Is an elite athlete more nature, or more nurture?

This should be fun - like most rational-adjacent folks, I’ve settled on a heuristic that’s roughly “pretty much anything we might care about is ~80/20 nature vs nurture.”

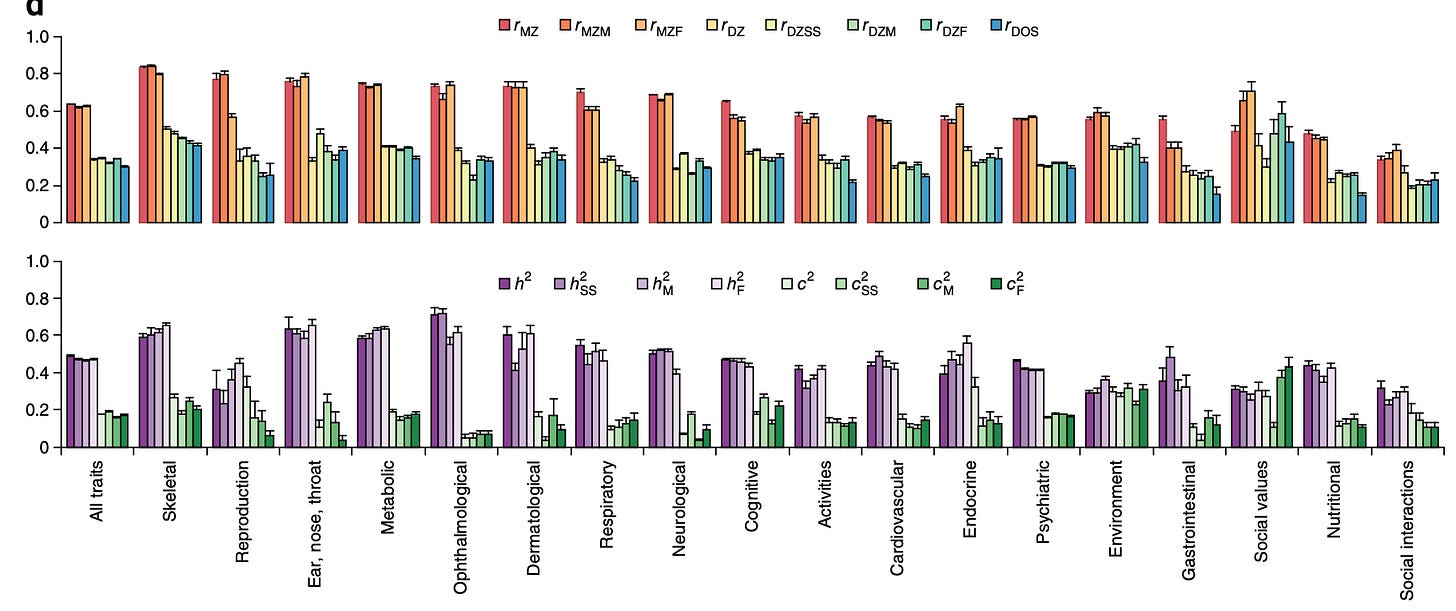

The classic cite I typically fall back on for that is Polderman 2015, the massive twin study meta-analysis that (IMO) put this question to rest nearly a decade ago1:

But on the other hand, we know that being competitive at the elite level in sport pretty much *requires* thousands of hours of skilled and deliberate practice. The quintessential “10,000 hours” road to skilled expertise.

And after all, the “10k hours” trope is sort of the ultimate “blank slate” Trojan Horse - if we’re to believe Malcolm Gladwell2 in Outliers, anyone who puts in their 10k hours is going to be an expert.

So? How true is that? Which effect wins?

Lol, cmon! Do you even have to ask?? Genetics ALWAYS wins these things!

But the story is a fun and fascinating one, so let’s look into it.

Let’s begin with the same story Epstein begins with, which I believe was originally a Sports Illustrated article that he expanded into the book.

This is a tale of two high jumpers, a tale of an ant and a grasshopper.

Our ant?

Stefan Holm is a Swedish high jumper, an Olympic gold medaler who cleared 7’ 9” while only 5’ 11” tall himself,3 who had literally been high jumping over couches since before Kindergarten, and who has been training in a professional-grade high jumping facility year round since the age of 11.

