Doping is ubiquitous in high-level sport.

Lance Armstrong and the Tour de France is a famous case, but it’s much bigger than that. The NFL, the NBA, the MLB1 - ubiquitous. The Olympics? Ha! Just the Mclaren Report surfaced more than 1k athletes doping across 30+ sports in the 2014 Sochi Olympics, and that was only about RUSADA and Russia!2 Although most people on the outside think most sports are clean, on the inside it’s openly joked about.

More, doping has a hundred-plus year tradition in sport, and for most of that, from about the late 1800’s to the 1960’s, it was completely open and applauded!3

Why is doping ubiquitous?

Many reasons. Winning margins in elite sport are often out in the decimal places now - a tenth or sometimes a hundredth of a percent for a race. But doping can give you advantages on the order of 2-20%. It’s not hard to see why a factor that can put a thumb on the scale 100-1000x stronger than most winning margins might take off.

Not just that, but the stakes are really high, especially at the top levels. The difference between Tyler Hamilton and Lance Armstrong (both Postal team cyclists in early 2000’s Tour de France races) in earnings and net wealth was something like 100 fold, but the difference in times between them across entire seasons was on the order of ~2-3%.

The difference between a top athlete and a middle-of-the-pack athlete in net worth in the NBA (20-100x), MLB (10-30x), or NFL (10-100x) is significant, and that’s after you’ve reached the tippy-top of the profession - if you imagine the difference between a college or minor league player and a pro player, you can add a couple zeroes to each one of those.

Not just THAT, but these are elite athletes at the top of their fields. Their life is literally defined by how well they do in their sport, and it’s been the sole focus of all of their efforts for a decade or more, typically. Above and beyond money, they see themselves first as an athlete, as being good at their given athletic endeavor. They’ve exerted superhuman discipline and effort, repeatedly, every day, for years, attaining the top of their field - you think they’re going to turn down anything that could improve them by years-worths of effort overnight?

Literally every possible incentive structure is pointing at “dope, you fool,” and then as an addendum, societally we tack on “and do you swear on holy books to be a Knight of Purity, to be a role model to the young in all respect and particulars, and to abide by chivalric standards of yore?” And everybody pays lip service to that, because apparently that’s what you have to do, and then goes back to their rooms and pumps themselves as full of as many chemicals as they can get away with.

So, motivation is high. What about capability?

Doping and detection is an arms race, but not a very balanced one.

When it comes to EPO use in the TdF, use was pretty common at the top from the early nineties. But even a crappy test for it wasn’t developed and deployed until 2001, and that was immediately circumvented by changing how it was dosed. It then took another 7 years to come up with longitudinal monitoring and the “biological passport,” and even THAT was ridiculous, because the longitudinal monitoring was on a “doped” basis too (Tyler Hamilton in The Secret Race even relates needing to get some EPO and use it before a test to make sure he was still in his usual longitudinal range).

Why is this?

On the one side, you have a bunch of globe-straddling, win-at-all-costs, maximally disciplined professional athletes with many millions at stake spending money on the best doctors and chemicals and processes that money and science can come up with, and on the other hand you have government-or-sport-funded bureaucrats whose revenue and viewers (or patriotism and national pride) depends on exciting performances. Not hard to detect an imbalance in incentives and resources there.

And those doctors don’t come cheap - most of the TdF team doctors routinely made millions per year.

Finally, if everyone in that milieu is doping, you have no CHOICE but to dope, to play on a level playing field. If even only the top one or two competitors is doping, everyone else has no choice! The game theory is extremely clear. Say you’re all competing in this thing with <<1% margins deciding victory. Somebody with even a 1-3% edge is an unstoppable colossus!

In fact, the TdF, and sport in general, is full of such moments:

In stage 14 in 2001, the French Festina team performed a circus strongman act the likes of which nobody had ever seen - at the foot of the 21.3-kilometer Col du Glandon, all nine Festina riders rode to the front, then went full bore, revving to unimaginable speed and carrying that speed over the climb of the Madeleine and into Courchevel.

In the spring of 1994 at the Flèche Wallonne race, three Gewiss riders simply rode away from the rest of the field at an unthinkable speed. In the cycling world, this type of team domination had never happened before; it was the equivalent of an NFL team winning a playoff game 99–0. In addition, seven of the race’s top eight finishers were all Italian, demonstrating that EPO innovation, like the Renaissance, began in Italy and traveled outward.

Bjarne Riis - for most of his career, Riis was a decent racer: solid, but rarely a contender in the big races. Then, in 1993, at twenty-seven, he went from average to incredible. He finished fifth in the 1993 Tour, with a stage win; in 1995, he finished the entire TdF on the podium. By 1996, some observers believed he might even be able to defeat the sport’s reigning king, five-time defending champion Miguel Indurain, and he did, he won the 1996 TdF.

What about Barry Bonds, Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa destroying the home run records?

