A comprehensive guide to hypertrophy

377 pages of Renaissance Periodization condensed and summarized

Renaissance Periodization's Scientific Principles of Hypertrophy is a pinnacle achievement, one of those magnum opuses that stands apart in depth, rigor, and breadth, unchallenged on a mountain peak of sweet gains, surrounded by tiny yappy foothills of influencers and youtube stars and also-rans with their own slapdash, misinformed, and scarcely researched hypertrophy advice.

Before you even read the book RP recommends that you read three other books as a prerequisite, including Greg Nuckol's Art and Science of Lifting, a two book set (The Muscle and Strength Pyramids, by Dr. Eric Helms), and 300+ page textbook with more than 1,000 references (The Science and Development of Muscle Hypertrophy, by Dr. Brad Schoenfield), because “this is an advanced book” and you’ll need the grounding those other ones give you to really benefit from RP’s book here.

In this one they have the usual RP Phd-holding crew as authors, and also have Jared Feather as co-author, an IFBB pro with a masters in Exercise Physiology, who is also the head of bodybuilding contest prep at RP, and so has coached hundreds of men and women to placing in those. Each chapter in the book has 7-50 references.

I’m just trying to show you the level of detail and rigor they’ve brought to this before we get into it, because I’m necessarily going to be leaving a LOT out of their 377 pages here, but if you know the full picture is that well-backed, you’ll know if you want to get the book and read it yourself.

As always, Renaissance Periodization is on the efficient frontier of “scientifically rigorous” and “empirically verified” techniques and advice, thanks to their Phd backgrounds and epistemic review and incorporation of new studies, and thanks to the fact that they test everything via actual coaching towards competitive results.

So let’s begin.

They open with talking about specificity - basically, if you want to get swole, you need to focus on and primarily do things that are aligned with that. They give a helpful list of things that are NOT in line with this - the following are in LEAST-in-line with hypertrophy to most-in-line order:

Endurance Sports (Triathlon, Distance Swimming, Distance Running, Distance Cycling, etc.)

Combat Sports (MMA, Boxing, BJJ, etc.)

Team Sports (Soccer, Basketball, Volleyball, etc.)

Glycolytic Sports (Track Cycling, 400m/800m Running, 200m Swimming, etc.)

Gymnastic Sports (Gymnastics, Parkour, etc.)

Strength Sports (Strongman, Powerlifting, etc.)

Power Sports (Weightlifting, High Jump, etc.)

Technique-Based Sports (Table Tennis, Golf, etc.)

Low Impact Hobbies (Light Day Hiking, Frisbee, Yoga, etc.)

In other words, if you’re serious about something, don’t be expending a lot of your energy and bandwidth on stuff opposed to it. All the stuff at the top interfere because they fatigue you, demand incremental calories and recovery themselves, and do so in a way that directly interferes with muscle gain.

The second important point they make is that you need to have a plan, as in a specific idea of which muscles you want to get bigger. “All of them” is a popular answer, but if you’re anything but a newbie, you can’t do that. If you’re intermediate or above, the amount of time and stimulus needed to make muscles grow is too much to do “all of them,” so you need to focus on some subset.

Create an ordered priority ranking for body parts; muscles that are ranked higher on this priority list should usually be trained closer to the beginning of a training session, be trained with higher total volume per week, and with more isolation exercises, among other differences to be extensively explained in the chapter on the Overload principle.

The third important point? If you’re intermediate or advanced, you have to reliably eat at a surplus to gain muscle. That means you need to know your TDEE, and you need to eat above it to add muscle, so you need to be tracking your calories. Here I’ll just put in a plug for meal prep too - meal prepping your week’s food at the beginning of the week is the best way to make sure you’re hitting your calories and macros throughout the week, and it saves soooo much time, and makes life way easier.

I’ve personally always been at the high end of calorie needs (then again, I’ve been officially “overweight with abs” for nearly a decade now), so if you want some pointers on high calorie, easy meals, I’ve published some here.

How do you get big?

In a word, progressive overload. You’ve got to lift enough to give your muscles a stimulus you need to adapt to, and that stimulus needs to go up over time.

In order of importance, the things you need to be looking for in your workouts regarding stimulation:

Tension - “Muscle cells have tension receptors—molecular machines that detect and measure force passing through the tissue. To the extent that they detect force, these receptors initiate downstream molecular cascades that activate muscle growth machinery. The more tension detected, the more muscle growth is stimulated, across a large range of force values.” You need to lift heavy enough to stimulate those tension receptors, but not maximally heavy, because that will fatigue you too much to maintain ideal hypertrophy volumes. This is why hypertrophy “percent of max” typically range from 60-85% (although RP takes this down to 30-85%, and focuses on “reps in reserve”).

Volume - weight x sets x reps. In the average intermediate lifter this is between 2 and 15 sets per muscle group per session, and between 2 and 4 sessions a week.1

Relative effort - how hard your last set or your overall workout feels.

Range of Motion (ROM) - partial or full ROM - full is always better because different muscle receptors get triggered by different parts of the ROM, and generally the more the better.

Metabolite Accumulation - Muscle growth is probably triggered in proportion to both the amount of metabolites present and the duration of their presence.

Cell Swelling - the “pump” is itself a sign of the right amounts of stimulus and presages hypertrophy to come.

Mind-Muscle Connection - having a good enough mental model of your body and muscles that you can reliably tell when they’re exhausted or stimulated enough.

Movement Velocity - Both concentric and eccentric parts of the movement should always be controlled. Controlled explosive movements is better for fast twitch fibers, slower is better for slow twitch. The vast majority of hyptertrophy comes from fast twitch fibers.

Muscle Damage - the correlational relationship between how much damage is done and how much growth is achieved seems to be an inverted U-curve - recovery and adaptation compete with each other to some extent because they dip into the same finite pool of resources. If training is so damaging that recovery consumes nearly all resources, no actual adaptation (muscle growth) can occur!

How to use this in terms of gauging whether your workouts are effective?