Holm is the epitome of the “well, I’ll work twice as hard then” work ethic. 5-6 inches shorter than an average high jumper, with a mediocre 28” vertical leap, Holm sprints at the bar at 19mph(!) to generate enough force to clear bars much taller than he is.

His jump improved a few centimeters nearly annually between 1987 and 2005. In 1998, he just missed the Olympic podium in Sydney, so he dropped out of college, moved right next to his training facility, and doubled down on training. He would do a minimum of 30 full competition-speed-and-effort high jumps every day, and it was a minimum because he would refuse to go home, nor lower the bar, until he made it over whatever height he was confronting in training. Between his training and competition schedules over 20 years, Holm thinks he’s probably taken more high jumps than any human being who has ever lived.

“When scientists examined Holm, they determined that his left Achilles tendon had hardened so much from his workout regimen that a force of 1.8 tons was needed to stretch it a single centimeter, about 4 times the stiffness of an average man’s Achilles”

So Holm *earned* his gold medal, the hard way, over decades.

Who is our grasshopper?

Donald Thomas, a high jumper from the Bahamas, who ended up competing against Holm in the 2007 World Championships in Osaka, Japan.

Thomas had never even trained the high jump. The first high jump he took was in 2006, and was a result of trash talk in his college cafeteria where he bragged about his dunking prowess and a high jumper bet him he couldn’t clear a 6’ 6” bar. That night, Thomas cleared a 7’ bar. The high jumper got on the phone with his coach, who got Thomas in as a last minute entry in a meet 2 days later. That day at the meet, Thomas not only qualified for the national championships, he set his college’s high jump record AND, on the 7th high jump of his life, broke the meet venue’s record, with by all accounts, rigid and terrible high jump form.

One of his cousins more or less immediately recruited him to a different college under a full scholarship. And once there, Thomas would routinely cut practice, go out for “a drink of water” and never come back, and refused to wear high jump shoes.

When Thomas and Holm faced off in the 2007 Championship in Osaka, Thomas had been high jumping for a total of 8 months. Holm missed on 7’ 8.5” (2.35m) three times, and Thomas made it on his first try, despite barely sprinting and slowing down greatly right before jumping.

The guy who wouldn’t even wear high jump shoes, who had been high jumping for less than a year, and who thought high jump was “kind of boring,” had won the 2007 World Championship. On his winning jump, Thomas had raised his center of mass to 8’ 2” - if he had had any semblance of proper form, he could have shattered the world record.

In the 17 years since he entered the professional high jumping circuit, Thomas hasn’t improved by a single centimeter - all of his competition jumps have been less than the 2.35m he jumped in 2007, with 8 months of half-hearted training. The highest he’s attained since then is 2.32m, and if you average all his jumps 2022-2024, they’re at around 2.22m. The worst part is, on his best day, Holm should have clobbered him - Holm jumped a 2.4m in 2005, but decided to retire the year after he lost to Thomas.

When scientists studied Thomas, they found out that he had a gigantic Achilles tendon, 10.25 inches, uncharacteristically long for his height (6’ 3”).

Donald Thomas is the anti-10k hours story.

But he’s not the only one.

Alisa Camplin had literally never even seen snow in 1994. As part of the Australian talent search for Olympic quality athletes, in 1994 she was persuaded to try aerial ski jumping.

On her first jump, she broke a rib. On her second, she hit a tree. She was 20 years old, a former gymnast who was 5’ 2” tall, and had literally never even seen snow, much less skiied. Her window for “early skill acquisition” was looooong gone. Nevertheless, by 1997 she was competing on the World Cup circuit. In 2002, she won Gold despite breaking *both* of her ankles 6 weeks earlier. Much like Donald Thomas, whose high jump form was notoriously bad, it was said that even after she had won gold, that watching Camplin on skis was “like watching a giraffe on roller skates.” She actually crushed her victory flowers because she fell while skiing down the mountain to the gold medal winner’s press conference.

Skeleton bobsled is another winter sport, kind of like luge, but for single racers. We have Australia to thank for this case study too - Aussie coaches had never even seen the sport, but they decided to go for it. Of the written applications, they chose 26 women and invited them to come to tryouts. Most of the applicants had never seen snow. Most of them were beach racers, competing in “surf lifesaving.”