Ben Johnson, a middle-of-the-pack Canadian sprinter, dominating heavy favorite Carl Lewis in 1988?

Lyle Alzado gaining ~40 pounds of muscle seemingly overnight and dominating in the NFL in the 70’s and 80’s?

Roger Clemens coming back in his forties and racking up award winning seasons?

All doping.

And if a middle-of-the-pack player can move from the middle to the top, everyone else has to dope to preserve the same relative rankings. And so it comes to pass. From Tyler Hamilton’s The Secret Race:

“In some ways, it’s depressing. But in other ways, I think it’s human. One thousand mornings of waking up with hope; a thousand afternoons of being crushed. A thousand days of paniagua, bumping painfully against the wall at the edge of your limits, trying to find a way past. A thousand days of getting signals that doping is okay, signals from powerful people you trust and admire, signals that say It’ll be fine and Everybody’s doing it. And beneath all that, the fear that if you don’t find some way to ride faster, then your career is over. Willpower might be strong, but it’s not infinite. And once you cross the line, there’s no going back.”

In fact, one reason a lot of the players implicated in doping scandals are top players (Armstrong, Clemens, Bonds, Sosa, McGwire) is that when you’re a top player and you add a “doping” performance margin on top, it’s so clear that you’re performing at a superhuman level, even normies start suspecting something is up, and the regulatory bodies feel they have to crack down for the sake of appearances.

Jose Canseco in Juiced:

“Have other superstars used steroids? If you don't know the answer, you've been skimming, not reading. The challenge is not to find a top player who has used steroids. The challenge is to find a top player who hasn't. No one who reads this book from cover to cover will have any doubt that steroids are a huge part of baseball, and always will be, no matter what crazy toothless testing schemes the powers that be might dream up.”

Doping isn’t about a lazy-man’s easy road to greatness. Hamilton again:

“People think doping is for lazy people who want to avoid hard work. That might be true in some cases, but in mine, as with many riders I knew, it was precisely the opposite. EPO granted the ability to suffer more; to push yourself farther and harder than you’d ever imagined, in both training and racing. It rewarded precisely what I was good at: having a great work ethic, pushing myself to the limit and past it.”

Doping regulatory agencies are weak and easily bought off

Did you know that Lance Armstrong blew hot on a doping test clear back in 2001, in the Tour of Switzerland? This was only 2 TdF wins into his 7 win record.

Why didn’t it lead to any scandal or press? Armstrong phoned the head of the UCI, they came to an arrangement, and everything was quietly hushed up. The lab that termed his sample suspicious ended up with donations of around $125k and a new blood testing machine, and he went on to win another 5 TdF’s.4

Why might this be? Armstrong WAS the TdF at this point, even 2 wins in - the amount of attention and money in the sport literally increased by 20x between 1980 and 2010 (Armstrong’s TdF wins were 1999-2005), and most of that increase was in broadcast rights, which generally constitute 50% or more of TdF revenue. Lance Armstrong - the guy who was a top level cyclist, got stage IV, multiply-metastasized, “you are definitely dead” cancer, beat it, and came back even better and stronger than before - was a publicity machine, and everyone involved knew it - EVERYONE in the biking world got more attention and money because he was in it. The TdF was never even televised in America, the largest and most profitable media market in the world, before Armstrong, they only ever showed highlights and clips - and Armstrong brought America in, and much more.5

Just to give you an idea, for even middle-of-the-pack players, salaries went from something like 30k annually to 300k annually over the 1990 - 2010 span (top players get many millions per year in salary, not to mention sponsorships).

Doping is GREAT for sports overall. One thing people love seeing is times getting faster, home runs flying farther and more often, higher jumps, faster sprints, and athletes performing at increasingly higher levels.

