I’ve been on a bit of an “alien minds” theme lately (for inscrutable, some might say…alien reasons), and recently read a couple of books featuring “Rationalist Spirit Animal” John von Neumann, either wholly or in part.1

Since he’s one of the more fun examples of an alien mind in our past, and a frequent Rationalist shibboleth / hero, I thought I’d throw together a quick post on the fun von Neumann anecdotes I liked.

Why is von Neumann so famous? Here’s just a handful of stuff he did:

Father of Game Theory

Formulator of the “Hilbert Space” framework for quantum mechanics

Father of many computers, in both theory and practice (von Neumann architecture, the basis of all computing today? That’s him. So is MANIAC and various other early computers)

Father of cellular automata

One of the fathers and significant contributors to the H bomb

But aside from all THAT, the reason he’s the Rationalist Spirit Animal is that he worked with and around the smartest people in the world for his entire life (the Manhattan project, the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study, the RAND corporation, a whole suite of Nobel prize winers), and pretty much every single one of those people unanimously regarded him as the smartest person they’d ever met.

Birth of a giant

John von Neumann - nee Jancsi von Neumann (and known as Johnny in America) - was a Jewish Hungarian child prodigy who at six years old could divide two eight-digit numbers in his head and converse in Ancient Greek.

He grew up studying at least 7 languages, and could speak that many as an adult. By the time he was 8 years old, von Neumann was versed in both differential and integral calculus (aka Calc 1 and 2).

In High School, he was tutored with the other “Martians,” the coterie of Hungarian geniuses who later fueled much of the next 30 years’ progress in science and mathematics, as well as the Manhattan Project. The most influential professor and mentor at this school was Laszlo Ratz, who was the math professor, and specifically tutored Johnny.

His childhood friend Eugene Wigner pondering retrospectively about Ratz and von Neumann:

“He was just a startling 10-year-old boy, working next to 20 other bright 10-year-olds. Who could know that this precocious 10-year-old would someday become a great mathematician? Somehow Rátz knew. And he discovered it very quickly.”

Later, George Pólya, whose lectures at ETH Zurich von Neumann attended as a student, said, "Johnny was the only student I was ever afraid of. If in the course of a lecture I stated an unsolved problem, the chances were he'd come to me at the end of the lecture with the complete solution scribbled on a slip of paper."

PhD thesis

The only question von Neumann had to answer at his Phd thesis defense, posed by no less a formidable mathematical authority and grandee than Hilbert himself:

‘In all my years I have never seen such beautiful evening clothes: pray, who is the candidate’s tailor?’

There was no question that he deserved his Phd - he had resolved Russell’s Paradox with an axiomitization of set theory at age 19.

The human computer

Johnny went all in on computers, and they were extremely limited resources with much competition for the precious clock cycles.

As part of his jockeying for more computing time for his own projects, he ended up talking to a different team that wanted to book time, and rather than allocate precious computing time to them, he simply solved their problem in his head, on the spot.

“After listening to the scientists expound, Von Neumann broke in: ‘Well, gentlemen, suppose you tell me exactly what the problem is?’

For the next two hours the men at Rand lectured, scribbled on blackboards, and brought charts and tables back and forth. Von Neumann sat with his head buried in his hands. When the presentation was completed, he scribbled on a pad, stared so blankly that a Rand scientist later said he looked as if ‘his mind had slipped his face out of gear,’ then said, ‘Gentlemen, you do not need the computer. I have the answer.’

While the scientists sat in stunned silence, Von Neumann reeled off the various steps which would provide the solution to the problem. Having risen to this routine challenge, Von Neumann followed up with a routine suggestion: ‘Let’s go to lunch.’”

This sort of thing happened more than once:

“When George Dantzig brought von Neumann an unsolved problem in linear programming "as I would to an ordinary mortal", on which there had been no published literature, he was astonished when von Neumann said "Oh, that!", before offhandedly giving a lecture of over an hour, explaining how to solve the problem using the hitherto unconceived theory of duality.”

A common brain teaser that was going around the scientist circuit at the Princeton IAS:

In this puzzle, two bicycles begin 20 miles apart, and each travels toward the other at 10 miles per hour until they collide; meanwhile, a fly travels continuously back and forth between the bicycles at 15 miles per hour until it is squashed in the collision.