Because the vast majority of hypertrophy stems from fast twitch fibers, you basically want to get close, but not too close, to failure. Getting too close means you’re spending more resources on recovery and fatiguing yourself more than is optimal. Staying too far away means you’re not pushing yourself hard enough to really engage the fast twitch fibers that drive most hypertrophy. The sweet spot is ~2-3 reps in reserve.

To clarify, “reps in reserve” is “how many reps you could have still successfully completed before failure.” To know this you need to have some experience, and you need to be dialed into your mind-muscle connection. You also need to have actually gone to failure multiple times.

If this isn’t something you think you have a good read on, I recommend you choose a comparatively easy weight and spend a week going to failure on as many lifts as you can, to actually dial this in. Take note of how you felt at 8 reps before failure, 7, 6,5,4,3,2, all the way to the last rep before you failed. Pay particular attention to how you felt in reps 5-0. This is your gauge, this is your “reps in reserve.”

I also recommend occasionally pushing to failure in a low-stakes set every once in a while across various muscle group exercises, just to make sure you stay well calibrated.

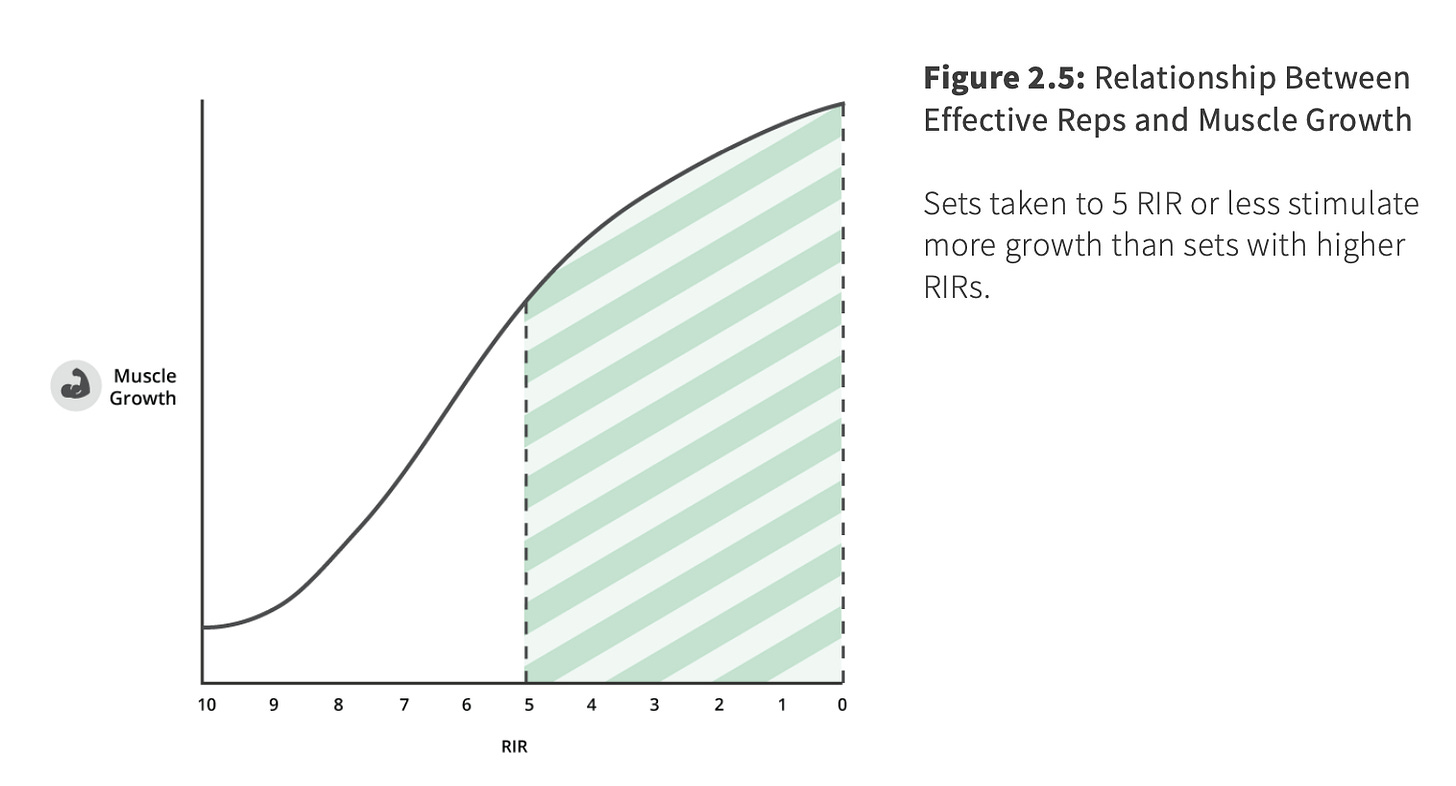

“As a set approaches muscular failure, faster twitch, larger, and more growth-prone motor units begin to activate more and generate a larger fraction of the total tension. The last five or so reps of a set taken close to failure sees the vast majority of the tension produced by the biggest and most growth-prone motor units. This activation occurs in the last five reps approaching failure no matter the load within the stimulus range. In other words, the last five reps of a 30 rep set to failure might require almost as much activation as the last five in a five rep set taken to failure. Because of this disproportionate contribution to the growth stimulus, reps of 5 RIR and lower have been termed “effective reps.”

Sets and reps

If you’re interested in hypertrophy, multiple sets matters, not just the total reps. Yes, it’s an S curve, where each incremental set drives less benefit overall, but empirical research shows that you need to get partway up that curve. Generally, the more your “hard sets” (5-0 RIR), the more your hypertrophy.

By counting the number of sets done at 5 or less RIR, we get a more accurate proxy for growth stimulus than we would by counting only effective reps.

The overwhelming direct research shows however, that two sets of 2-3 RIR actually confer about twice as much growth as one set taken to failure! This is probably because the other reps in a set do contribute to growth, even if less so.

How many sets is enough in a given workout? Probably 10-15 for a given muscle group,2 but it depends on your own level of development, the movement, and the weight. You don’t want to go much above 30 sets total, across all muscle groups, in a given workout, because anything above that are likely to be “junk reps” that add more fatigues than they’re worth. Note, this has the immediate implication that you can only train 2-3 muscle groups per workout, and since you need to train each muscle group between 2-4 times a week, that means only 2-6 muscle groups total are available for training per week.