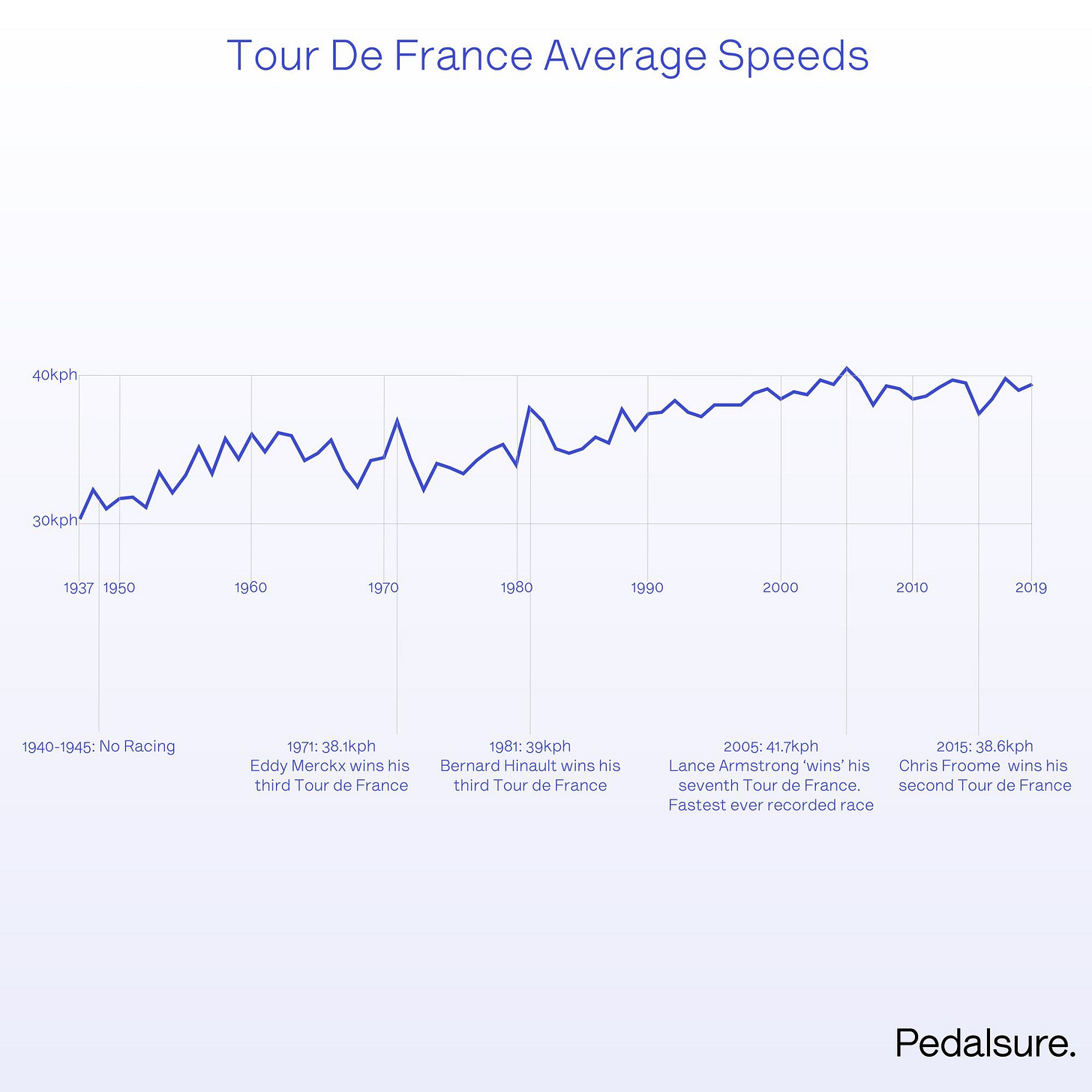

Look at this graph - in particular, look at the literally incredible uptick in average speed between 1990 and 2005.

That upward swing is directly correlated with excitement, engagement, sponsorships, tv viewers, in-person spectators, and revenue in your sport.

Those areas where you see big dips? Around 1967, 1971, and after 2005?6 Those are doping crackdowns - first cracking down on speed and opiate use (with a lag between countries and specific testing regimes explaining the two drops in the 60’s / 70’s), and the 2005+ drop is Armstrong retiring and them starting to use “biological passports,” or longitudinal measures of various metrics per athlete, and stricter EPO tests.

But do you know what else happens with big dips? Public engagement and excitement (and so viewership and revenue) is down. Anti-doping crackdowns are buzzkills, downers, vibe killers.7 Why do these guys suck compared to the athletes of just a year ago? Well, everyone was doping a year ago, and it takes a while for the teams to adapt to the newer testing regimes. But adapt they do - you see speeds climb steadily upwards after every drop, and record-shattering home run records bounce back after every scandal.

Jose Canseco:

“Is it cheating to do what everyone wants you to do? Are players the only ones to blame for steroids when Donald Fehr and the other bosses of the Major League Players' Association fought for years to make sure players wouldn't be tested for steroids? Is it all that secret when the owners of the game put out the word that they want home runs and excitement, making sure that everyone from trainers to managers to clubhouse attendants understands that whatever it is the players are doing to become superhuman, they sure ought to keep it up? People want to be entertained at the ballpark. They want baseball to be fun and exciting. Home runs are fun and exciting. They are easy for even the most casual fan to appreciate.”

Because of these dynamics, the general vibe at most anti-doping agencies is “you pretend not to dope, and we’ll pretend to test you.”

Tyler Hamilton again:

“DURING MY CAREER, JOURNALISTS often used the term “arms race” to describe the relationship between the drug testers and the athletes, but that wasn’t quite right, because it implied that the testers had a chance of winning. For us, it wasn’t like a race at all. It was more like a big game of hide-and-seek played in a forest that has lots of good places to hide, and lots of rules that favor the hiders. So here’s how we beat the testers:

• Tip 1: Wear a watch.

• Tip 2: Keep your cell phone handy.

• Tip 3: Know your glowtime: how long you’ll test positive after you take the substance.”

