - it’s a bias for “reversible” action. For important non-reversible actions or decisions, it pays to actually think things through. Most projects have non-reversible actions and decisions, and they are often front-loaded.

People hate thinking. They *hate* it! It doesn’t matter if billions of dollars, a promotion, or their very career might be on the line, most leaders see planning as “wasted effort,” especially in a time crunch, and would rather act and have tangible progress to show. This is one of the most common mistakes, and it leads to cost and time overruns.

“Planning is pushing the vision to the point where it is sufficiently researched, analyzed, tested, and detailed that we can be confident we have a reliable road map of the way forward.”

Once you have your plan, act fast.

According to Bent, an unfinished project exists in a liminal space that’s subject to various black swans, and the longer the window of the project’s timeline is open, the greater the chance of a black swan crashing through that window. And the black swan could be anything - a hurricane or earthquake, a pandemic, a strike, a major political change, a tunneling mishap, whatever. His point is, there’s a seemingly infinite array of these things that can come along and throw cost-and-time doubling spanners into the works, and the faster you’re able to execute and close your window, the safer you’ll be.

So how to shorten your window? Set ambitious timelines, drive your people hard, commit yourself to 80 hour weeks, and beat the galley drum as hard as you can?

I mean, that’s what *I* would do if I were trying to shorten the window, but Bent urges us to reconsider. He then points out to a handful of notable projects that were rushed and ended in disaster and deaths, but honestly the main complaint there sounds more like “incompetence” rather than “ambitious timelines.” Certainly, only be ambitious and fast to the extent you can execute competently.

He doesn’t really suggest a method to “go faster” in the end, just vaguely recommends it, then points at some disasters stemming from incompetence to caution you not to do that. So sure, good advice. Be competent AND fast.

If you’ve truly slain those three demons, then you’re well on your way.

The following are the rest of the heuristics he recommends when thinking about and tackling a big project.

4. Ask why

One of the most frequent factors in project failure is starting a project with an answer in mind. “I want to remodel my kitchen.” or “I want to build a bridge to connect the mainland and this island.”

He urges instead to ask why.

As an example, regarding the mainland and island:

“Picture politicians who want to connect an island to the mainland. How much would a bridge cost? Where should it be located? How long would it take to build? If they discuss all this in detail, they are likely to feel they have done excellent planning when, in fact, they started with an answer—a bridge is the best solution—and proceeded from there. If they instead explored why they want to connect the island to the mainland—to reduce commuting time, to increase tourism, to provide faster access to emergency healthcare, whatever—they would focus first on the ends and only then shift to discussing the means for achieving those ends, which would be the right order of things. That’s how new ideas surface:”

“What about a tunnel? Ferries? A helipad? There are lots of ways to connect an island with the mainland and meet a need. Depending on the goal, it may not even have to be a physical connection. Excellent broadband service may do what is required, and more, at a fraction of the cost. “Connecting” the island might not even be necessary or advisable. If access to emergency healthcare is the concern, for example, the best option may be installing that service on the island.”

As he tells us, “Developing a clear, informed understanding of what the goal is and why—and never losing sight of it from beginning to end—is the foundation of a successful project.”

I’ve seen this myself many times - there’s some problem, a meeting is called, and some person has an idea for a solution. That idea becomes an anchor point, and then all the rest of the effort - months of effort from tens or even hundreds of people - are going to be turned towards that end. But there’s a good chance the one idea some random person in one meeting had isn’t the best solution - in fact, that’s almost certain to be true. People are terrible at getting exactly the right answer the first time.

But people hate indecisiveness, they hate not having a direction, and they hate planning. So any random idea thrown out by any given individual in a meeting has a chance to tie up and direct tens or hundreds of person-months towards whatever random solution, because people rarely try to do better.

One of the practices Bezos instituted at Amazon is writing the press release and FAQ first, before you ever start on the project.

“Projects are pitched in a one-hour meeting with top executives. Amazon forbids PowerPoint presentations and all the usual tools of the corporate world, so copies of the PR/FAQ are handed around the table and everyone reads it, slowly and carefully, in silence. Then they share their initial thoughts, with the most senior people speaking last to avoid prematurely influencing others. Finally, the writer goes through the documents line by line, with anyone free to speak up at any time.