Basically, you want to end up close to MAV, or maximum adaptive volume, where you’re stimulated to the maximum degree, but not so fatigued it’s going to interfere with recovery and future workouts.

How to determine MAV? It’s a very individual thing, and also a very noisy thing, that depends on lots of factors (your training level, your stress, whether you’ve been sick or not, how you’re eating, etc), so it’s something you need to dial in over many training sessions to extract the signal from the noise, and map out with your mind-muscle connection over time and many training sessions.

MAV Checklist:

If you are recovering ahead of schedule, add sets

If you are recovering from soreness just on time or even a bit late but still meeting performance targets, don’t add sets

If you’re under-recovering and failing to meet performance targets, you need to employ fatigue management strategies (covered in the next chapter)

Rep range

Your rep range should be between 10-20 for hypertrophy - much lower than 10, and you’re probably running too heavy, and much higher than 20 means you’re probably too light.

Velocity

Your velocity should be slower on eccentric and faster on concentric:

From a strictly theoretical perspective, larger forces are probably achieved with the following: a 2-3 second eccentric phase, a controlled “touch and go” amortization phase, and a relatively quick (but controlled) concentric phase.

For the time being and until much more research on the topic becomes available, if you’re in control of the weights and you’re not taking more than three seconds on any of the concentric, pause, or eccentric phase, you’re probably getting maximum or near-maximum effect.

Rest between sets

You need to rest enough to recharge your target muscles, your ancillary muscles, your nerves, and your breathing. For most sets, that’s 30s-4min.

Checklist on whether you’re recovered:

Are my target muscles still burning from the last set?

Are my ancillary muscles ready to go?

Do I feel mentally and physically like I can push hard with my chest again?

Is my breathing more or less back to normal?

Set variations

They actually don’t have my favorite set variation - pyramids, but they do have a few other ones.

For pyramids, which I like for accessories like bicep or triceps or flies, you choose a weight that’s probably 30-50% of your max, then you do a pyramid of between 5-8 sets up and down, with only a 1 second pause between each set (6 sets shown here, for a 36 rep pyramid) - 1 rep, pause, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.

You really feel the burn, and it’s a great finisher after your workout is mostly complete.

Progressive Overload

Is the key to all progress. As you get bigger and stronger, you need more stimulus to keep progressing. You need to increase sets or reps or weight. By keeping the 2-3 reps in reserve heuristic in mind, you should naturally tune this.

Your workouts should be:

Sufficiently close to the body’s peak output to be stimulative of adaptations

Increasingly challenging over time to keep driving adaptations

Remember this guy? You need to make sure you’re doing enough volume to be well past MEV. To keep loads heavy enough, as a hueristic, you should be adding at least a little bit of weight to the bar nearly every week.

In general for hypertrophy it is better to add sets - if you can’t add sets, then you add weight or reps.

But it’s a balancing act, which we’ll look at in a bit.

Mesocycles

Mesocycles are several-week training blocks, typically 1.5 - 2 months. You do “accumulation,” or increasing weight and volume for 4-6 weeks,3 then take a deload week.

“Microcycles” are a given training week in your mesocycle.

How you want to handle these for hypertrophy is to take your RIR from 5-4 at the beginning of your mesocycle, and be at 1-0 in the last week before deloading.

If you don’t want to mess with altering RIRs over the course of a mesocycle, shooting for around 2 RIR on all sets should get you very close to the best results. Even lifters who choose to stay at 2 RIR the whole time might consider going to 1 or 0 RIR in the last week before deloading, since the extra time to recover may justify the larger raw stimulus magnitudes of the lowest RIR training.

Sensitivity to volume usually adapts faster than our strength and RIR capabilities. This means a lot of people can benefit from both load and set progressions week to week. So not only should you add a little weight each week, if you can, you should add sets.

That means in terms of programming, you don’t want to start out super aggressive on sets and weight - you want to start out a little past your MEV (minimum effective volume), and keep adding sets / weight each week until you hit your MRV (maximum recoverable volume).

For an idea of the intensity of MEV, MAV, and MRV, here’s a useful graph:

A very important recommendation is to almost always err on the lighter side of

load progression. If you under-add weight, you can almost always make up for it

by making other exercises heavier or progressing faster in later weeks. But if you over-add weight, you might accumulate so much fatigue that you have to cut your progression short or take a series of unplanned recovery sessions, limiting your total gains for the mesocycle.

Common Hypertrophy Workout Mistakes

Not taking long enough rests - If you don’t rest long enough, you can be limited by being out of breath or some accessory muscles gassing versus your target muscles, and that limits the growth of your target muscles.

Junk volume - Junk volume is volume that adds fatigue but does not contribute to muscle growth. Junk volume usually comes from volume without sufficient specificity, tension, or relative effort. If you’re above 30 total sets across all muscles or movements in a single workout, you’re in junk volume territory.

Indexing too much on mind-muscle connection and how you feel - Don’t be this guy: “I don’t count reps or weight; I just go by feel and make sure the muscles are working.” Making sure the muscles are working is all well and good, but if you aren’t keeping track of load, volume, and relative effort your growth will be limited.

Ignoring exercise order - You’ve got to train your highest priority muscles first. If you’re working on your legs, squat before any other exercises. Similarly, lots of people want, say, rear delt development, but they have shoulder sessions that begin with presses, transition to side lateral raises, and end with rear delt work. How can you expect to grow your rear delts best if you always give them the short end of the stick?

Mistaking preference for stimulus - It’s like the man said: “Everyone wanna be big, but don’t nobody want to lift no heavy-ass weight!” Bench, squat, and deadlift are often one of the best lifts for hypertrophy, but also just plain difficult and tempting to skip. If you do include them, you might shirk on volume, and add more volume on easier lifts, but this is a mistake.

Not going hard enough - with specifics below.

Underdosing tension is usually done by those who prefer the drudgery of reps to the oppression of heavy weight, but it’s a balance, and you’re probably better off with some heavy weights closer to 85% in your training regime.