The questioner asks how far the fly traveled in total; the "trick" for a quick answer is to realize that the fly's individual transits do not matter, only that it has been traveling at 15 miles per hour for one hour.

As Eugene Wigner tells it, Max Born posed the riddle to von Neumann. The other scientists to whom he had posed it had laboriously computed the distance, so when von Neumann was immediately ready with the correct answer of 15 miles, Born observed that he must have guessed the trick. "What trick?" von Neumann replied. "All I did was sum the geometric series.”

The reference class for “smart”

You know how we keep mentioning Eugene Wigner? He comes up a lot in Johnny anecdotes, and it’s for a reason - he was his childhood friend, and he worked with him at the Princeton IAS and on the Manhattan Project and at Los Alamos.

But to give you an idea of how smart Wigner is, let’s look at his awards and accomplishments real fast:

I literally had to zoom my computer out twice to fit his list of “known for’s,” and you can see he’s won the Nobel Prize, as well as the Presidential Medal for Merit, the Franklin, Fermi, Einstein and Planck awards, AND had an award named after himself.

So keep in mind, THIS is how smart the guy saying this stuff about John von Neumann is!

Wigner:

“I have known a great many intelligent people in my life. I knew Max Planck, Max von Laue, and Werner Heisenberg. Paul Dirac was my brother-in-law; Leo Szilard and Edward Teller have been among my closest friends; and Albert Einstein was a good friend, too. And I have known many of the brightest younger scientists. But none of them had a mind as quick and acute as Jancsi von Neumann. I have often remarked this in the presence of those men, and no one ever disputed me.”

There’s a famous quote from Enrico Fermi to his doctoral student Herbert Anderson:

"You know, Herb, Johnny can do calculations in his head ten times as fast as I can! And I can do them ten times as fast as you can, Herb, so you can see how impressive Johnny is!"

Assorted plaudits

Edward Teller, inventor of Monte Carlo simulations, Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) in Bayesian methods, and Manhattan Project alum admitted that he "never could keep up with him"

Nobel Laureate Hans Bethe, originator of quantum electrodynamics and the proton-proton fusion model of how the sun works, and who published major papers every decade of his life into his 90’s(!) said: "I have sometimes wondered whether a brain like von Neumann's does not indicate a species superior to that of man"

Claude Shannon, inventor of information theory, binary, Boolean gates, cryptoanalysis, one time pads, and much more, called him "the smartest person I've ever met."

Eidetic memory

Von Neumann was also noted for his photographic memory.

Herman Goldstine:

One of his remarkable abilities was his power of absolute recall. As far as I could tell, von Neumann was able on once reading a book or article to quote it back verbatim; moreover, he could do it years later without hesitation. He could also translate it at no diminution in speed from its original language into English. On one occasion I tested his ability by asking him to tell me how A Tale of Two Cities started. Whereupon, without any pause, he immediately began to recite the first chapter and continued until asked to stop after about ten or fifteen minutes.

He famously memorized the pages of telephone directories, and entertained friends by asking them to randomly call out page numbers - he’d then recite names, addresses and numbers.

Once, he recited 50 lines of computer code from memory, and the program ran (as in, it had zero errors).

He proves what he wants

“Israel Halperin, von Neumann’s only doctoral student, called him a ‘magician’. ‘He took what was given and simply forced the conclusions logically out of it, whether it was algebra, geometry, or whatever,’ Halperin said. ‘He had some way of forcing out the results that made him different from the rest of the people.’

Hungarian mathematician Rózsa Péter’s assessment of his powers is more unsettling. ‘Other mathematicians prove what they can,’ she declared, ‘von Neumann proves what he wants.’

He wasn’t your typical nerd

Johnny wasn’t your typical uptight, risk averse, Aspie nerd - he was a hard partying, hard drinking social butterfly. He drove his cars too fast and wrecked them constantly, his house was a social nexus, and his wife was a fun drinker as well (and sharp enough that she in large part helped program one of the first computers).

“The marriage would nonetheless last until von Neumann’s death.

In Princeton, the couple settled into one of the grandest addresses in town. The white clapboard house at 26 Westcott Road would soon, with Klári’s help, become the setting for lavish parties that were soon the stuff of Princeton legend. Alcohol flowed freely, and von Neumann, who found chaos and noise conducive to good mathematics, would sometimes disappear upstairs, cocktail in hand, to scribble down some elegant proof or other.”