“This discussion of the details is the critical part of the meeting,” wrote Colin Bryar and Bill Carr, two former Amazon executives. “People ask hard questions. They engage in intense debate and discussion of the key ideas and the way they are expressed.”

The writer of the PR/FAQ then takes the feedback into account, writes another draft, and brings it back to the group. The same process unfolds again. And again. And again. Everything about the proposal is tested and strengthened through multiple iterations. And because it’s a participatory process with the relevant people deeply involved from the beginning, it ensures that the concept that finally “emerges is seen with equal clarity in the minds of everyone from the person proposing the project to the CEO. Everyone is on the same page from the start.”

People are terrible at getting things right the first time. But we’re great at tinkering. Wise planners make the most of this basic insight into human nature. They try, learn, and do it again.

Finding the “why” is the way to do that better.

Frank Gehry starts with the question “why are you doing this project?” And from there, “With no motive but curiosity, he explores the client’s needs, aspirations, fears, and everything else that has brought them to his door.”

We would do well to follow Gehry and Amazon.

5. Mitigate fat tails

Deep dive into your pool of risks to better understand them.

“We identified roughly a dozen of those and found that projects were undone by the compound effects of these on a project already under stress. We found that projects seldom nosedive for a single reason.”

When called in to consult on an ambitious high speed rail project in the UK, Bent’s team found on digging into past projects that archeological delays were able to act as Black Swans, and the risk was bigger the bigger the project was.

This is because if you get one archeological find, it’s fine - you hire an archeologist, they start processing the find, and you at least have a sight line to progress. But what if your project is big enough to find two? Or three? Pretty quickly, you run out of qualified archeologists who can both lead a dig AND are available for hire right that moment. And then you’re trapped. Zero progress, zero line of sight to progress.

What was the solution?

“Put every qualified archaeologist in the country on a retainer. That’s not cheap. But it’s a lot cheaper than keeping a multibillion-dollar project on hold.”

Mitigate early delays - many people don’t think of them as a problem, but they’re highly correlated with black swan blowups. People don’t worry about them because they’ve happened early in the project - there’s lots of time left before the deadline to work harder, or get smarter about something. But that’s not how it works in the majority of cases - an early delay opens you up to further delays and complications, and complex projects are more likely to snowball out of control in general than be amenable to working harder or smarter to make up lost time.

“After dealing with archaeology and early delays, we had ten more items on the list of causes of high-speed rail black swans, including late design changes, geological risks, contractor bankruptcy, fraud, and budget cuts. We went through one after another, looking for ways to reduce the risk.”

These were the specific risks for high speed rail - he urges people to dive into and understand the specific risks of past projects to understand the risk profile for your own type of project. Do a pre-mortem, ideally informed by data from past projects. Do post mortems on past projects if you can. Talk to people who were involved direclty to get the inside story.

“As with reference-class forecasting, the big hurdle to black swan management is overcoming uniqueness bias. If you imagine that your project is so different from other projects that you have nothing to learn from them, you will overlook risks that you would catch and mitigate if you instead switched to the outside view”

6. Hire a master builder

If you can only do one thing right, this should be the one to choose. Buy once, cry once. Even if the best person or team is expensive, how much more expensive is the potential 1.5x to 5x-ing in costs and time that most projects usually see?

Tacit knowledge, the knowledge you get by doing, is incredibly valuable, and more valuable the more complex the project.

“The simple solution, whenever possible, is to hire the equivalent of Frank Crowe and his team or Gehry and his. If they exist, get them. Even if they are expensive—which they are not if you consider how much they will save you in cost, time, and reputational damage. And don’t wait until things have gone wrong; hire them up front.”

7. Get the team right

But what if you can’t hire Frank Gehry? You need to get the team right, and build a high performing team. What characterizes a high performing team?

“We perform at our best when we feel united, empowered, and mutually committed to accomplishing something worthwhile.”

Yes, you can sell the vision to the people at the top - but will the people on the front lines buy in? Usually not, especially in construction. He had a great case study of one megaproject that got this right, the Terminal 5 construction project at Heath Row airport.

The company in charge was BAA, and they were determined to do it right. Instead of just hiring firms and overseeing work, they took on active leadership roles and shared risks.