“What you’ll notice is that none of these things are particularly difficult to do. That’s because the tests were very easy to beat. In fact, they weren’t drug tests. They were more like discipline tests, IQ tests. If you were careful and paid attention, you could dope and be 99 percent certain that you would not get caught.

Bernard Kohl:

“Bernhard Kohl, an Austrian cyclist who finished third in the 2008 Tour de France before being suspended for a blood booster and stripped of the result, told The New York Times, “I was tested 200 times during my career, and 100 times I had drugs in my body. I was caught, but 99 other times, I wasn’t. Riders think they can get away with doping because most of the time they do.”

Often the “testing” is done at prescribed times that are announced well in advance. Even the “random” tests are usually gentleman’s agreements to pretend to test you, but not too rigorously:

“The best way to hide, though, was simply by reducing glowtime to a minimum. Because the best, most liberating rule of drug testing is this: the testers can only visit you between 7 a.m. and 10 p.m.* This means that you can take anything you like, as long as it leaves your system in nine hours or less. This makes 10:01 p.m. a particularly busy time in the world of bike racers. If you’re in Spain, you’re twice lucky, because given the nocturnal Spanish customs (dinner often starts at 10:30 p.m.), the testers almost never turn up at 7 a.m.; it’s more like noon, or later. (One tester, a considerate older gentleman who lived an hour away in Barcelona, used to telephone the night before to make sure we were in town, so he didn’t waste a trip.)”

And if you’re “hot” when a more-rigorous-than-usual tester shows up at the door? You don’t answer the door! If you evade a tester more than three times you a get a “strike,” but that’s certainly better than testing hot. If you rack up three strikes, you get a small suspension, but if you ever test hot, you lose your entire career.

“Taking a strike wasn’t a big deal. Getting caught, testing positive, would have been a catastrophe: I’d lose my job, my sponsors, my team, and my good reputation. I’d jeopardize Postal, and the jobs of my friends. Due to the French investigation, our 2001 Postal contracts contained a clause that allowed Postal to terminate the contract of any rider who violated anti-doping rules. Like Lance and everybody else, I lived my life one slip-up, one glowing molecule, away from ruin and shame.”

In the limits, this went as far as the Eastern Bloc’s “State Plan 14.25” and the GDR, which were literally only testing the athletes to make sure they wouldn’t blow hot in the official Olympics tests, because doping was mandatory and top-down, affecting more than 10k athletes,8 and whose mandate included bribing and intimidating IOC testing officials to make sure their athletes weren’t caught.

This has been carried forward in today’s Russia - the sample tampering and manipulation that came out when a top RUSADA anti-doping official defected to the US and gave a lot of details on the Russian doping program for the 2014 Sochi Olympics resulted in the Mclaren Report confirming that more than 1,000 athletes were involved, and that there were systematic processes put in place by RUSADA to switch dirty samples with clean ones, including using chemical additives to eliminate all traces of banned substances (a similar additive was offered to Hamilton by one of his doping doctors).

This is just ONE country, by the way, that we happen to know about because a central organizational body did it in a widespread and systematic way that was whistleblown by somebody formerly at the top. It’s a lot easier to hide decentralized efforts undertaken by specific athletes on an individual basis - and if you look at overall margins, those doped Russian Olympians aren’t tanking on every other Olympic country with huge margins, they’re close to or underperforming most other countries,9 and I’ll leave it to you to draw the obvious implications there.

There’s more ways to be smart about doping than there are to be smart about testing

Finally, and back to the 5-10 year gaps between a new doping innovation and any new testing innovation, there’s more ways to be smart about doping than there is to be smart about testing, for various reasons.

On the “doping” side you have literally top-in-the-world disciplined and talented people with millions of dollars in their budgets and tens of millions at stake hiring the very best doctors they can, and paying for the most cutting edge chemicals and techniques science can produce.

Unless you’re aware of specific doping methods, it’s difficult to come up with a test. But awareness obviously lags, because doping athletes and their doctors have the strongest possible incentives not to talk about or disclose any such knowledge. Dr. Michael Ashendon, the hematologist who helped develop EPO and transfusion tests in the late nineties, wasn’t aware of intravenous EPO microdosing until Floyd Landis explained it to him in 2010, more than ten years later, after Landis got popped and lost his career.10

Information is assymetrical in the other direction as well - doping doctors know the details and methodologies of the doping tests any regulatory body will do, and can specifically design against them in an adversarial way.

Think you can detect metabolites of various steroids? Oral Turanibol (CDMT) and tetrahydrogestrinone have got you covered, and went undetected for decades. The GDR went one step further, and pioneered micro-dosing and tapering protocols that ensured no athlete would glow hot on an IOC test. They also developed epitestosterone, which has no anabolic or androgenic effect itself, but alters your T/E ratios in the blood so you’ll reliably show negative for steroids when tested.11

Think you can measure ratios of different EPO metabolites in pee to catch people using synthetic EPO? Your athletes can microdose EPO intravenously, sleep in hyperbaric tents to change the ratios (or much easier, just use roxadustat, a HIF stabilizer that mimics altitude training), use pegylated EPO that isn’t metabolized via the kidneys (CERA), or use Dynepo or biosimilars that tests the same as human-origin EPO.