He was also, obviously, a bit of a gourmand, considering his rather rotund phenotype in a time when this was fairly rare.

He was famously well-liked, and had a stock of jokes that he would resort to whenever somebody asked him his opinion on some divisive political matter, and by all accounts had better social skills than most (certainly better than most in his mileiu).

From Enrico Fermi’s wife, Laura:

“Not only was he the ‘most normal’ of Hungarian scientists, in the opinion of his non-Hungarian friends, but he was also one of the very few men about whom I have not heard a single critical remark. It is astonishing that so much equanimity and so much intelligence could be concentrated in a man of no extraordinary appearance, short, with a round face and a round body. His qualities of genius include a prodigious mental speed and an enormous depth and adaptability of thought.”

And an even more humanizing anecdote - a bawd and a jokester:

“As if to offset his intellectual prowess, von Neumann was a fan of children’s games and toys, a hard-drinking party animal, and an inveterate jokester who loved to collect limericks. He quoted one of his favorite rhymes in a letter to his wife, Klara:

There was a young lady from Lynn

Who thought that to love was a sin.

But when she was tight

It seemed quite alright,

So everyone filled her with gin!”

This does rather argue that he’d make a better Post-Rationalist Spirit Animal, and it seems that this aspect of his personality is a bit neglected in the usual veneration of him.

But honestly, that makes me like him even more! He’s my kind of nerd!

RAND Institute

In keeping with the theme of “fun, fast driving, party animal nerds,” the founder of RAND corporation, John Williams, was another cast from that same mold.

He had such appreciation for von Neumann’s abilities that he paid him a full monthly salary, nominatively to only spend “the time he spent shaving” thinking about RAND problems.

“Rotund, weighing close to 300 pounds, Williams enjoyed the good life. He had RAND’s machinists fit a Cadillac supercharger to the engine of his brown Jaguar, taking it out for midnight runs down the Pacific Coast Highway at more than 150 miles per hour. At his house in Pacific Palisades, the booze flowed so freely that his erudite guests would be rolling around on the floor drunk by the end of his parties. If that all sounds rather familiar, it is no coincidence. Williams had attended von Neumann’s lectures at Princeton and worshipped him. Von Neumann’s spirit suffused RAND from its inception. All that was missing was the great man himself. On 16 December 1947, Williams wrote to his old professor.”

“For his services, von Neumann would receive US$200 a month – the average monthly salary at that time. The offer from Williams came with a charming stipulation: ‘the only part of your thinking time we’d like to bid for systematically is that which you spend shaving: we’d like you to pass on to us any ideas that come to you while so engaged’.”

As befits a “work hard, play hard” culture, the folks at RAND used to get rollicking drunk and try to trip each other up with brain teasers. It didn’t work on Johnny.

“Von Neumann began consulting for RAND the following year, holding court there much as he did at Los Alamos and Princeton. As he ambled through the criss-crossing corridors, people would call him aside to pick his brains about this or that. Williams would throw demanding maths problems at his hero in an effort to trip him up. He never succeeded. At one of his ‘high-proof, high-I.Q. parties’ one analyst produced a fat cylindrical ‘coin’ that was something of a RAND obsession at the time. Milled by the RAND machine shop at the behest of Williams, their proportions were carefully chosen so that the chances of falling heads, tails or on its side were equal. Without blinking an eye, von Neumann correctly stated the coin’s dimensions.”

Death

Likely due to his Manhattan Project and H-Bomb work, von Neumann was diagnosed with cancer quite young, in 1955, and in the midst of frenetic work going back and forth between RAND, Los Alamos, and Princeton, while consulting often for the government and serving on the Atomic Energy Commission. He died at age 53 after spending 11 months in the hospital.

While dying, he took up the lapsed Catholicism he had adopted when young and in Hungary to try to avoid issues with his family being Jewish, deliberately framing it as a Pascal’s Wager.

“There probably is a God. Many things are easier to explain if there is than if there isn’t.” (a line written to his mother earlier in life)

It was a source of consternation and morbid jokes, in turn, amongst his long-time friends.