In one situation where two contractors were potentially at loggerheads because the work of one could interfere with the other:

“BAA intervened. It changed its contract with Harper’s company to a cost-reimbursable arrangement with a percentage profit on top when milestones were met.”

They also didn’t follow a “lowest bid” policy, because that’s often a recipe for getting somebody inexperienced, without a real plan, who hasn’t done this before and is underbidding just to get a foot in the door.

“lowest bid” does not necessarily mean “lowest cost,” so rather than follow the common practice of hiring the lowest bidders, BAA stuck with companies it had worked with for years and that had proven their ability to deliver what BAA needed.”

Finally, at the actual boots-on-the-ground level, BAA knew that having buy-in was important. They had extensive branding on all PPE and crew jackets, to try to form a cohesive identity.

“Identity was the first step. Purpose was the second. It had to matter that you worked for T5. To that end, the worksite was plastered with posters and other promotions comparing T5 with great projects of the past: the partially completed Eiffel Tower in Paris; Grand Central Terminal under construction in New York; the massive Thames Barrier flood controls in London. Each appeared on posters with the caption “We’re making history, too.” When important stages of T5 were completed, such as the installation of the new air traffic control tower, they went up alongside the Eiffel tower.”

“The workers brought their usual cynicism to T5, Harper said. “But with that site, within, if not forty-eight hours, a week maximum, everybody had bought into the philosophy of T5. Because they could see T5 was implementing what they said they would do.”

Because they didn’t just put up some cheap posters and call it a day, like many places would. They made actual investments and effort. They had world class facilities for the workers - the canteens and toilets were the best many had ever seen on a job site.

If you were a worker and needed something, you got it. Goggles scratched? Get a new pair. Gloves are soaking wet? New pair. A tool broke? Get a new one.

They sat down and collaborated with workers on design, workflow, and benchmarks for the things they were working on. Because the workers had helped come up with the benchmarks, they owned them and executed towards them. They fostered a culture of psychological safety - allowing workers to suggest different ways of doing things, and to complain and be heard.

It worked.

“I’m sixty years old. I’ve been in construction since I was fifteen,” said Harper, who has worked across the United Kingdom and in countries around the world. “I have never, ever seen that level of cooperation.”

Richard Harper - construction supervisor

And the extra expense of doing all this? T5 did overrun on costs by about 40%, but it wasn’t due to being too free with the googles and posters.7 And they DID come in on time in a multi-billion dollar airport construction project, so they didn’t have that crew running for years longer than initially planned.

8. Be modular

There’s a subset of big projects that aren’t at much risk of going over, the “fortunate five.”

“The fortunate five? They are solar power, wind power, fossil thermal power (power plants that generate electricity by burning fossil fuels), electricity transmission, and roads.”

The thing that characterizes these is that they are modular - there’s a lot of lego-like pieces, and scale or doing it bigger is mainly a matter of linking together more of those pieces.

Modularity was key to the Empire State Building’s success - the heads of the project had a laser-focus on staying on budget and schedule, adapting designs to conditions of use, construction conditions, and to facilitate speed of erection.

Even with an 18 month deadline,8 they spent their time planning:

“the architects knew exactly how many beams and of what lengths, even how many rivets and bolts would be needed. They knew how many windows Empire State would have, how many blocks of limestone, and of what shapes and sizes, how many tons of aluminum and stainless steel, tons of cement, tons of mortar. Even before it was begun, Empire State was finished entirely - on paper.”

The pace increased steadily. From a floor in a week, to 3 floors, 4 floors, 7 floors a week - at the peak, they were doing 14 floors in ten days.

On modularity, the floors were designed to be as similar as possible, with many being identical, which meant that workers repeated work and learned, and this allowed them to keep accelerating that breakneck pace. The Empire State Building finished on time and on budget.

“Repetition is the genius of modularity; it enables experimentation. If something works, you keep it in the plan. If it doesn’t, you “fail fast,” to use the famous Silicon Valley term, and adjust the plan. You get smarter. Designs improve.”

9. Cultivate relationships and make friends

You know when you really need a friend in the right place, or a good relationship based on trust and mutual respect? When things are falling apart and tensions are rising.