Finally, you can benefit from doping even if it was years ago

In practically every athletic endeavor, you benefit from more muscle mass, strength, more intensity, and more training hours.

Muscle and strength are self-explanatory, so I’ll focus on intensity and training. A huge part of elite performance, in fact THE distinguishing feature, is often better mental schemas and representations.12 The way you achieve those is with more intense training, and with more training hours overall.

Did you know elites train about 3x more than average participants?13

Doping allows you to put in more intense training, AND to put in more training hours and still recover well from them. So doping also allows you to hone the better mental schemas and representations that separate elite and sub-elite athletes, as well as improving muscle mass and strength. And once more muscle mass or better mental schemas and representations are built, they don’t go away, they’re yours as long as you’re using them, whether you’re still doping or not.

Remember how a 2% margin can mean the difference between “winning the TdF” and “not even on the podium?” Do you think training more intensely and with more volume over many years might be able to bump an athlete’s performance up 1-2%? There’s your answer.

So should we just give up and have “outlaw” leagues?

Obviously this whole system is dumb - everyone at the top levels is forced to dope by stakes and incentive structures and game theory, and everyone needs to risk their extremely lucrative and specialized careers to do so. When they get popped, it’s tragic - they not only lose their career and income and the ability to participate in the sport they love and have specialized their entire life around, everyone else left in their sport’s world, the athletes who were their closest friends and teammates and partners, generally cut off contact, and it’s entirely hypocritical because THEY’RE all doping too, and the difference between being popped or not is largely luck!

Most anti-doping agencies don’t even WANT to catch a bunch of athletes! Higher performance is good for everyone, it brings more viewers and revenue and ultimately more participants into the sports they all love and are part of, and is a direct demonstration of the bleeding frontiers of human excellence.

So why don’t we just give up the charade?

Here I have a second-order contrarian take, as against what my usual first-order contrarian take would be (ie “outlaw leagues for everyone!”).

Yeah, it’s all dumb. But it’s probably still useful.

The game theory and Red Queen’s Race dynamics around doping means that in the absence of ANY controls, everyone would be pushing up to and past the bleeding edge a lot more, and that would mean killing a lot more elite athletes in the prime of their lives, for no real benefit.

Hamilton on Lance Armstrong’s mindset (aka, the median “winning” mindset):

“He was incapable of being passive, because he was haunted by what others might be doing. This was the same force that drove him to test equipment in the wind tunnel, to be finicky about diet, to be ruthless about training. It’s funny; the world always saw it as a drive that came from within Lance, but from my point of view, it came from the outside, his fear that someone else was going to outthink and outwork and outstrategize him. I came to think of it as Lance’s Golden Rule: Whatever you do, those other fuckers are doing more.”

There are many examples of athletes ending up in the ER or dying from doing PFC’s, from bad blood transfusions, or from EPO.

Maruo Gianetti ended up in the ER after using PFC’s.

Jesus Manzano collapsed and nearly died on Stage 7 TdF from a bad blood transfusion, and had to be airlifted to a hospital.

18 Belgian and Dutch cyclists died between 1987 and 1990, due to heart attacks or strokes brought on by blood thickened from excessive EPO use.

Tom Simpson collapsed and died on Mount Ventoux in the 1967 TdF, from an amphetamine overdose and heatstroke exacerbated by the climb.

Prior to Simpson, in 1955 Jean Malléjac collapsed on Ventoux from heatstroke exacerbated by amphetamine overdose, but he was saved and was able to compete in the TdF again in 1956.

Also in 1960, Roger Riviere was taking Palfium “an opiate three times more potent than morphine” during the TdF, got so numb he couldn’t pull the brake levers, then flipped over a low wall and fell 60 feet, breaking two vertebrae at the age of 25, and living the rest of his life paralyzed.

Every one of these is tragic - an elite athlete in the prime of their life dying or seriously endangering their health just to stay competitive in a field of dopers (which I hope you understand at this point, is EVERY top-level athletic field).

If we ran “outlaw leagues,” this would be happening a lot more, because the winning mindset is always epitomized by Armstrong’s “Whatever you do, those other fuckers are doing more.”

So I’ll maintain that the farcical and blatantly gameable doping standards and regulatory bodies we have now are actually doing a fair amount of good. We don’t WANT outlaw leagues, because we don’t want a lot more elite athletes in the prime of their lives dropping dead.

What’s a reasonable compromise?

The REAL mitigable tragedy, IMO, is The Wall, where even though everyone dopes, anyone unlucky enough to glow hot on a test is formally Cast Out, never to sully the sport again, losing their career, their income, the sport they love and have built their entire life around, and their friends and social networks.