Ten weeks after she first competed on ice, Melissa Hoar bested half the field at the World Skeleton Championships, and won the title on her next try. Beach sprinter Michelle Steele made it all the way to the Winter Olympics in Italy. Australian scientists wrote a paper smugly titled “Ice novice to Winter Olympian in 14 months.”

As you can probably infer, Australia takes athletic talent search much more seriously, and takes risks most other countries won’t take, which is why most of these fun “novices dominate everyone and go to the Olympics” stories are about Australian athletes. And it pays! In the Sydney Olympics, Australia won 3.03 medals for every million citizens, nearly 10x the US, which took home 0.33 medals per million Americans.4

Another fun factoid in this realm? The Belgian men’s field hockey team cumulatively average >10k hours of practice on average. This is thousands more than the Dutch team, but the Belgians have medaled in 2 Olympics since 1996, while the Dutch are a world powerhouse at field hockey, having medaled at 7 Olympics since 1996.

One final case study - the would-be PGA Pro, Dan Maclaughlin

Dan Maclaughlin was the darling of many books and magazines for a few years with his “Dan Plan,” because he retired from his job as a photographer at age 30, and set out with the deliberate goal to “put 10k hours of training in and become a PGA pro.”

Since the Dan Plan was a multi-year plan starting in 2011, all of the books and articles were only able to breathlessly burble about his progress so far and his overall confidence in the plan.

To his credit, he took it really seriously. He worked in an ongoing way with K Anders Ericsson to make sure he was only logging hours of “deliberate practice” rather than empty hours, and spent 4-6 hours a day on it for nearly 5 years.

“He got his handicap to only 5.2 in ~2 years!” The books would breathlessly relate.

So whatever happened with the Dan Plan, did Dan ever get his PGA card?

No!

He eventually got to around 6k hours in late 2015, and his peak handicap was 2.6. That’s a good handicap, but PGA Pros usually average around +4-6 handicap, with the plus meaning the other way past 0, so even at 2.6, Dan was 6-9 strokes off, which is a pretty significant gulf.

Given how strict he was about allocating only “deliberate practice” hours, he probably had 10k hours in the Gladwellian or layman sense. Broadly, he got to “top 5% of golf players,” when he needed to be at “top 0.1%” to average what a PGA card carrier averages.

Why did he give up? He cites a herniated disc and back pain, and eventually went back to commercial photography.

Unsurprisingly, innate talent is definitely a thing.

If you had to bet on “novice in this particular sport but an elite athlete otherwise” vs “sub-elite athlete with ten thousand hours of sport-specific training,” bet on the elite, full stop!

The fact that Australia is one of the only countries that routinely does this speaks more to most other country’s lack of will to rigorously talent search and win rather than any principled stance or empirical truth.

But we can’t just conclude this from a couple of case studies!

Have we no shame? In this era of Replication Crises?? So yeah, let’s look at some studies.

Enter the HERITAGE study about exercise response, which took 473 people, had them all follow the same exercise regime, and measured various physical stats and then did genome sequencing and analysis on each person.

“At each of the four centers where volunteers were made to exercise—Indiana University, University of Minnesota, Texas A&M, and Laval University in Quebec—the results of HERITAGE were astonishingly consistent. Despite the fact that every member of the study was on an identical exercise program, all four sites saw a vast and similar spectrum of aerobic capacity improvement, from about 15 percent of participants who showed little or no gain whatsoever after five months of training all the way up to the 15 percent of participants who improved dramatically, increasing the amount of oxygen their bodies could use by 50 percent or more.”

They identified 21 positively impacting gene variants that affected exercise response, and saw that study participants who had at least 19 of the genes had ~3x VO2max improvement versus people with fewer than 10 of the variants. (GWAS studies have since brought the number of genes like this into the hundreds).

David Wechsler (of IQ test fame) compiled all of the credible data he could find on human measurements in 1935, and found the range of “smallest to biggest” or “best to worst” in just about any measure is 2-3x for the top performers, with the bottom indexed at 1.

Philip Ackerman, a Georgia Tech psychologist and skill acquisition expert, has done similar anthropometric studies, and he finds that in simple tasks, practice makes people converge in terms of skill level, but that in complex ones, it pulls people apart. There is a “Matthew effect” on skill acquisition - the people who start the best typically learn and advance faster, too. Even among simple skills, practice makes people converge, but it never eliminates talent spreads - “there’s not a single study where visibility between subjects disappears entirely.”