Underdosing volume is incredibly common. “As has been borne out by numerous recent studies, many people train with considerably less volume than they could benefit from, often by as much as a factor of three.” A lot of programs have you doing 5-15 working sets per muscle group per week (vs per session) - but there’s a decent chance you could be doing more and benefiting from it, especially if you’re intermediate or advanced.

Limiting ROM - Increases injury risk for little benefit. It’s better to do 2-3 biomechanically different exercises for the same muscle group.

Overindexing on one of sets, reps, or weight:

“You can only add so much of each stimulus week to week because recovery ability limits weekly progression. You might be able to add 5lb, 1 rep, and 1 set to an exercise each week; or 2.5lb, 2 reps, and 1 set; or 0lb, 2 reps, and 2 sets, etc. Each progression variable comes at the expense of the others. So, shouldn’t we just progress using the stimulus that has the greatest effect on muscle growth? The problem with this is that adding sets every week without adding reps or weight would eventually mean that the first few sets of a session would fall short of 0-5 RIR (as you became capable of more reps, but were not adding them in order to add sets). For example, if you start with one set of 10 at 3 RIR and next week add only another set of 10 at the same weight, that first set might now be 4 RIR because you’ve had a week to adapt to it. The second set might still be 3 RIR, but next week, the first set might be 5 RIR or higher. If you train like this for 4-6 weeks, many of your sets will simply be below the RIR hypertrophy range and growth will necessarily suffer.”

Going too hard

Thinking heavier is better - So yeah, don’t go over 85% - but also don’t stack up too much of your training close to 85%. This fatigues you more than it gives you gains, and takes away volume you could have spent better.

“when training within effective stimulus ranges for load and volume, so long as the RIR is equated, heavier training is theoretically no more beneficial than lighter training.”

Going beyond failure - ie having a spotter help you with the concentric portion, and doing a few more eccentrics. “People with limited time in the gym might consider going beyond failure, since fatigue accumulation is not a realistic concern for them, while efficiency is. Though even in these cases supersets and higher frequency training might be a better choice. Unfortunately, beyond-failure training in the real world is often used by those interested in max muscle growth and willing to spend hours in the gym, to their detriment.”

Fatigue Management and Recovery

If you’re working out hard enough, it’s going to fatigue you.

Fatigue is a necessary side effect of proper training and good growth won’t come without it.

Good program design first seeks the most muscle growth with the least fatigue possible and then aims to bring inevitable accumulating fatigue down occasionally to allow continued progress.

They had a pretty good kitchen analogy that I’ll include here:

For an analogy of fatigue management importance, imagine cooking delicious meals as akin to generating muscle growth. When a kitchen first opens, it is productive, the raw ingredients are plentiful, the counters, pans, and other tools are clean. At some point, “fatigue” starts to show. Pans and tools get dirty, some ingredients start to run out. You can still make decent food under such conditions, but it won’t be the best. Give the restaurant a few more days and no clean dishes or silverware will be left, nearly all food ingredient items will be gone or very low, and no more delicious meals can be made. Routine cleaning must be done to keep a kitchen clean and stocked and able to pump out delicious meals. Similarly, routine periods of fatigue alleviation must be used for any training program to continue to pump out good growth.

This is where recovery sessions and deload weeks come in.

Recovery in general is, without a doubt, the biggest and most important “frequently neglected” thing. Eating and sleeping well are BOTH just as important as lifting at your MAV, but they’re the first things people give up when under pressure (particularly sleep). But if you’re not eating and sleeping well, all that work in the gym was literally just wasted - it was a bunch of hard work and discipline, and it got you nothing.

So, pay attention to eating and sleeping. You should be eating above your TDEE for hypertrophy,4 and you should be getting a good 7-9 hours of high quality sleep at night.

For a more comprehensive look at recovery overall, I’ve reviewed RP’s book on Recovery here.

If you think you might be overtrained (which is fairly uncommon in hypertrophy mesocycles, and a lot more common in strength training or endurance training, but it can still happen), I’ve talked about gauging whether you’re overtrained, including some diagnostic tests you can do, here.

Two questions to ask when you’re working out in any given session, with an eye to the rest of the sessions in your mesocycle:

Is the current session stimulus enough to cause the best (or nearly the best) gains?

Is the current session stimulus so fatiguing that it will cut our planned progression short?

You want to be answering “Yes” to 1, and “No” to 2.

Question 1 is taking progressive overload into account, and question 2 is taking fatigue and recovery into account.