Frankly, that’s pretty messed up. Lance Armstrong was a generational athlete that was genuinely better than all the other cyclists he competed against. Yes, he doped, and so did all of the rest of them, and he still won 7 TdF’s and dominated the sport for a decade. Yes, he was an infamous asshole personally, who burned through every conceivable type of personal and professional relationship like matchsticks, but did you know he is personally responsible for raising many billions in funding for cancer research?14

Casting Armstrong out and costing him tens of millions of dollars in 2012 (7 years after retirement) didn’t clean up the sport, any more than casting Tyler Hamilton out and costing him millions in 2005 cleaned up the sport. Sure, times decreased for a year or two - where are they now?

The Wall forcing Jose Canseco to retire in 2002 before he could hit 500 home runs, and Barry Bonds to retire in 2008 didn’t stop doping in baseball (after all, didn’t A-Rod get popped in 2009, just a year later, and again in 2013?)

Elite sport isn’t clean-uppable, is the overall point I’ve been making here. The incentives and the game theory are too strong, and the capabilities on either side are too imbalanced, for that to be a realistic goal.

I think that having testing regimes does some good and limits the damage, but that we should be more forgiving of blowing hot. It shouldn’t be binary. It shouldn’t cost you your entire career to get unlucky one time out of hundreds. Set up a “three strikes” regime, and just pragmatically recognize that athletes are going to dope, but keep bounds in place so they’re not all killing themselves.

After all, this is an affordance that most sports already give to the top players. Armstrong first blew hot in 2001! He had an entire government investigation against him in 2010 by the same guy that investigated Barry Bonds, the MLB, and the NFL (Jeff Novitzky), and he was able to weasel his way out of that! When Armstrong was finally popped in 2012, they were willing to settle with him, and let him keep 5 of his TdF titles and take a temporary suspension that would mean he could still compete in the triathlons he’d been doing since he retired from cycling. He didn’t take that deal, because he’s an “all or nothing” kind of guy, but it seems pretty reasonable. Give everyone a second and third chance, not just the top-tier goliaths like Armstrong.

And for all the fans and amateurs out there - be realistic.

Everyone at the top dopes. Pillorying or excommunicating top level athletes for “doping” isn’t about cheating or enforcing fair and balanced standards, it’s arbitrarily destroying athlete’s careers and lives for having a bit of bad luck, because every other athlete you see on a TV screen is doping too, and they have to do that just to stay in the same relative place in the competitive landscape.

In his tell-all book, Jose Canseco estimated more than 60% of MLB players use PED’s, mostly gear and HGH.

“How do I know that? I was known as the godfather of steroids in baseball. I introduced steroids into the big leagues back in 1985, and taught other players how to use steroids and growth hormone. Back then, weight lifting was taboo in baseball. The teams didn't have weight-lifting programs. Teams didn't allow it. But once they saw what I could do as a result of my weight lifting, they said, "My God, if it's working for Jose, it's gotta work for a lot of players.”

Which was whistleblown by Grigory Rodchenkov, who fled and defected to America after two other top-level RUSADA officials “died unexpectedly,” then outlined the Russian doping program’s particulars to the US authorities and the New York Times, inspired the Mclaren investigation and report, and eventually inspired the 2017 movie Icarus.

Rodchenkov is currently in witness protection in the US, probably fearing a polonium tea service.

And don’t think it’s just Russia.

“At the 1972 Munich Olympics, U.S. track and field team member Jay Sylvester polled his male teammates about their drug use at the Games. His informal survey found that 68 percent of the American team was using anabolic steroids.”

From Mark Johnson’s Spitting in the Soup; inside the dirty game of doping in sports:

“With big money and enormous fan interest at stake, professional cycling needed to deliver spectacle, drama, and heroic suffering. Riders took drugs to help make that happen. On December 16, 1900, the New York Times described a high number of injured riders dropping out of a Madison Square Garden six-day race. Even after competitors “had been liberally dosed with stimulating drugs,” the Times reported, the infernal pace of racing and crash-sustained injuries were too much. Rather than helping riders gain an advantage over their competitors, drugs dispensed during turn-of-the-20th-century bike races were described as aids meant to merely keep the riders upright during grueling multiday events.”

The 1904 Olympics Marathon winner was a shambling corpse openly powered by strychnine and brandy, and there was a hue and cry as another competitor named Fred Lorz tried to claim the win after hitching part of the way to the finish line in a car. Hicks’ coach Lucas excoriated Lorz, “writing that he had nearly robbed Hicks, a newly crowned hero who was only “kept in mechanical action by the use of drugs, that he might bring to America the Marathon honors, which American athletes had failed to win both at Athens and at Paris.”