“If you go to the grocery store,” he continues, “you can look at the checkout clerk, who is using mostly perceptual motor skill. On average, the people who’ve been doing it for ten years will get through ten customers in the time the new people get across one. But the fastest person with ten years’ experience will still be about three times faster than the slowest person with ten years’ experience.”

Wolfgang Schneider was enlisted by the German Tennis Federation to recruit 106 child tennis players and track their performance over time, to see if they could predict in childhood what factors make somebody an elite tennis player later in life.

“When the researchers eventually fit their data to the actual rankings of the players later on, the children’s tennis-specific skill scores predicted 60 to 70 percent of the variance in their eventual adult tennis ranking. But another finding surprised Schneider. The tests of general athleticism—for example, a thirty-meter sprint and start-and-stop agility drills—influenced which children would acquire the tennis-specific skills most rapidly. “When we omitted these motor abilities, our model no longer fit the ranking data,” Schneider says. “So we said, okay, we have to keep that in our model.” In other words, over the five years of the study, the kids who were better all-around athletes were better at acquiring tennis-specific skills.”

In fact, in general, whether you’re looking at swimmers, triathletes, or piano players, studies report that the amount of variance accounted for by “practice hours” differences is generally low to moderate.

“In a study that K. Anders Ericsson himself coauthored of darts players, for example, only 28 percent of the variance in performance between players was accounted for after fifteen years of practice.”

Gobet looked at chess players, and the hours they played before becoming masters.

“One player in the study reached master level in just 3,000 hours of practice, while another player needed 23,000 hours. If one year generally equates to 1,000 hours of deliberate practice, then that’s a difference of two decades of practice to reach the same plane of expertise. “That was the most striking part of our results,” Gobet says. “That basically some people need to practice eight times more to reach the same level as someone else. And some people do that and still have not reached the same level.”* Several players in the study who started early in childhood had logged more than 25,000 hours of chess practice and study and had yet to achieve basic master status.”

Justin Durandt, manager of the Discovery High Performance Centre at the Sports Science Institute of South Africa, routinely tests teenagers for running speed as he scours the country for rugby talent.

“We’ve tested over ten thousand boys, and I’ve never seen a boy who was slow become fast.”

But what about Michael Jordan?

Surely an elite of elites - THE towering figure for basketball for a decade, but a whispered mediocrity at baseball - doesn’t his case study give the lie to these case studies?

Well, maybe. But I will marshal 3 facts in defense of innate talent.

When MJ started playing baseball, he was already 31, which is quite old to try to adopt a new sport, with entirely new visual and physical schemas, particularly at the elite level. Our “never seen ice” examples were early 20’s.

Baseball in particular is more than usually dependent on acute eyesight - MLB players *average* 20/11 eyesight. That is roughly 1-in-10k eyesight. This is because of the extraordinary eyesight and reaction speed needed to accurately gauge a pitch.5 Jordan by all accounts had sharp eyesight- but was it 1-in-10k sharp, at 31 years old? I actually couldn’t find any citations of his eyesight in any year, but it seems unlikely that he was that acute.

MJ only played baseball for 1 season. Even a lot of these “never seen ice/snow” case studies gave a year or a couple of years before they were actually winning medals.

What else?

I’ve made the main thrust of my argument now, so I’m just going to conclude with some of the remaining fun facts and anecdotes from Epstein’s The Sports Gene that were most interesting to me.

Fun facts

The childhood key to adult endurance greatness: Many elite endurance athletes have a history of walking / running / skiing to and from a school miles away, as well as a history of being born and training at altitude.6

Perhaps slightly contrary to the previous point, getting a lot of sport-specific training hours before puberty may impair adult performance - elites don’t double down until after 15 years old (but then surpass near-elites by age 18 in practice hours).7

Tiger Woods is the archetypical 10k hours story, right? He was holding a golf club before he was 1 years old! But did you know: “With Woods, one oft-omitted fact about his childhood is that, at six months old, when most infants are just beginning their struggle to stand, he could balance on his father Earl’s palm as Earl walked around the house.” He probably could have been elite at many sports.

Usain Bolt and Veronica Campbell-Brown hail from Trelawney in Jamaica, which has an impossibly epic origin story.8

Jim Ryun, the first high school runner to break the 4, progressed in just 6 months from a 5:38 mile to a 4:21. He then “got serious,” broke the 4 as a high school junior, and 2 years later turned in a world record, then beat that world record the next year, hitting 3:51.1 on a cinder track with no rabbit.