Neurology quote

Not really related in terms of being a testament to his terrifying competence and smarts, but I found this quote from von Neumann an irresistable analogy:

“To understand the brain with neurological methods,’ he says dismissively, seems to me about as hopeful as to want to understand the ENIAC with no instrument at one’s disposal that is smaller than about 2 feet across its critical organs, with no methods of intervention more delicate than playing with a fire hose (although one might fill it with kerosene or nitroglycerine instead of water) or dropping cobblestones into the circuit.”

Encomium

One last remark from Edward Teller, who observed "von Neumann would carry on a conversation with my 3-year-old son, and the two of them would talk as equals, and I sometimes wondered if he used the same principle when he talked to the rest of us."

Ananyo Bhattacharya’s The Man From the Future, biography of von Neumann, 8/10, do recommend.

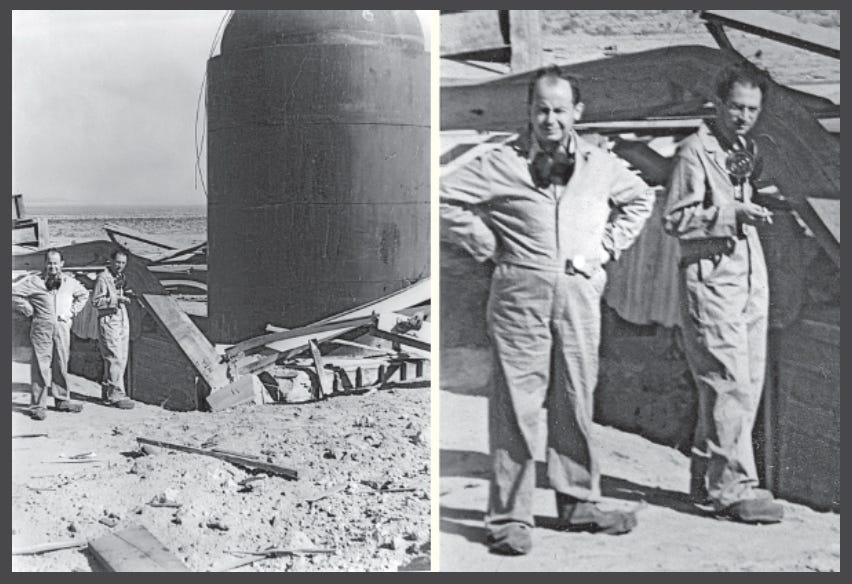

The Hargittai’s Wisdom of the Martians of Science, 2/10, do not recommend, but lots of fun / interesting pictures

Nothing to do with von Neumann, octopuses, or Oliver Burkewell, but if you want a REAL “alien minds” book, read the strange post-human vignettes in Fragnemt [sic] by ctrlcreep

Much of the lore about Johnny von Neumann is folklore, embellished beyond belief. Not that he wasn't a genius -- he was -- but he was human too. (The notion that the several world-class geniuses in his graduating class were all aliens from Mars was a joke. (I think.)) He had his limitations. The von Neumann architecture for computers, for example, is stolen valor. He did not come up with that architecture, but merely formalized and documented it.

Johnny von Neumann was staggeringly brilliant, though, no question about it. He did not win a Nobel prize, but he was of that class. And there is no one I can think of who is even comparable to him. People like him, and like Werner von Braun, seem to have disappeared from the earth. We just don't see their likes any more.

What made Johnny von Neumann who he was? Genetics seems to have made a contribution, as most of these Hungarians were Jews. Something in the environment? In the schooling they received? Historical and societal influences? I can't think of any other factors, but I can't tie them together into any sort of hypothesis, let alone find any proof to support it.

From the subtitle, I expected a misapplication of John Von Neumann. Rationalism isn’t correct, he is second to Gödel in being Godelian, as he was a day or so behind at breaking mathematics in their impromptu race. I view him like a reverse-engineer on the very idea of rationalism, taking it part, putting it back together again — an utter maniac. Thank god he was the father of computer engineering.

I am also surprised that his pro-Germanism wasn’t mentioned though, because there’re anecdotes on him playing extremely loud German music in and leading up to WW2 throughout Princeton annoying Einstein like crazy. This is despite the fact that he moved to the United States ahead of many because of the growing Nazi repression at Gottingen soon after Gödel got beaten up by a mob.

(Also Eugene Wigner’s biography is a treat, the man truly loved Wisconsin.)