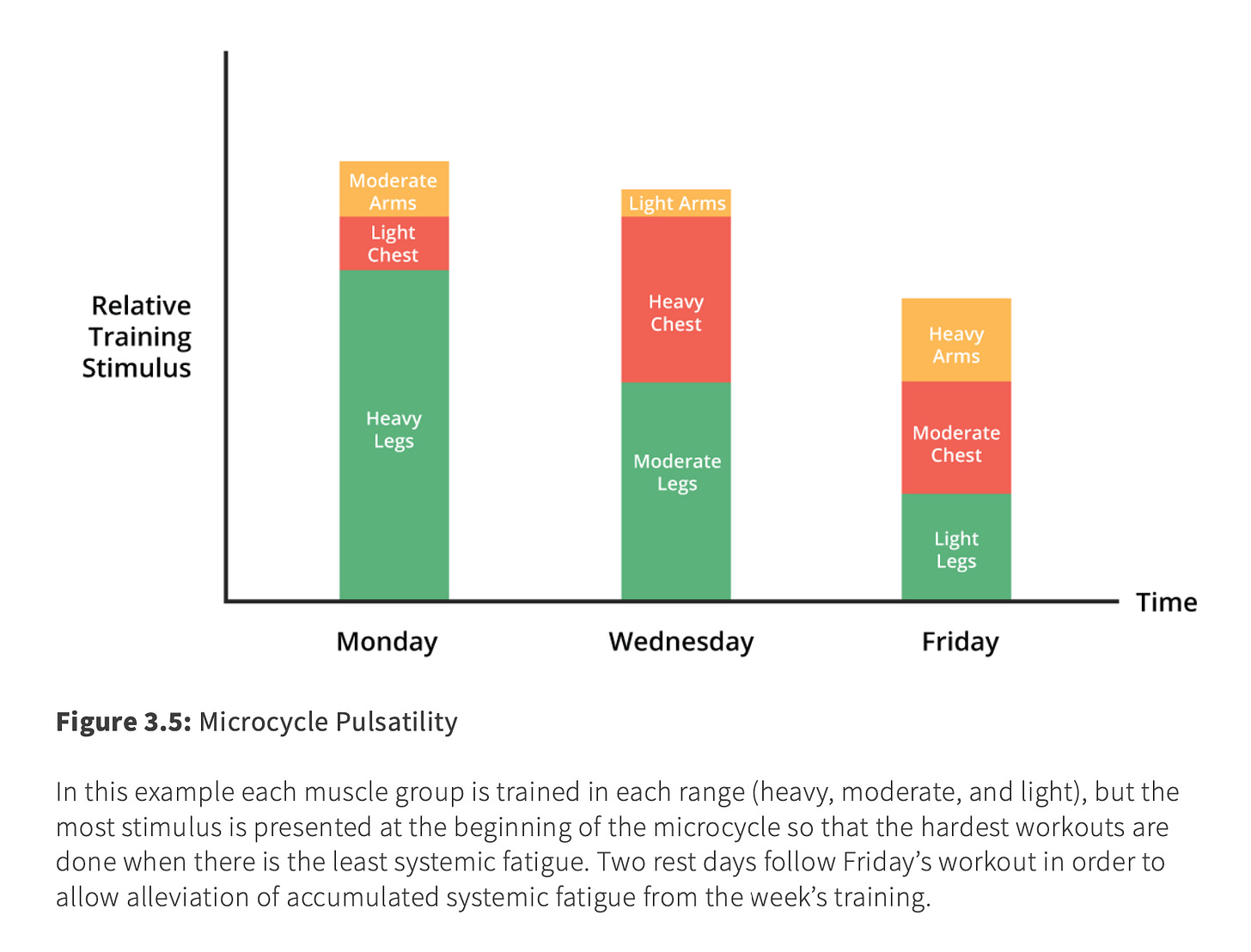

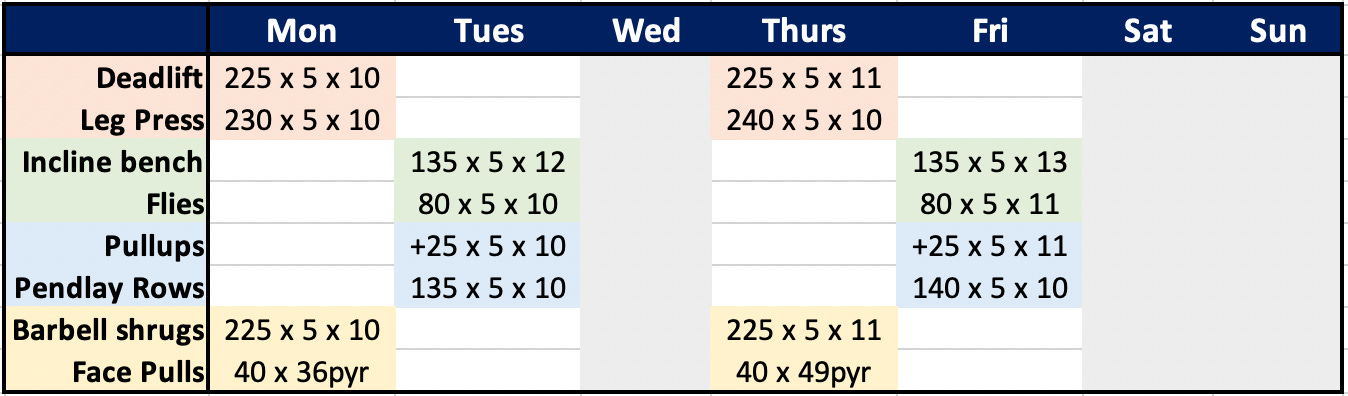

An example of how to stack the heavier and more fatiguing things earlier and the less fatiguing things at the end of the week:

When to do Recovery sessions or deloads

A recovery session is something you want to do if you’re feeling sick, have a twinge or pain that might presage injury, or if you’re really dragging and your bar velocity is low.

When you decide to do one, take your planned session and cut the working sets and the reps by half.

Example, instead of squatting 6x10 at 200lbs, you might squat 3x5 at 200lbs.

If for any reason you are not comfortable loading your planned weight for any reps, you can cut the load and sets in half and leave the reps as planned, which means in the above example you’d do 3x10 at 100lbs.

If it’s a particular muscle group giving you trouble, it’s better to do a recovery session just for those muscle group’s movements, rather than for everything.

When you hit MRV too early

You probably also want a recovery session if it looks like you will be over your MRV too soon in your mesocycle.

If you planned to match reps from the previous week with 2 RIR, but it took 1-0 RIR to match reps and you still have two weeks of accumulation, it might be time to take a recovery session for that muscle group.

On training when sick:

If you are sick and have systemic symptoms like a fever, you probably want to take as many days completely off as it takes to get better. If, on the other hand, you have just a minor cold without a fever, taking recovery sessions can actually speed recovery.

But you know, be considerate if you’re not using your home gym. Wear a mask, wipe down the equipment, and don’t infect other people.

Deloads

A deload week occurs at the end of your mesocycle, and is basically an entire week of recovery sessions. You should have pushed hard and progressed during your previous training weeks.

Deloads will often be needed when your RIRs approach 1 to 0 and are thus naturally placed at the end of accumulation phases when planned. Deloads should more often be a part of a pre-planned program, but sometimes need to be utilized in an autoreg- ulatory manner. An autoregulated deload is recommended when:

You have done recovery sessions and resumed training twice for more than half of your muscle groups in the current accumulation phase

More than half of your muscles have required a recovery session in the last two weeks (even if for the first time)

You have an illness with fever, or a serious injury that won’t heal in just a few days

These conditions indicate an elevation in both local and systemic fatigue.