Myostatin mutations, the ones that make bully whippets and Belgian Blue bulls impossibly muscular, occur in some humans (VERY rarely - like “handful in 8B” rarely) and have essentially no health downside besides needing extra calories, which is not something I’d have expected in something as heavily conserved as myostatin.

There is a known single point SNP that increases hemoglobin from 20-65%9 and has positive health impact on both athletic performance and lifespan.

There’s a quite prevalent mutation that makes steroid doping tests powerless, by enhancing metabolization of testosterone and making T/E ratios not move even if doping - if you carry two copies of UGT2B17. About 7% of Europeans and 1% of East Asians have this.

Wearing 8 pounds around your waist burns 4% more energy while running - but moving that down to 4 pounds on each ankle cranks that up to 24%.10

Because of the above, skinnier legs and narrower (“Nilotic”) builds are a significant factor in “running economy,” or the amount of energy it takes to run a given distance at a given speed.

There’s been a step change in sled-dog racing - formerly, teams would sprint and rest in intervals, but the first guy to run the two big sled dog races back to back revolutionized all that, and now they just try to run slowly and consistently the whole way.11

Sled dogs eat 10k calories a day when racing, and can actually recover from exercise while still moving and running12 - unlike humans, who have to rest between exercise sessions to recover. I want some of those genes!

The ApoE4 variant is the primary risk factor for TBI and brain damage after concussions or head injury, and the football players and boxers with the worst symptoms are usually ApoE4.13

Although I think we all have to give some credit to Judith Rich Harris’ The Nurture Assumption (1998) (!) - amazingly prescient and a fine work of scholarship for the time.

Gladwell is not the actual originator of the idea, K. Anders Ericsson is the one who actually studied skilled practice and expertise, and Gladwell basically unearthed a soundbite (10k hours) in his work, latched onto it, and memed it into the entire world’s heads.

Ericsson more or less disavows the entire 10k hours concept. I have his book Peak on my “to reread and review” list.

Even more funny - the original study Gladwell latched onto was data on only 10 violin players, relying entirely on years-later retrospective self-estimates of practice hours, and the violinists did “some of the restrospective estimates several times, and there was no perfect agreement” according to Ericsson himself. So more garbage quality than usual, even for the social sciences!

Not just that, but “10k hours” is totally fake. Practice hours before age 18 in the “elite” violin players was ~7400. By 20 it had gotten up to 10k, but even at 20, they weren’t anywhere near the top of their field, and were still learning - Ericsson points out that most elite musicians don’t peak until 30, or around 25k hours.

Male Olympic high jumpers typically average around 6’ 4.5” tall - in a sport that requires you to get your center of mass as high as possible, it’s a big advantage to start with a high center of mass.

Sadly, Australia has precipitously declined since that peak, to about half the medal incidence. The US has stayed right around .33, but Australia’s down to ~1.5 as of 2016 / 2020.

https://imgur.com/a/6nfngXS

“All this happens in the blink of an eye. (It takes 150 milliseconds just to execute a blink when a light is shined in your face.) But as quick as 200 milliseconds is, in the realm of 100-mph baseballs and 130-mph tennis serves, it is far too slow.A typical major league fastball travels around ten feet in just the 75 milliseconds that it takes for sensory cells in the retina simply to confirm that a baseball is in view and for information about the flight path and velocity of the ball to be relayed to the brain. The entire flight of the baseball from the pitcher’s hand to the plate takes just 400 milliseconds.”

“And because it takes half that time merely to initiate muscular action, a major league batter has to know where he is swinging shortly after the ball has left the pitcher’s hand, well before it’s even halfway to the plate. The window for actually making contact with the ball, when it is in reach of the bat, is 5 milliseconds, and because the angular position of the ball relative to the hitter’s eye changes so rapidly as it gets closer to the plate, the advice to “keep your eye on the ball” is literally impossible”

“Altitude natives who are born and go through childhood at elevation tend to have proportionally larger lungs than sea-level natives, and large lungs have large surface areas that permit more oxygen to pass from the lungs into the blood. This cannot be the result of altitude ancestry that has altered genes over generations, because it occurs not only in natives of the Himalayas, but also among American children who do not have altitude ancestry but who grow up high in the Rockies. Once childhood is gone, though, so too is the chance for this adaptation. It is not genetic, but neither is it alterable after adolescence.”