“Sixty-five years later, scientists still praised the use of performance-enhancing drugs in sports. In 1941, Springfield College professor, exercise physiologist, and sports science researcher Peter Karpovich defined the prevailing non-judgmental attitudes toward performance-enhancing drugs. In his “Ergogenic Aids in Work and Sport,” Karpovich rounded up current research on the physiological effects of substances, including alcohol, cocaine, amphetamines, hormones, pure oxygen, fruit juices, and sugar. Published in the Research Quarterly of the American Association for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, Karpovich’s study urged readers to avoid the term “doping” when referring to performance-enhancing drugs and athletes.”

“At a subsequent 1963 meeting on doping in sports, Dr. Antonio Venerando, president of the Italian Federation of Sports Medicine, observed that as of late 1963, international sports federations had only paid attention to doping cases in exceptional instances, and then only “for the sake of publicity rather than with any intention of getting to the root of the evil.” As described in a 1964 Council of Europe (CoE) report on these working meetings, he added, “In some countries doping is undertaken almost officially with a view to ensuring brilliant performances and the establishment of records which can be exploited in the field of international politics regardless of the consequences to the individual athlete.”

Not just that, when Armstrong was popped for cortisone in 1999:

“De Vriese also told Kathy he had learned that Armstrong arranged for $500,000 to be wired to the UCI after his positive corticosteroid test in 1999. The money, he believed, came from either Thom Weisel or Nike.”

Thom Weisel, the alpha male finance / IPO magnate and Postal team owner who put American cycling on the map, also had the head of the UCI, Hein Verbruggen, more or less bought:

“Through his control of the sport in the United States, and his ability to use his investment bank’s resources in the cycling world, Weisel also gained some influence over the UCI, which controlled the business and, significantly, all drug testing during the Tour de France. Ochowicz, in his role as head of the US governing body, made trips to Aigle, Switzerland, to meet with UCI president Hein Verbruggen. Ostensibly, he made the visits for the purpose of coordinating promotion of the sport and for reviewing details of upcoming Olympic events. But Ochowicz had another reason to visit: He often discussed financial transactions in Verbruggen’s brokerage account. Weisel, the hottest investment banker in Silicon Valley at the time, didn’t accept investments from just anybody. USADA and others believe the financial relationship represented a massive conflict of interest for Verbruggen. Armstrong was the sport’s biggest star, and Verbruggen, as head of the governing body, was his head disciplinarian. Had the USPS team wanted to transfer funds to Verbruggen, it would have been easy for Thomas Weisel Partners to let Verbruggen in on a hot IPO, which could have been worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not millions, depending on the “amount of Verbruggen’s investment. Weisel had helped other high-profile people in the cycling industry—including LeMond—in this way.

Verbruggen now had several disincentives to police Armstrong’s doping, and Armstrong would be thankful for them at various times throughout the remaining years of his career.”

“Expensive as these deals were, the sponsors felt they got their money’s worth. The Postal Service’s senior vice president Gail Sonnenberg estimated that it had gotten “millions and millions” of dollars’ worth of new business specifically because of its association with Armstrong and sponsorship of his team. In retrospect, the Postal Service’s decision in 1996 to put its brand on the start-up US cycling team appeared remarkably prescient—and cost-effective.”

“Armstrong’s victory also had a big impact on Wisconsin-based bike maker Trek. Soon it became widely known as the builder of the bikes on which Lance rode to his Tour victories. Sales of Trek’s most expensive bicycle line—bikes that sold for up to $4,000 each—more than doubled from 1998 to 1999; its total sales of road bikes rose 143 percent from 2000 to 2005.

Even Lance’s face on a Wheaties box pushed product. Boxes with Armstrong’s image sold about 10 percent better than other Wheaties boxes.

Overall, the “Lance effect” was profound. Between the time he began winning the Tour de France and his retirement, companies that made everything from bikes to helmets, cycling shoes to pedals, saw tremendous growth.

And no wonder! “He’s the all-American, Norman Rockwell–like embodiment of what people want their heroes to be,” marketing expert David Carter proclaimed in May 2000.”

Armstrong even considered buying the entire Tour de France, for around $1.5B, around 2010 / 2011, and thought it was a great business prospect but ultimately couldn’t arrange a deal that everyone was happy with.

The 1982 dip was driven by Hinault, the dominant cyclist by far at the time, sitting the tour out, with bad weather (lots of rain and cold temperatures) and TdF course changes featuring steeper and more difficult climbs also contributing, such that even when Hinault came back in ‘84, average speed still took a while to come back up.

To give you an idea of the level of motivation in most testing agencies - from roughly 1999 to 2010, USADA found only a couple hundred positive doping samples in tens of thousands tested. The first “name” athlete they popped was Floyd Landis, who was a TdF overall winner, vs Tyler Hamilton as just a stage winner and just-off-podium finisher.

“Since its inception, USADA had found only 209 possible violations in about forty thousand tests. Of those, 20 percent were dismissed after further review. Most of the violations the agency found were minor infractions involving little-known athletes, and there were complaints that the agency wasn’t effective at catching the real cheaters. But with its judgment against Landis, the agency seemed to be fulfilling its mission.”