Active Rest Periods

You typically do this once a year or so. Personally, I never do them intentionally (except when I was competing and specifically peaking before a meet), but have sometimes done them unintentionally over the years via hospitalizations or whatever.

It’s 1-4 weeks of rest. You can actually stop training entirely for 1-2 weeks without a ton of muscle loss, but if you’re going to go for 4 weeks, the last 2 weeks should be deload weeks.

Common recovery session or deload mistakes

Overindexing on “feeling good’ before training seriously again - Being fully recovered feels great, but if you’re sitting around feeling great all the time, you’re not adding muscle at the rate you could be (or at all, if you’re intermediate or advanced).

Overindexing on your “recovered” performance gains - A lot of times after a deload week, or even a week off, you’ll come back stronger than ever. You may then think, “hey, lifting light (or resting) and making sure I was fully recovered is hugely anabolic, I should do this all the time!” But what’s really happening is that fatigue masks performance, and you actually built that strength up in your working sessions, and just weren’t able to perform at that level in your last week because of fatigue. But if you decided to go light / deload more often, or take weeks off more often, you’re not going to make progress.

If you were not aware that fatigue masks adaptations, you might assume that because less volume or relative effort resulted in better performance, you were getting better gains with low volume, light lifting. Unfortunately, low volume, low load training does not lead to as much muscle gain.

Excessive fear of injury - This is one of those things where some people need to hear this and some people need to ignore it. Hopefully you know which one you are.

Not every pain sensation means injury. If you feel some tweaking or discomfort, ease in carefully, but see if it can be worked through. If pain fades as you carefully work through your warm-up, you’re probably fine. If the pain stays the same, consider switching techniques or exercises. If it increases as you work, a recovery session is likely in order. Be wary of injury, but avoid giving up a full training session every time you feel any discomfort.

Overindexing on how you feel - same thing, just with soreness, motivation, bar velocity, how heavy it feels, etc. Those things can happen and not indicate overtraining or a need for a recovery session or premature deload week. Take perceptual measures of fatigue with a grain of salt, in other words.

Going too hard - it’s tempting when you’re fresh off a deload week and feeling great, your bar velocity is smooth and fast, and you see that your program is calling for 10-12 sets for this muscle in the first week, to do 15-16 sets instead. But we’re not optimizing “pushing ourselves,” although a lot of time it looks and feels that way - we’re optimizing muscle growth, and less challenging workouts in the beginning of a mesocycle allow for more weeks of progression and accumulated load.

it can be psychologically tough to apply small, incremental stimuli over time. It’s hard to add just one set if you feel like you can add three sets, or 5lb if you feel like you can add 15lb. But rushing the process will prevent your best gains.

Program heuristics

Alright, so we’ve been throwing optimal hypertrophy concepts at you left and right, but how do we take all this and design a solid training program?

First, figure out your priorities

It’s easy to say you want to improve ALL your muscles, but this is unrealistic if you’re intermediate or advanced.

The reason behind this is “junk volume.” Biceps, triceps, calves, hams, quads, glutes, back and shoulders is 8 muscle groups. You shouldn’t do more than 30 sets total, across all muscle groups, per session, because anything above that is usually junk volume, ie it’s more systemically fatiguing than it’s worth. Even if you train each muscle group only 2x per week, and only 10 sets each, that’s 160 sets a week. If you divide 160 by the 30 total sets cap, that’s working out 5x a week.

Worse, if you’re intermediate or advanced, your per-session total cap is probably closer to 20-25 sets, AND you usually have to work out harder and with more sets to progress, AND you usually have more esoteric muscle goals, like forearms, traps, or upper / lower pecs or upper / lower back.

The point is, you need to prioritize. You’re going to be better off narrowing your focus on a given mesocycle to 1-4 muscle groups, and aiming at the lower end of that if you’re intermediate or advanced.

A realistic intermediate training week:

So if we’re going to do 4 training sessions a week, and 2 training sets per muscle group per week, and 10-15 sets per muscle group, you can only do ~2 muscle groups per day, and ~4 muscle groups total in this mesocycle.

Remember, a mesocycle should be 4-6 weeks of accumulation, then a deload week. You can switch out muscle groups in your next mesocycle if you’re happy with your progress. Sometimes, depending on your development and individual muscles and how advanced you are, you’ll need to keep some muscle groups in your rotation at MEV (minimum effective volume) while going for MAV / MRV (maximum adaptive / recoverable volume) for other groups just to make sure you don’t lose muscle in the MEV group.

So you can map a microcycle (one week) out. Let’s say it was legs, chest, back, and biceps. It probably looks something like this towards the middle or end of your mesocycle:

Two rules for week-to-week progression:

If you are increasing weekly load (weight), add only enough to allow at least the same reps, at the same or slightly lower RIR.

If you are increasing weekly reps, add only enough to allow at least the same load, at the same or slightly lower RIR. In either case, shoot for at least four weeks of accumulation in your mesocycle.

One rule for Mesocycle to Mesocycle progression:

A training block presumably starts out with low fatigue, faster twitch characteristics on average, and a lower MEV. Thus heavier, lower frequency training is ideal at first. As mesocycles progress, fatigue accumulates, fibers convert slightly to slower twitch, and MEV rises, necessitating higher volumes and frequencies as well as lighter loads. And because higher frequencies are less sustainable, placing them only after lower frequency mesos have been completed leads to longer periods of productive training.

But let’s say you want to start from zero, build a microcycle, then a mesocycle

First, decide on the muscle groups you’re going to be targeting, per the advice above. Popular choices again are: Biceps, triceps, calves, hams, quads, glutes, back and shoulders.

Now, we need to know how to dial in our MEV - minimum effective volume, for a given target muscle group.

To do this, you’ll do a weight and number of sets and reps you think is close to your MEV, erring on the lower side. I’d personally recommend doing something like 60% of your max for 5 sets x 10 reps, or thereabouts, but if you have a different opinion, you know yourself better than I do.

Then ask yourself:

On a scale of 0-3, how much did this challenge your target muscles?

0: You felt barely aware of your target muscles during the exercise

1: You felt like your target muscles worked, but mildly

2: You felt a good amount of tension and or burn in the target muscles

3: You felt tension and burn close to the limit in your target muscles

On a scale of 0-3, how much pump did you experience in the target muscles?