“A 2011 study of 243 Danish athletes found that early specialization was either entirely unnecessary or actually detrimental to ultimate development. The athletes were divided into elites, who had competed at the top level in their field, like the Olympics, and lesser, near-elites. The study focused solely on “cgs sports”—sports measured in centimeters, grams, or seconds, like cycling, track and field, sailing, swimming, skiing, and weight lifting. Both elites and near-elites “sampled” a number of sports in childhood, but near-elites—the lesser of the two groups—could be identified by a certain quality indicative of early specialization: they practiced more than the elites by age fifteen. It was only after age fifteen that the elites accelerated their practice pace and by age eighteen had surpassed their near-elite peers in training hours. ”

“The oral history of northwest Jamaica tells that the fiercest slaves were brought here, first by the Spanish and eventually the British, because it is surrounded by cliffs and ocean and difficult to escape.”

In 1655, when the British came to forcibly take Jamaica from the Spanish, some of the more enterprising slaves took the opportunity to escape to the cave-riddled limestone cliffs of Cockpit Country near Trelawney.

Many of them were of the Coromantee warriors, from Ghana:

“whom one British governor in Jamaica called “born Heroes . . . implacably revengeful when ill-treated,” and “dangerous inmates of a West Indian plantation.” Another Brit, writing in the eighteenth century, said that these “Gold Coast Negroes” were distinguished by “firmness both of body and mind; a ferociousness of disposition . . . an elevation of the soul which prompts them to enterprizes of difficulty and danger.”

From them, a leader arose named Captain Cudjoe. Despite being runaway slaves with no training or arms, arrayed against the British military at its peak, they were able to ambush and outfight enough soldiers coming in searching for runaway slaves, that they were able to arm and assemble a fighting force. The climax came in 1738, when they lured a contingent of British soldiers into a cave, sounded an alarum, and descended en masse to massacre them. According to the lore, they left one soldier alive to report back, “holding his ear in his hand.”

The British signed a treaty granting them Trelawney Town and freedom and autonomy a full 100 years before full emancipation of all Jamaican slaves. These are the ancestors of Bolt and Campbell-Brown.

Genetically though, nobody sees a real difference between Trelawney people and other Jamaicans. Still, fun story.

As seen in 7x Olympic medaler Eero Mäntyranta and his extended family, an adenine→guanine swap in one (but not both) of the EPO receptor genes, which stops the receptor construction about 85% of the way through and makes the receptor respond maximally to even minimal bloodstream EPO. The family members carrying the mutation actually have longer lives than the ones without.

“A separate research team calculated that adding just one tenth of one pound to the ankle increases oxygen consumption during running by about 1 percent. (Engineers at Adidas replicated that finding in the process of constructing lighter shoes.)”

This is Lance Mackey, who bred eager and high endurance but slow dogs, and won the 1000+ mile Iditarod and Yukon Quest races back to back in 2007 and 2008.

“As in humans, when sled dogs start training, they deplete the energy reserves in their muscles, undergo an increase in stress hormones, and damage cells. Human athletes experience this as fatigue and soreness, and must rest to allow the body to adapt to the exercise before coming back to training or racing. But the best sled dogs adapt on the run. Whereas humans have to alternate exercise and rest to get fit, premier Alaskan huskies get fit while barely stopping to recuperate. They are the ultimate training responders.”

If you dig into it, it’s about what you’d expect - the usual antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and IGF-1 factors that come on after exercise for most dogs / humans come on even under load for sled dogs. They also have tons of mitochondria and enhanced fat metabolization.

Which really makes you think - if we can just turn those on under load with no real downsides (except maybe needing more calories), that’s yet *another* total slam dunk as a gengineering target.

The other risk factors are age and number / severity of head blows.

"Carriers of ApoE4 gene variants who hit their heads in car accidents, for example, have longer comas, more bruising and bleeding in the brain, more postinjury seizures, less success with rehabilitation, and are more likely to suffer permanent damage or to die”

If you dig into more recent meta analyses to see if the trend held up, studies have been finding hazard ratios of ~1.4 for adults for the last 10 years at least for adults with one variant, and one had a ~2.4 HR for kids with at least one ApoE4 variant. It’s worse if you have two variants, which is ~2% incidence.