Funnily enough, much like Hamilton, Landis was popped on something he probably wasn’t even doing - they got him for testosterone, and even after he came clean and admitted to doping and gave a ton of evidence a few years later, he still maintained he wasn’t doing testosterone at all in the window he got popped in. The rider number on the hot sample had been crossed out and his rider number written in by hand - his legal team actually showed persuasively that there were serious irregularities in the testing of that sample. But it was all for nothing, he’d gone for making the hearings public, and some of his friends had gone for Armstrong-like intimidation tactics, and that came out in the hearings and nuked him.

Also, the evidentiary standard for determining doping isn’t “a jury of your peers decides whether it’s beyond a reasonable doubt based on the evidence,” the procedure is “USADA or UCI chooses 3 judges, and if 2/3 are convinced that there’s a reasonable chance you doped, you doped.”

The GDR labs studied athlete responses to drugs at scale—known euphemistically in the GDR as “supplemental means.”

“East Germany’s Research Institute for Physical Culture and Sport had a staff of 600 full-time researchers dedicated to furthering elite-level East German athletic output, and the total number of GDR sports science researchers was estimated to be 1,500. About 1,000 doctors coordinated with 4,700 coaches while 5,000 volunteers and administrators kept the infrastructure humming along. Meanwhile, 3,000 Stasi agents ensured that anyone who questioned the logic or safety of this system did not enjoy its perks for long. Historian John Hoberman describes this system as the first-ever “Communist-style mobilization of thousands of people for the purpose of producing elite athletes.”

And they weren’t just pumping drugs into their athletes - they basically invented 80/20 polarized training, periodization and tapering of training intensities, and systematic HIIT, at a time when the training methods for most other countries at the time was “run as fast as you can for as at least 50 miles a week.”

In a medals-per-capita measure, Russia in 2014 is ~2x better than the USA, about in line with France and Germany, 3-5x surpassed by Belarus, Canada, Switzerland, and the Netherlands, and more than 10x below Austria and Norway.

Hot samples covered more than 1,000 athletes across 30 sports, so it’s not like it’s just weightlifting, you can see the full list of sports here: https://imgur.com/a/qDkZZQz

Landis, a big ex-Mennonite kid who was told he’d go to hell if he kept cycling, and chose to leave the Mennonites and keep cycling anyways and reached the top of the sport, was Hamilton’s replacement on Team Postal after Armstrong banished Hamilton from the inner circle.

Even Tyler Hamilton getting popped in 2004 was a farce - he was popped for “blood from other people being detected in his blood,” but he literally never intentionally did this, the only transfusions he ever did were self-tranfusions. The best explanation is that his doping doctor’s assistant inadvertently mixed up one of his bags with somebody else, or unintentionally contaminated his blood with somebody else’s when doing the blood freezing procedure that allowed the transfusion bags to have a longer shelf life.

If you carry two copies of UGT2B17, your T/E ratios also won't move even if doping, by enhancing your endogenous metabolization of testosterone. About 7% of Europeans and 1% of East Asians have a double copy.

For a fun example of how impossibly differentiated those mental schemas are in elite athletes, read here.

As just one example: From Muniz-Pumares, The Training Intensity Distribution of Marathon Runners Across Performance Levels (2024):

Elite marathoners (those turning in 2-2.5 hour times) run more than 3x the distance as more average marathoners.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-024-02137-7#citeas

It’s not just marathoners, of course - if you read books by or featuring elite athletes, they train constantly, generally 30-40 hours a week, across practically every sport.

Obviously he had the Livestrong Foundation, which raised many hundreds of millions directly (at least $500M). But more importantly, he was friends with top-level celebrities and politicians (including President Bush), and by campaigning for more cancer research there, he raised billions just in Texas.

“Over the years, Armstrong had indeed devoted considerable time and effort to the fight against cancer—not just on behalf of his foundation but as a political issue. As an icon in the cancer community, he had met with lawmakers, including Senator John Kerry, to lobby for more funding for cancer research, courted presidential candidates such as Democrat Barack Obama and Republican John McCain to push for more research dollars, and spoken at numerous fund-raisers around the country. His passionate testimony before Texas officials helped convince the legislature to pass a $3 billion cancer research referendum. He could rally millions of his “Livestrong Army” fans through his website to support cancer causes.”

If you can't get rid of doping (because it's too hard to catch) but you can't allow it either (because unrestricted doping is too dangerous), perhaps you can regulate in ways similar to how sports equipment is regulated? Explicitly allow doping methods that meet a given standard of safety, and ask all the athletes participating in the league to submit their proposed doping regimen for pre-approval. If - and this is a big if - the allowed doping methods are good enough that athletes *can't* easily do better by using methods that the league won't approve (because they're too dangerous), then you've removed most of the incentive to take especially dangerous risks.

Steroids got invented in 1958 and it took over 15 years for them to become staples in baseball? Holy crap.