0: You got no pump at all in the target muscles

1: You got a very mild pump in the target muscles

2: You got a decent pump in the target muscles

3: You got close to maximal pump in the target muscles

On a scale of 0-3, how much did the session disrupt your target muscles?

0: You had no fatigue, perturbation, or soreness in the target muscles

1: You had some weakness and stiffness after the session in the target muscles, but recovered by the next day

2: You had some weakness and stiffness in the target muscles after the session- and had some soreness the following day

3: You got much weaker and felt perturbation in the target muscles right after the session and also had soreness for a few days or more

Add up your total (0-9), then refer to this chart:

Do this till you’re dialed in on your MEV, for as many muscle groups as you’re going to be focusing on.

Now sketch out your preliminary program, with the MEV weight, sets, and reps for each muscle group, for the first week of your mesocycle. It’s going to look something like this:

You’re going to have your MEV there for each exercise / muscle group. But you’ve still got 3-5 more weeks after this in the accumulation part of your mesocycle before you do a deload week, and you’re going to have to be going up in weight, sets, and reps, ideally up to your MAV (maximum adaptive volume), and your MRV (maximum recoverable volume) on the last week or two.

Next you need a heuristic for whether to add sets or not:

You’ve dialed in your MEV, and now you need to decide how many sets to do. Adding sets is generally better than adding weight or reps for hypertrophy. You’re going to get a “soreness” score and a “performance” score:

On a scale of 0-3 how sore did you get in the target muscles?

0: You did not get at all sore in the target muscles

1: You got stiff for a few hours after training and had mild soreness in the target muscles that resolved by next session targeting the same muscles

2: You got DOMS in the target muscles that resolved just in time for the next session targeting the same muscles

3: You got DOMS in the target muscles that remained for the next session target- ing the same muscles

On a scale of 0-3 how was your performance?

0: You hit your target reps, but either had to do 2 more reps than planned to hit target RIR or you hit your target reps at 2 or more reps before target RIR

1: You hit your target reps, but either had to do 0-1 more reps than planned to hit target RIR or you hit your target reps at 1 rep before target RIR

2: You hit your target reps after your target RIR

3: You could not match last week’s reps at any RIR

Note that in the above description, “target reps” refer to the goal reps for that week.

If you are progressing via weight and you curled 60lb for 10,8,6 reps last week, your goal this week at 65lb should be 10,8,6 again. If you are progressing on reps the target reps might be 11,9,7 with 60lb.

Now refer to the table:

Note that no matter how little soreness you are experiencing, if you score a 2 or higher on (lack of) performance you should not add sets and if you score a 3, you should employ recovery strategies (to be discussed in the fatigue management chapter).

So for your next week in your mesocycle, you follow this algorithm to decide whether to add sets for a given exercise for your next microcycle / week. If you can’t add sets, you can try to add a small amount of weight or reps to keep progressive overload going.

Remember, the goal is to accumulate for the entire remaining weeks of your mesocycle, so slow and steady progression is the name of the game. You don’t want to go too hard and have to take recovery sessions or a premature deload week.

That’s really enough to put together your first mesocycle from the ground up.

Want another example? Here’s one I did recently, when building back up from a large weight and strength loss from triathlon training.

You start with your starting week (MEV in this case, but for the start of your next mesocycle, I generally start with week 4’s weight / reps / sets), then you add sets if you can, and if you can’t add sets, you add weight or reps, so that you’re progressing each week, up to week 5 or 6, after which you deload.

Examples

Example 1:

You train pecs with 4 sets of bench press in Session A on Monday.You got a good pump and a bit of soreness.

You wait for soreness to be completely gone and this takes one whole day,so you then train 4 sets of incline bench in Session B Wednesday.

Performance in Session B is at or above baseline,so you train with 4 sets of machine presses on Friday’s Session C as planned.

Next Monday, you increase your bench press volume to 5 sets in Session A2 so that you get a comparable pump to you first week’s Session A.

You heal on time to perform well on Wednesday’s Session B2, and you have derived that your working frequency for chest is at 3x a week. You continue to add sets as-needed through the accumulation phase, eventually topping out at eight sets per session on average for a total MRV of 24 sets per week for chest.

Example 2:

You train hamstrings on Monday’s Session A with 4 sets of lying leg curls.

Soreness heals in two days, by Wednesday, and you train Good-Mornings for 4

sets.

Performance in Wednesday’s session (Session B) is at or above baseline,so you

train with 4 sets of seated leg curls in Friday’s Session C. But you are still sore from Good Mornings and don’t perform as planned on seated leg curls. You rest until Monday and do Session A2.

You do 5 sets of lying leg curls on Mondays’ A2 because you didn’t get too pumped or sore from that session last time, calling for a volume raise accord- ing to the Set Progression Algorithm.

Since you now know that Good Mornings are very taxing even at their MEV, and that they require a longer SRA interval, instead of training them on Wednesday you move them to Thursday and do 2 sets of good mornings plus 2 sets of seated leg curls. You recover fully from soreness and perform well next Monday (Session A3), and you continue to add sets as needed through the accumulation phase with your newly derived frequency of 2x per week for hamstring training.

It is essential that you hit close to your MEV when you first execute this algorithm. It’s easy to train well above MEV, need more days to recover, and mistakenly derive a very low training frequency for all of your muscles—leading you to miss out on potential gains. At MEV, you know that the recovery time is solely determined by the intrinsic factors of that muscle and not by the excess volume. Training with less than MEV would also lead you to conclude that you can benefit from an ultra-high frequency—also leading you to miss out on potential gains by erroneously adopting an excessively frequent program.

Looking over all sessions, if soreness healed just on time for the next session on average, especially at higher (7+ sets) volumes, leave the training frequency where it is. If it healed a day or more before the next session, increase the frequency by one extra session in the next mesocycle. If at any given point overlapping soreness or perfor- mance loss are repeatedly occurring in the higher (7+) volumes, or the Set Progres- sion Algorithm prevented volume increases, consider removing a session in the next mesocycle.