You know when it’s possible to make those friends or foster those relationships? It’s not in times of tension and finger pointing.

The best time to establish good relationships is before embarking on a big project - the next best time is in the sunny days right after the project has started. Get good at fostering relationships of mutual trust and respect. Get good at making friends across business silos, job levels, and reporting chains. It could be the thing that saves your project.

10. The biggest risk is you

Demonstrate epistemic humility and self-examination, because if you’re involved in leading a big project, you’re likely to participate in some or all of these sins.

The biggest factor in most of these failure modes is bias and sloppy thinking, and wanting to make “progress” for political or optics reasons. You’re subject to all of those things, just like everyone else. But, alone in literally all the world, you ALONE can do something about it, and notice it, and try to do better.

11. Say no and walk away

A vastly underrated option. If somebody is trying to get you to head a project that you know is going to be a poorly run charlie foxtrot with zero chances of winning, say no. Walk away. It’s not worth the stress, aggravation, finger pointing, and recriminations. If you’re being forced to do this by your boss, start putting your resume out NOW.

And if that’s not an option, do whatever you can to mitigate the backsplash by following the checklist here.

So what’s the 8 step checklist to successfully tackling a big project?

Ask why, explore different answers and solutions, and decide on the overall goal of the project only after actually thinking about it deeply.

Eschew haste - Develop the plan iteratively and at length using experiments, simulations, and experience.

Eschew optimism and uniqueness bias - Mitigate risks and forecast outcomes by looking at real-world performance of past projects.

After all that, you have done your slow thinking and you have a plan worthy of the name. Now it’s time to act fast and deliver.

Assemble your team of master builders, the best team you can get.

Communicate the vision and get buy in from all levels.

Establish solid friendships and working relationships.

Modularize whatever you can.

And finally, deliver.

And if you’re ACTUALLY doing a mega project, and harking back to “assemble a crack team,” hire Bent as a consultant - that was my own biggest takeaway from the book. Not only does he have the biggest project database in the world, he has the real-world skills of having consulted on a lot of other mega projects.

What else would you get from reading the book yourself?

Case studies, case studies, case studies - so many case studies. In every industry, of every size, and often apropos and compellingly told.

Many more supporting examples for each of the points above.

He has a neat little “nuclear is not the answer” aside where he takes the usual objections “it’s all NIMBY, stifling regulation, and environmental study obstacles” and shows cases in China where none of this was true and nuclear got beat handily by other power modes on pure economics.

H-index of 78, many publications in Harvard Business Review, and the first BT Professor and inaugural chair of major programme management at Oxford’s Said school of Management

And if you think most projects are hamstrung and blow up because of stifling regulation, NIMBY, environmental impact studies, obstructionary lawsuits and the like, I’ve got news - even in China, which has none of those issues, projects run into the same cost and time overruns. The Three Gorges Dam project came in around 4x the initial budget, and 3 years late.

System 1 is immediate snap judgments, System 2 is slower and more rigorous evaluation where you think about and weigh pros and cons

“Inside view” is where everyone starts by default - you’re a unique person doing unique things. “Outside view” is stepping outside of yourself to the generic reference classes outside people would use. You’re not unique, you’re an X working in the Y industry. You’re not tackling a one-off modeling infrastructure transition to AWS and Kubernetes that needs to meet several requirements unique to your business, you’re doing a cloud migration. Outside view is stepping out of the weeds and using broader and more generic categories, in other words.

“In one study, researchers asked students to estimate how long it would take them to finish various academic and personal tasks and then asked them to break down their estimates by confidence level—meaning that someone might say she was 50 percent confident of finishing in a week, 60 percent confident of being done in two weeks, and so on, all the way up to 99 percent confidence. Incredibly, when people said there was a 99 percent probability that they would be done—that it was virtually certain—only 45 percent actually finished by that time.”

The Lindy Effect refers to the fact that the longer something has existed, the longer it is likely to continue existing. If something (like a book or a piece of technology) has been around for 100 years, it’s more likely to survive another 100 years than something that has only existed for 1 year.

They cite “complexity” and having to build some additional road and railway infrastructure.

An interesting tidbit from the book: “The word deadline comes from the American Civil War, when prison camps set boundaries and any prisoner who crossed a line was shot.”