Example 3:

You start by training your side delts 2x a week.

You work up to 12 sets per session of side delts before the end of the mesocycle.

You at most get sore for a day or so after, never longer.

You don’t ever experience performance loss in the side delt exercises, and are well-recovered for each successive session.

In your next mesocycle, you add a session to side delts, going from 2x per week

to 3x.

Example 4:

You start by training your quads 2x a week.

You work up to 12 sets per quad session before the end of the mesocycle.

You get very sore in the quads,but they almost always heal just in time for their next session of the week.

Your quad performance hangs in and improves a bit towards the very end of your mesocycle.

In your next mesocycle, you don’t change your frequency, and you stick with 2x per week for quads for the time being.

Example 5:

You start by training your hamstrings 3x aweek.

You work up to 8 sets of hamstrings per session before the end of the mesocycle.

You get debilitating soreness in your hamstrings that overlaps from one session to the next.

Your hamstring performance starts to decline, and you have to deload hamstring training earlier than planned.

In your next mesocycle, you switch down to 2x hamstring training per week, because 3 sessions were overkill and did not allow for sufficient recovery.

One last topic before we wrap up - Variation

The Principle of Variation of Training: To improve at a specific sport or physical endeavor, training must occasionally be varied to maintain effective stimulus and prevent wear and tear injury. This variation must occur within the bounds of the principle of Specificity.

Basically, you want to mix it up. I’m sure you’ve heard people enthusiastic about “muscle confusion.” Same basic concept, but RP are too classy and scientific to use the term.

The primary reason to mix things up, at least IMO, is to prevent injury, repetitive use, and wear and tear.

One example from my own life: I do Wim Hof breathing and breath-hold pushups every morning, and since pushups aren’t much of a stimulus, I kept cranking it up. I do between 100-150 during the breath hold, but then after that I would do another 100, or another 150. But after a few months of doing 300 pushups a morning, a tendon in my right arm that’s prone to overuse injury started flaring up, and affecting my swimming and lifting. I was fatiguing myself and wearing out my tendon for basically nothing, because pushups aren’t enough stimulus to actually make you stronger or add muscle (at least for myself), but it was enough to irritate my tendon and add to my systemic fatigue.

This is an example of doing too much of something that has gotten stale, and increasing injury risk. It’s also a good example of “junk volume.”

Similarly, if you get too comfortably in a rut, and ALL you do is flat bench, or low bar squats, or whatever, you’re going to increase the risk of injury, you’re going to get bored, and your muscles are going to stop responding as strongly. As RP puts it: “It seems that the human muscles and nervous system adapt and become less sensitive to any given stimulus over time.”

Hence, variation.

Front squat or high bar squat instead of low bar (or vice versa). Sumo deadlift instead of conventional. Incline bench vs flat. But even then there’s so much more - on the topic of bench, you can also use machines, dumbbells, do pause reps, explosive reps, and much more.

There’s also “directed variation,” or changing the focus of your programming to accommodate your priorities while maintaining your gains, which is something more advanced lifters often need to do:

An example of directed variation in the context of hypertrophy would be training legs at MEV while alternating mesos of MEV to MRV back and MEV to MRV chest training because the current priority is to bring up the upper body. Variation here is organized within the confines of a specific hypertrophy goal: upper body growth.

Three questions to ask to decide if you should adopt a variation:

Has performance stalled?

Is this exercise hurting me?

Is this exercise feeling stale?

Variation Examples

Compound vs. isolation

Unilateral vs. bilateral

Comparable exercises for an agonist muscle

Barbells vs. dumbbells vs. machines, vs. accommodating resistance (bands,

etc.)

Positioning of hands or feet

Movement Velocity

Cadence

Pause inclusion and duration

Concentric vs. eccentric emphasis

Mind-muscle connection vs. simple rep completion

Wrap up

They have a final chapter on phase potentiation and another on individualization with a lot of tips for advanced lifters, people in different stages of their diets, etc, but that’s really getting into the decimal places, and this is running long already.

But if you’re an advanced lifter, or were interested in more details or getting deeper, definitely get the book itself!

I hope this is helpful for anybody out there who wants to get serious about hypertrophy.

“When equated for volume, 3x a week training seems to be better than 2x a week training by a small but notable factor. 4x a week training is better than 3x by a much smaller factor, and 5x a week is better than 4x a week by an almost indistinguishable factor.”

“Per session MAVs are not likely to be more than 15 sets per muscle group in most of the groups studied and are probably somewhat more likely to be in the 5-10 set per session range. In terms of total session volume (including all muscle groups worked) 25 total sets per session is a likely average MRV cap. Some people can do north of 30 productive sets per session, but anything much more than 30 sets should raise a skeptical eyebrow.”

RP says:

Notice that there is no top end to accumulation length. In general, when the average lifter trains most of their body between MEV and MRV using the above stipulations, accumulations will likely hit MRV in six weeks or less, though beginners might be able to go as long as eight weeks or even longer. Anything much longer usually means understimulative training at the start, minimal RIR progression, a failure to add volume as performance increases (understimulative training across the meso), or some combination.

Eat above TDEE by how much? As a heuristic, you don’t want to bulk at much more than 0.5% of your body weight per week, as anything more than that and you’re likely to be adding more fat than muscle.

Basically, you should have your present weight, and a goal weight. The goal weight shouldn’t be any more than 10% higher, and your weekly surplus should be goal weight / 12 (to represent a 3 month / 2 mesocycle time interval), and shouldn’t be more than 0.5%.

Then multiply your current weight by your % per week - that’s the incremental lbs per week gain you’re shooting for. Now multiply that number by 3500. Mine looks like 0.83 lbs per week and tells me I need ~417 more calories per day across the week. BUT if you’re increasing your workout load on this hypertrophy journey, which you should be, and that isn’t reflected in your current TDEE, then you need to compensate for the additional energy you’re going to be burning in that incremental workload. For myself with 5 hypertrophy workouts a week and 2 rest days, that shakes out to 875 calories more per day on average.

I actually tune this by macros and light / moderate / heavy workout days, if you’re really interested in this, just DM me and I’ll share a spreadsheet with you that does all this.